A decade after it ended, Breaking Bad is remembered as one of the best TV shows ever made. Thanks to its impeccable writing, its experimental direction, and its towering central performances, the show has earned a legacy that has only grown thanks in large part to its time on Netflix. New viewers who find the show now can binge the entire thing, comfortable in the knowledge that everyone was happy with how things wrapped up.

When “Ozymandias” first aired, though, no one knew where Breaking Bad was going. They didn’t know that Jesse would be imprisoned by Nazis, or that Walt would spend a full year holed up in a cabin. It was “Ozymandias,” an episode that felt like a culmination of everything that had come before it, that pivoted Breaking Bad toward its endgame, and ultimately cemented the show’s legacy.

A decade later, the episode remains one of the more acclaimed hours of TV ever, and it’s also the one that fully confirmed that Breaking Bad was not going to fumble the ball on the one yard line. It was an episode so stellar that any doubt you might have had about whether the show would meet your expectations was squelched.

“Ozymandias” has often been described as the first series finale of Breaking Bad. It definitively concludes the main plotlines of the series, killing Hank and ending his quest to bring Walt to justice, and simultaneously ending Walt’s ability to retain his grasp on something resembling a normal life. By episode’s end, his only options are to go into hiding or get arrested, and he chooses to leave everything behind to evade authorities.

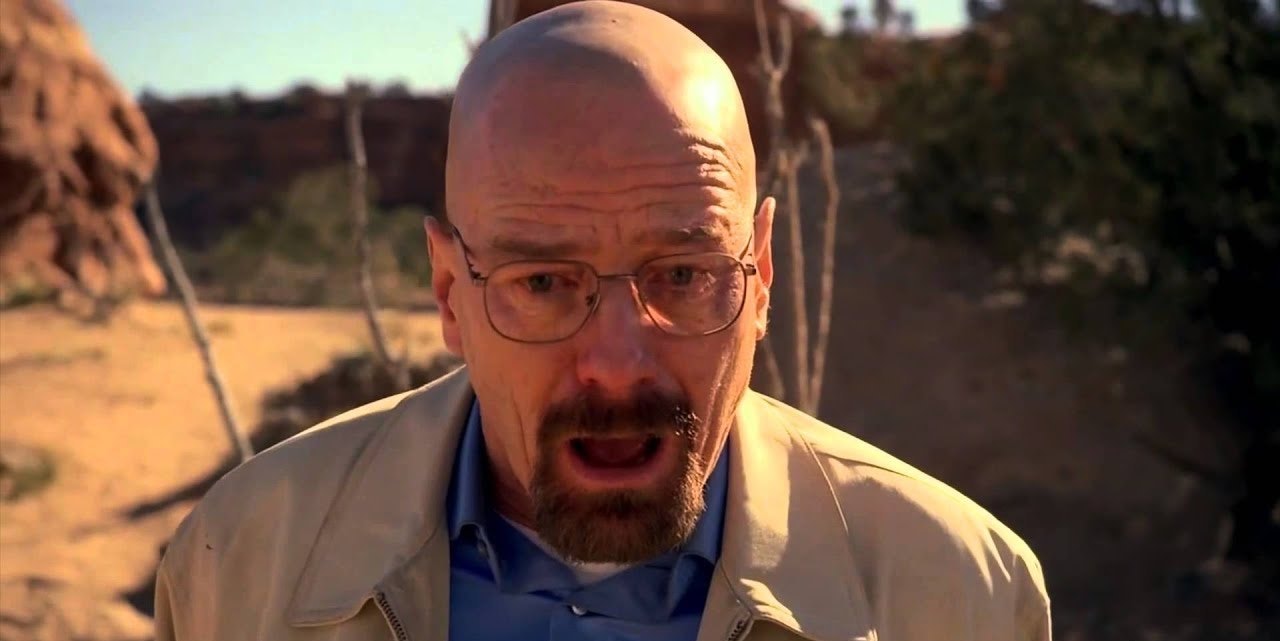

Before he makes that fateful choice, though, we get the pleasure of watching Walt’s entire life crumble to pieces around him. Like the character in the titular poem that the episode’s title is referencing, Walt has built an empire only to watch it crumble. Throughout the show’s entire run, Walt’s narcissism had blinded him to how his accumulation of power was always going to lead him here. He conquered worlds, only to watch everything he built disintegrate into dust.

Perhaps the greatest example of this comes with his family. When he tries to gather them so that they can leave with him, he discovers that they want nothing to do with him. In fact, he’s alienated them to such an extent that all they feel for him is fear. It’s a stunning moment, a total break, a realization that Walt has descended into such depths of darkness that his wife and son believe he’s directly responsible for Hank’s death. There’s a physical fight, but what’s devastating here are the emotional implications of this moment. Walt, who has built an entire meth empire and killed scores of people claiming that he was doing it for his family, has lost them.

The rest of the episode pivots on this sequence, as Walt kidnaps baby Holly before attempting to exonerate Skylar by suggesting that she never went along with what he was doing. It’s the one moment of nobility he gets in the whole episode, and one that reminds us of who he was when the show began. What’s more crucial about “Ozymandias,” though, is all the ways it lays bare who Walt really is.

He is focused entirely on himself, unable to grapple with how he’s treated those around him. He permanently severs his relationship with Jesse, the one person who could still redeem him, telling him that he watched Jane die, and letting the Nazis take him prisoner so that he can cook meth for them. In the episode’s final moments, all Walt has is his money, a giant barrel that he takes with him as he disappears into his new life. He’s lost everything except the one thing he cared for the most.

“Ozymandias” definitively showed that, regardless of how many fans may feel about Walt, the show knew he was deplorable. In building an entire episode around his downfall, and turning it into one of the show’s very best outings, Breaking Bad cemented the legacy it still holds a decade later. Whatever you think of the show’s actual finale (which maybe gives Walt a bit more redemption than he gets here), “Ozymandias” feels like a culmination all its own. In a way, everything that came afterwards was just a coda.