When the iPhone launched on June 29, 2007, it did so without any third-party apps, much to the chagrin of its customers and the skeptical tech press. The original iPhone only had 15 native apps, and users wanted more.

Apple encouraged iPhone users to use “web apps” with limited features in place of the native apps that existed on other mobile platforms of the era, including Palm, Windows Mobile, and BlackBerry. Users and developers were undeterred. In just over a month, not only was the iPhone “jailbroken” (a term meaning unauthorized software can be installed, manufacturer policies be damned), but the first third-party game was released for the burgeoning smartphone.

By the time Apple announced the iPhone software developer kit (SDK) in March of 2008, interest in the groundbreaking smartphone had increased greatly and there was already a flourishing jailbreak community of app developers. This primed the pump for the launch of iPhone OS 2 in July 2008. Launched alongside the iPhone 3G, iPhone OS 2 brought a slew of new features, including support for Microsoft Exchange and Apple’s revamped cloud offering, MobileMe. However, the real star of the show was the App Store, the new centralized digital storefront where users could find and download apps — free or paid — for their iPhone or iPod touch (remember those?), right on their device.

It's not an exaggeration to say that within days, the mobile software industry, if not the software industry as a whole, completely changed.

Fifteen years later, the reverberations of that change are still being felt by developers, businesses, and users. Not only has the way we consume all apps — mobile or otherwise — changed to be more like the App Store, but an entire industry has been built around the broader App Store ecosystem. According to a study from the Analysis Group, the App Store ecosystem generated $1.1 trillion in total billings and sales in 2022. The report also states: "Users have downloaded apps more than 370 billion times and developers have earned more than $320 billion in earnings directly on the App Store since its launch."

How did we get here? And where does the App Store go in the future?

Late to the Party but Right on Time

Apple was not the first company to come up with the idea of an App Store. T-Mobile’s Sidekick, created by Danger (members of which would later go on to work on Android), was one of the first smartphones to have an integrated software catalog, all the way back in 2003. Before that, in the cell phone era of the late 1990s and early 2000s, users could buy ringtones or small web games from their Nokia 3310s or Samsung clamshells.

But just as the iPhone was a different type of device, unlike anything that had existed before it, apps for the touchscreen interface were different from anything we had ever seen before on a handheld.

Although relatively late to the concept of smartphone apps, the iPhone had some key advantages over its rivals and predecessors. First, the superior hardware that the iPhone (and iPhone 3G) had over its competitors meant that the apps could be higher quality than what was available on a BlackBerry or a Palm Treo. Importantly, Apple opted for a similar programming language and UI system that Mac OS X developers used. This meant that there was a built-in pool of thousands of Mac developers ready to build for the new platform, not to mention millions of would-be developers ready to dip their toes into creating mobile apps. The capacitive touchscreen, with its support for multi-touch gestures and the gyroscope for movement, enabled new game and app paradigms that simply hadn't existed.

Apps for the touchscreen interface were different from anything we had ever seen before on a handheld.

Second, was the timing. The summer of 2008, was an important moment in tech history. For the first time, internet apps and services were fast enough, and high-speed connectivity (via 3G or wireless networks) ubiquitous enough that you could deliver incredible experiences on a smartphone. This was when the world of Web 2.0 was hot, with startups and platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and WordPress rapidly disrupting and reshaping life at rapid speed. Even if Apple had been ready to launch the App Store in 2007, alongside that first iPhone, the software and tech ecosystem wouldn't have been able to support it.

This led to an explosion of mobile apps and games that could communicate with online services, offering users more connected experiences and real-time offerings. The graphical capabilities of the iPhone and iPod touch devices were also a significant improvement over other handheld devices of the era, opening up a new world for developers to get 3D games into the hands of a growing user base and kicking off a casual games market that only continues to grow today.

Third, and perhaps most crucially, was Apple’s commitment to controlling the ecosystem. Unlike app storefronts on other mobile (or even desktop) platforms, the App Store was built around Apple’s rules and regulations from the beginning. Carriers would be unable to dictate what could or could not be installed on the device; Apple would and could. That meant that all apps made available in the store had to be vetted by Apple first and follow specific guidelines for inclusion. It also meant that, jailbreaks aside, the only way to run a third-party app on an iPhone or iPod touch was through the App Store.

Apple’s approach here was much more akin to what Nintendo, Sony, and Microsoft did with their video game consoles and much less like the approach of Apple and Microsoft when it came to allowing software on Windows or the Mac. Not only would Apple control what was on the App Store, it would also facilitate all payments for apps, and take a 30 percent cut for its trouble. Still, developers could set their own prices for their apps, something not always possible on other platforms (if at all), and soon, it became clear that there was money to be made selling apps. Real money. Money that many of the developers in the store had never seen before or so quickly.

As apps became so ubiquitous, a new marketing slogan emerged: “There’s an app for that.”

From the beginning, some developers and users balked at these terms, taking exception to the size of Apple’s cut of the app price and the guidelines set by Apple around what could and could not be on the platform, as well as the App Store being the only sanctioned distribution method for getting apps on the device. These same tensions are still prevalent 15 years later, as seen in Epic’s lawsuit against Apple, and the various antitrust probes by the EU, the U.K., and the United States.

Still, Apple’s control of the overall ecosystem, the quality of the development tools, and the size of the user base that was double or tripling every single quarter encouraged developers to commit to the iPhone ecosystem, and users themselves got hooked. As apps became so ubiquitous, a new marketing slogan emerged: “There’s an app for that.”

App Overload

As of June 17, 2023 (the last time my Apple data archive was updated), I have downloaded 1,293 apps across iOS and tvOS over the span of just under 15 years. Now, part of that is a consequence of my previous jobs as an app reviewer and early adopter, but some of it is just due to me having spent 15 years in the iOS walled garden.

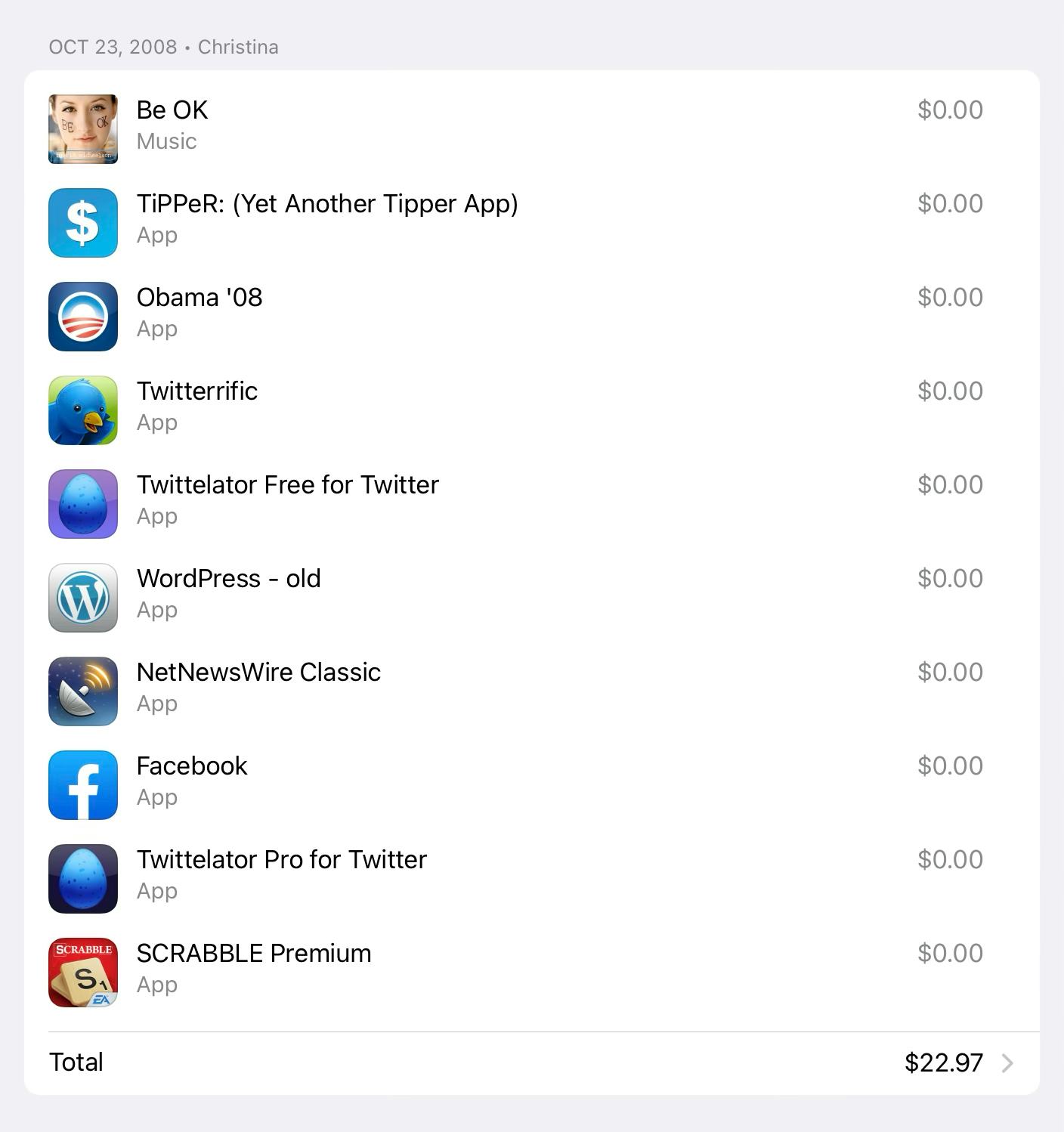

Looking through my decade and a half of App Store purchases is like looking through a time capsule of the last era of tech, seeing all the fads, the booms, and the busts of the era. The first app I ever downloaded was the official Obama app. My other first-day apps included two different Twitter clients, the official Facebook app, an RSS client, and an $8 copy of Scrabble. Today, the Facebook app is still active and amazingly, that old version of Scrabble still works.

It’s also a remnant of a time that has largely passed. Because even as App Store revenues continue to grow each and every quarter, lining Apple’s pockets to the tune of tens of billions a year, our cultural reliance on mobile apps themselves has changed.

Mobile or tablet apps are still necessary or ideal for streaming services such as Netflix or Spotify, games like Minecraft or Roblox, and photo or video apps like CapCut or Facetune, but other one-off apps are increasingly unnecessary and even superfluous.

Yes, I have an app for my bank, but I’m just as likely to visit its website when trying to check my balance. Whereas I used to get excited about a new app on my iPhone, I now often resent being asked to download an app when I know that the website will work just as well and cause fewer disruptions or take up less space on my phone. Apple introduced App Clips in iOS 14, which was supposed to solve this problem by letting users access a small portion of an app instead of downloading the whole thing for one-time use. But three years later, the feature has little user or developer adoption. I think I have seen App Clips exactly once in my various travels across the world — and that was through a place that also accepted payment via Apple Pay, negating the need for the App Clip at all.

Moreover, the business realities around mobile apps have changed along with the App Store. Apple still takes that 30 percent on sales, but that cut now includes in-app purchases and subscriptions. Subscriptions are increasingly becoming the way developers sell apps, in part because of how difficult Apple makes it for developers to sell upgrades. Unlike standalone software, a developer can’t easily offer a discount to existing users for a new version of an app. Instead of offering upgrades, developers are encouraged to design with subscriptions in mind, so that the apps get updated on a regular cadence or offer a regular allotment of services, rather than a one-off purchase. Apple didn’t invent the app subscription market; Adobe mainstreamed software as a service with Creative Cloud in 2013. But its pervasiveness on the App Store (a trend that has followed into web and desktop apps as well) has left many of us with app and subscription fatigue.

There is still a lot of money to make on mobile apps, but usually not just on the app itself. The most successful app developers today aren’t the same as they were 15 years ago, where a good novel idea could net millions of downloads overnight. Now, apps need to serve as part of an ongoing business and not necessarily be the business themselves.

The Future of the App Store

As a software developer, I think about what the next 15 years of mobile apps will look like. Will AR headsets replace our phones, where everything lives in the metaverse or Apple’s idea of Apple Vision Pro? Will the web have shown its ultimate dominance, eliminating the need for standalone apps at all? Will I be playing the 2038 equivalent of Gossip Harbor on a thin foldable slab of glass that looks like something out of Westworld?

One thing that might be different is that we might finally have more than one App Store. Under the EU’s new Digital Markets Act (DMA), Apple and other large tech companies are required to “allow third-parties to interoperate with [their] own services in specific situations.” Translation: apps can be installed through a storefront not controlled by Apple. Although the details of how this enforcement will play out are still unclear, reports suggest that Apple is preparing to allow alternative app stores on the iPhone, at least in the EU. The DMA deadline for companies to comply is March 2024, so we should see how Apple adapts to the new law soon. Similar bills requiring third-party app store and third-party payment processor options are under consideration in other countries as well. So in 2038, the App Store might still be the centralized place to get iOS apps, but it probably won’t be the only place.

One thing that might be different is that we might finally have more than one App Store.

An area that I hope will be different is the quality and discoverability of apps in the App Store. Early on, the control that Apple exerted over the App Store was a net positive to both Apple and its users; Apple touted that its rules of what could or could not exist helped protect users from malware, scams, and needlessly expensive apps. But 15 years later, many of those early promises have faded away, and the App Store is littered with scammy apps emboldened by fake reviews, and Apple has done little to stop the problem.

We are left in a situation where fly-by-night companies can make millions of dollars off of unsuspecting users, sometimes for apps that literally do nothing, but if a developer wants to make an open-source classic video game emulator, users have to jump through a bunch of convoluted hoops just to get it on their devices. Perhaps additional regulation — or maybe even AI — will help the process of filtering out the scam apps and fake reviews, leaving users with a better experience. That could even lead to an app resurgence, if done correctly.

I expect the proliferation of app subscriptions to continue, even as users complain and bemoan the practice, but it is equally possible that in another 15 years, a different revenue stream may have taken hold. Who knows, maybe micropayments will finally be a thing (I’m not holding my breath).

Still, I fully expect that an App Store will exist in some form and that Apple will do its damndest to get a percentage of every single app that I buy. Maybe that old version of Scrabble will even work.