In 2018, USA Today named Electronic Arts the fifth-most hated company in America, which was actually an improvement from when The Consumerist awarded them the gold medal two years in a row. The case wrote itself: EA shutters once-profitable studios, aggressively pushes obnoxious loot boxes, and has long forced crunch on developers, among other sins.

Perhaps the most common complaint is that EA fails to innovate. Fans and critics have called out their overpriced Sims 4 content packs, the laziness of their yearly sports titles, and their undercooked sequels to legacy franchises. But it wasn’t always this way. In 2008, EA took a genuine creative risk on two new franchises… and was punished for it.

One newcomer was Dead Space. Pitched as Resident Evil 4 meets Event Horizon, it had fresh ideas but was easy to pick up and understand. A spaceship was overrun by monsters, and you had to dismember them. But Mirror’s Edge, which parkoured onto PCs 15 years ago, was a little trickier to grasp.

Developed by Swedish studio DICE, which wanted to grow beyond its reputation as a Battlefield factory, Mirror’s Edge looks like a first-person shooter but places its emphasis on movement. You run, jump, and otherwise do everything possible to avoid the guns that other games would shove in your hands 30 seconds after you hit start.

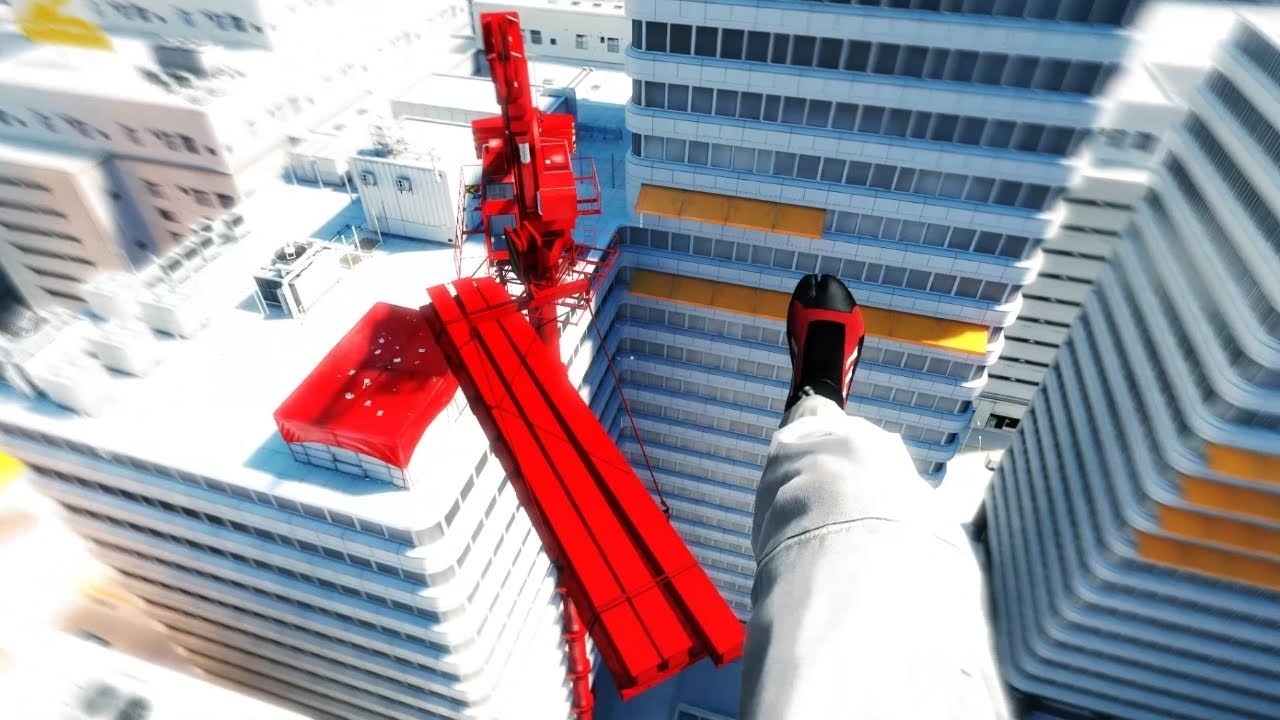

The game’s unique color palette gives it a striking first impression. Set among the hallways and rooftops of a vaguely futuristic city, heroine Faith Connors navigates stark white urbanity slashed through with streaks of red, yellow, and green. It’s a stark contrast to the taupe rainbow that the Gears series had made a generational standard, and it helps Mirror’s Edge continue to punch above its graphical weight.

There may be green, but there’s no greenery, as the unnamed city is a sterile corporate paradise. Essentially a cozy dystopia, every need is met if you work hard and don’t ask questions. Faith plays the rather literal role of runner, a sneaker net courier for illicit information. In gameplay terms, you’ll use a parkour toolbox of sprinting, jumping, wall-running, and somersaulting to navigate rooftops and dodge authorities. Sometimes you need to quickly string together moves to outrun cops, while elsewhere you’ll puzzle out how to clamber up a seemingly inaccessible elevator shaft or construction site.

It’s a clever inversion of what’s expected from a first-person game. The environment, rather than being a backdrop to the gameplay, is the gameplay, both an obstacle and your only ally in avoiding bullets. You can wield the guns enemies drop (a likely concession to EA’s marketing department), but they slow Faith to a crawl and quickly run dry, making them disposable bursts of power. Gaming instincts may draw you to them, but you’ll soon learn that it’s far more fun to ignore firearms in favor of parkouring past an enemy… or parkouring your legs into their face.

“Masterpiece” and “genre-defining” were thrown around in reviews, but so were “frustrating” and “unforgiving.” It’s hardly above criticism, but it’s clear many players didn’t get what Mirror’s Edge was going for, in part because its target was unique. It may have looked like a novel shooter, but it was really a radical reinvention of the platformer, with a heroine who could splatter on the sidewalk after one wrong move.

Sure, it’s short, its central political conspiracy meanders, and the combat is brutally unforgiving until you grasp its quirks. But when your vision blurs as you string together a flawless run under a crisp blue sky, Mirror’s Edge feels joyful in a way few games ever have. It’s so committed to its perspective that there isn’t even a status bar. It’s just you and the city, to navigate as you see fit.

Unfortunately, fawning retrospectives don’t retroactively move units, and EA found itself with an acclaimed sales flop. Dead Space, while underperforming, at least made money; Mirror’s Edge lost it. In 2010, EA President Frank Gibeau spoke with Develop Online about what the company had learned, and looking back makes you want to reach through the years, grab his shoulders, and beg him to concoct better takeaways. Did Mirror’s Edge need a better learning curve? Sure, that’s fair. Did it have to “execute”? We’re not sure what that means. Did it need multiplayer and online components? No, Frank. No!

Dead Space 3 would see multiplayer shoehorned in at EA’s behest, and the only thing it executed was developer Visceral Games. In trying to appeal to a broader audience, EA lost the audience it had. 2016’s Mirror’s Edge Catalyst, a misunderstood “preboot,” was spared the worst of EA’s meddling, but you have to turn off all the handholding before it matches the thrills of its predecessor. It also struggled to find an audience, likely grounding the franchise for good.

EA is in business to make money, so you can’t blame them for chasing it. But the real lesson EA learned was that innovation isn’t worth the hassle. Mirror’s Edge worked because, for good and ill, it was uncompromising. It felt totally disinterested in chasing trends and padding itself with busywork, which is admirable but not marketable.

You can see the influence of Mirror’s Edge in games like Dying Light, which stapled its parkour movement onto a zombie apocalypse and sold millions. EA probably wishes that’s what DICE had dreamed up in the first place. But Mirror’s Edge is singular in a way few titles have ever been. Gamers may hate EA, but the company deserves a little credit for the time it let DICE stretch its legs.