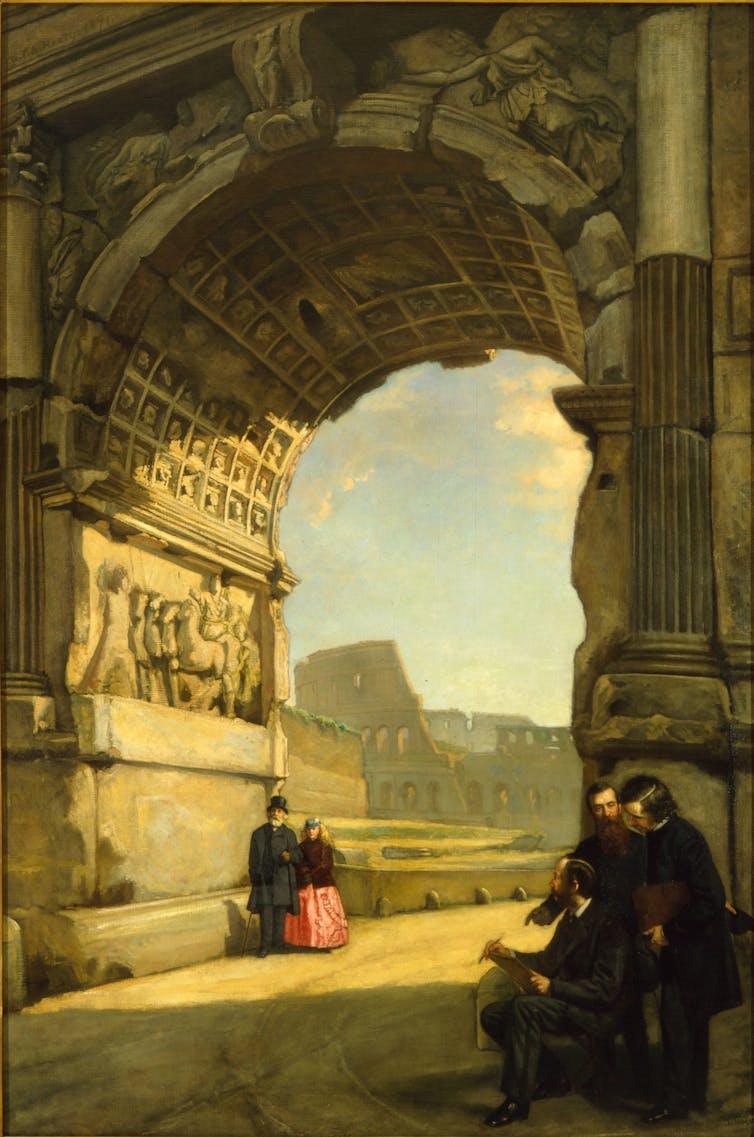

The ancient world of the Mediterranean has long permeated American society, in everything from museum collections to home furnishings. The design of the nation’s public monuments, buildings and universities, as well as its legal system and form of government, show the enduring influence of Mediterranean antiquity on American culture.

Until the late 19th century, Americans encountered the ancient world almost exclusively through reproductions – in books, artwork and even popular plays. Very few could afford to travel abroad to encounter Mediterranean artifacts firsthand.

Yet despite barriers to access, many Americans forged personal connections with the cultures of the ancient Mediterranean – not only the Greeks and Romans, but also the Egyptians and Israelites. Perhaps the newness of American culture inspired this deep interest in the ancient past.

One of the most fascinating aspects of Mediterranean antiquity’s influence on America, even before it officially became a country, is how it cut across cultural lines of race, class and gender. Far from being the preserve of a privileged few, the art and literature of the ancients was often embraced by Americans of all stripes – including the enslaved Black poet Phillis Wheatley (circa 1753-1784) and Black and Native American sculptor Edmonia Lewis (1844-1907). But the circumstances of these encounters and the way individual Americans thought about antiquity varied greatly.

I’m an art historian specializing in ancient Mediterranean art and culture. I am particularly fascinated by the way Americans, from the earliest days, made creative connections between past and present, despite being separated by thousands of miles and millennia of history.

In researching and selecting works of art for the exhibit “Antiquity and America,” on view at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, I was excited to show an exceptionally diverse range of American encounters with the ancient world, especially in portrait painting.

Marker of education

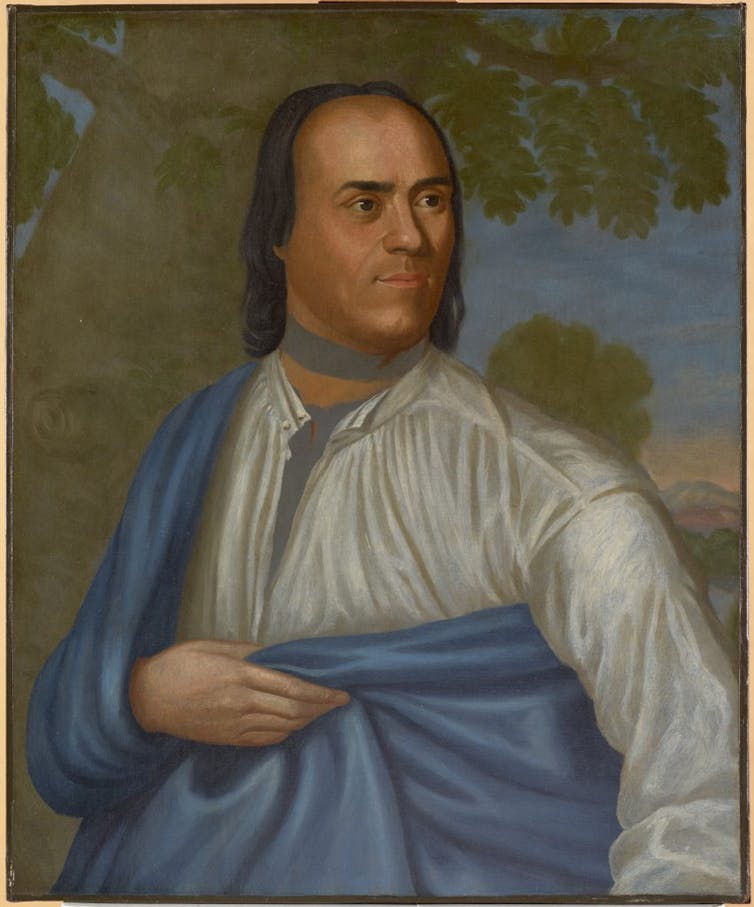

Take, for example, Samson Occom (1723-1792), a member of the Mohegan nation, Presbyterian minister and one of the first Native Americans to pen an autobiography in English.

His unfinished portrait, painted by Nathaniel Smibert (1735-1756) in the mid-18th century, alluded to Occom’s Indigenous identity in the coloring of his skin and the styling of his hair. Simultaneously, it also referenced his training in classical literature and oratory, acquired by studying with Eleazar Wheelock (1711-1779), a Connecticut Congregational minister.

Occom’s pose and draped cloak recall those found on ancient statues of Roman senators – a portrait convention familiar in early America from prints circulating at the time – and one that would later become quite popular in American society.

While his learning in Greek and Latin was undoubtedly a source of great pride for Occom – and a way for him to level the playing field with the European colonists – it was used by others to demonstrate the “civilizing” effect of European culture and education in the British Colonies.

In 1776, Eleazar Wheelock sent his former pupil Occom to Great Britain to raise money for a Native American school – funds that were ultimately repurposed for the founding of Dartmouth College. Occom would later charge Wheelock with using him as a “gazing stock” in Europe while planning all the while to use the funds for the benefit of white settlers.

Shaping public opinion

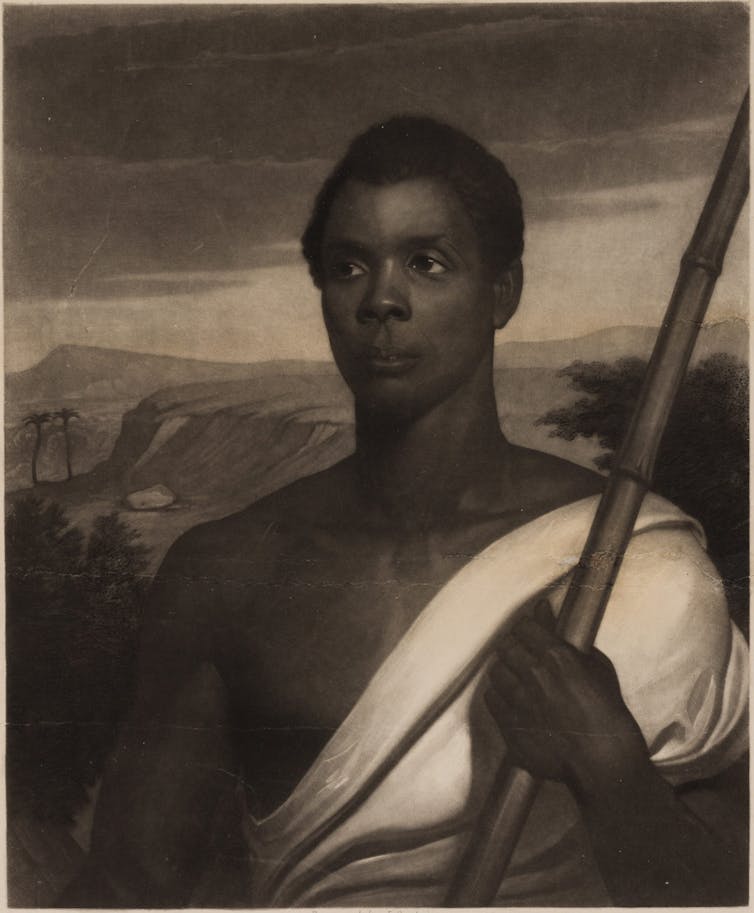

A portrait of Sengbe Pieh, also known as Cinqué, who led the 1839 Amistad slave ship revolt, is an example of Black Americans’ use of the classical world for political purposes.

Commissioned by Robert Purvis (1810-1898), a Black Philadelphian and prominent abolitionist, this striking portrait by John Sartain (1808-1897) was intended to shape the popular image of Pieh and his fellow Africans during their Supreme Court trial for mutiny and murder in 1840-1841.

Pieh’s African identity is made evident not only in the tone of his skin, but in the bamboo staff he holds and the landscape in background depicting his homeland. The white cloak draped over his shoulder would have called to mind the white robes worn by Roman senators and, by extension, the Roman virtues of honor and dignity.

Pieh and his fellow Africans were ultimately acquitted and returned to the Sierra Leone Colony in 1842.

Feminist icon

Caroline Sanders Truax (1870–1940), one of the first women admitted to the New York state bar, was so enamored by the ancient past she was portrayed as the Greek lyric poet Sappho by painter Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904).

This was a bold choice for a representation of an American woman in 1899. Sappho, whose writing is among the only surviving sources of female authorship from antiquity, was already an icon of the first-wave feminist movement, and the homoerotic themes of her poetry were well understood. Was the choice the artist’s – or the sitter’s? The most likely answer is it was by mutual agreement, perhaps inspired by Truax’s knowledge of classical language and literature – and her own interest in composing lyric poetry.

The portrait was a sensation in New York society when it arrived from the artist’s studio in Paris. It was featured in several portrait exhibitions and newspaper articles – and was hung with pride by Truax and her husband in their home.

For generations of Americans, the history and literature of Mediterranean antiquity was fertile ground for contemporary comparisons. It was universal enough to be brought into debates about the Constitution and founding principles of democracy, slavery and abolition, and women’s rights and suffrage. It was also of great individual significance for Americans of many different backgrounds – a past they were on intimate terms with, despite the millennia and miles separating the United States from the ancient Mediterranean.

Sean Burrus previously worked for the Bowdoin College Museum of Art. He received funding from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.