Are video games art? This question was never more annoying than in the aftermath of Roger Ebert’s provocative arguments to the contrary, after which many petulant responses helped make his point. Ebert claimed the fundamental limitations of the medium work against it: all games require at least some player agency, while films and novels have total authorial control.

It’s an idiosyncratic argument that relies on one’s personal interpretation of what art is, but you can see his point: you don’t need years of ingrained skill and knowledge to watch a good movie. An outraged internet demanded Ebert sit down and put a dozen hours into Shadow of the Colossus, but how do you appreciate its artistry if you don’t have the requisite background to get past the first boss? There’s nothing emotionally moving about a “Game Over” screen.

That, perhaps, is what made the 2013 release of The Stanley Parable so refreshing. While most of the titles shoved in Ebert’s face had a skill floor, were exhaustingly self-serious (Dear Esther), or both (Braid), The Stanley Parable was a playful, deceptively straightforward affair that rewarded experimentation rather than reflexes.

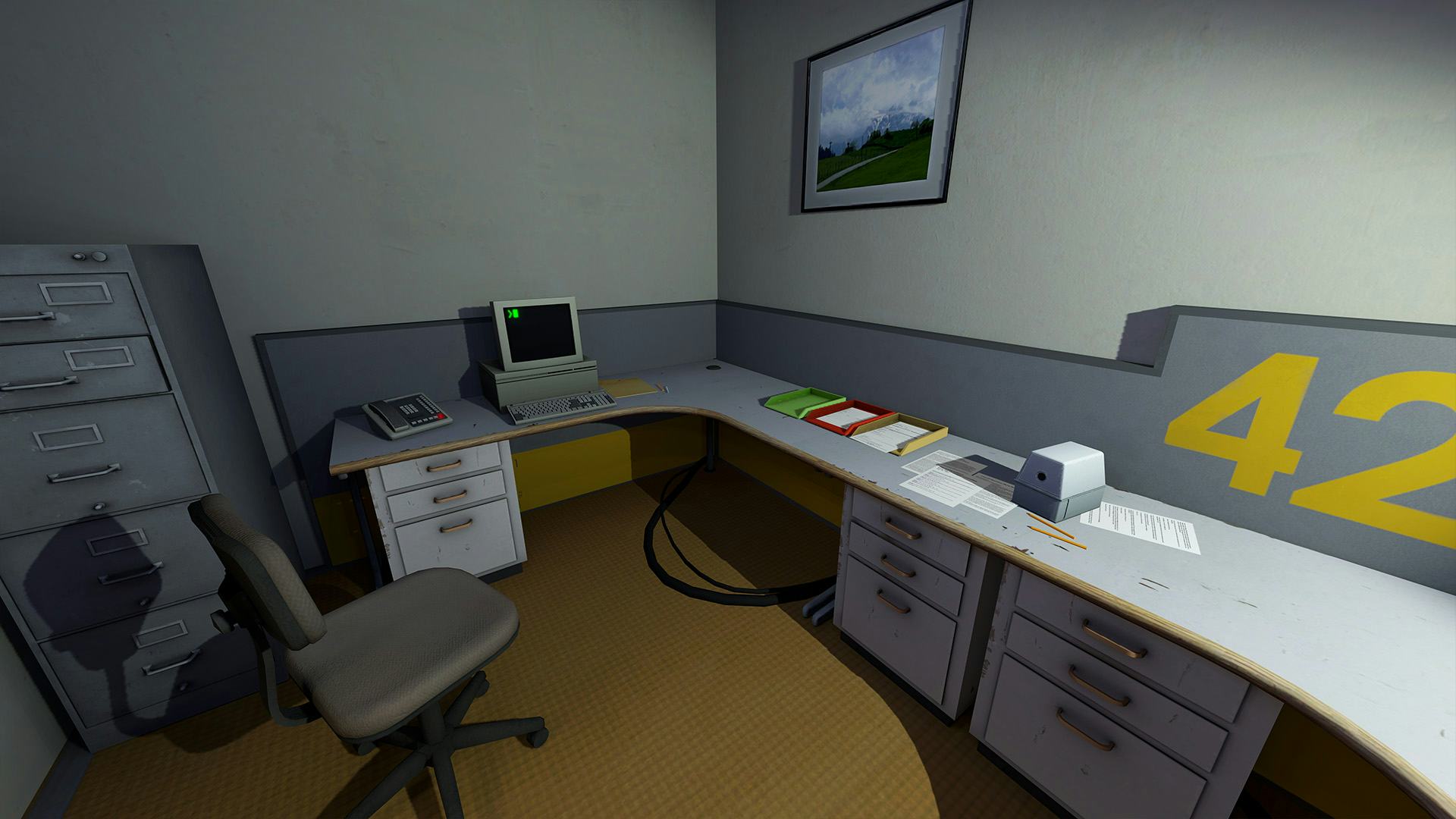

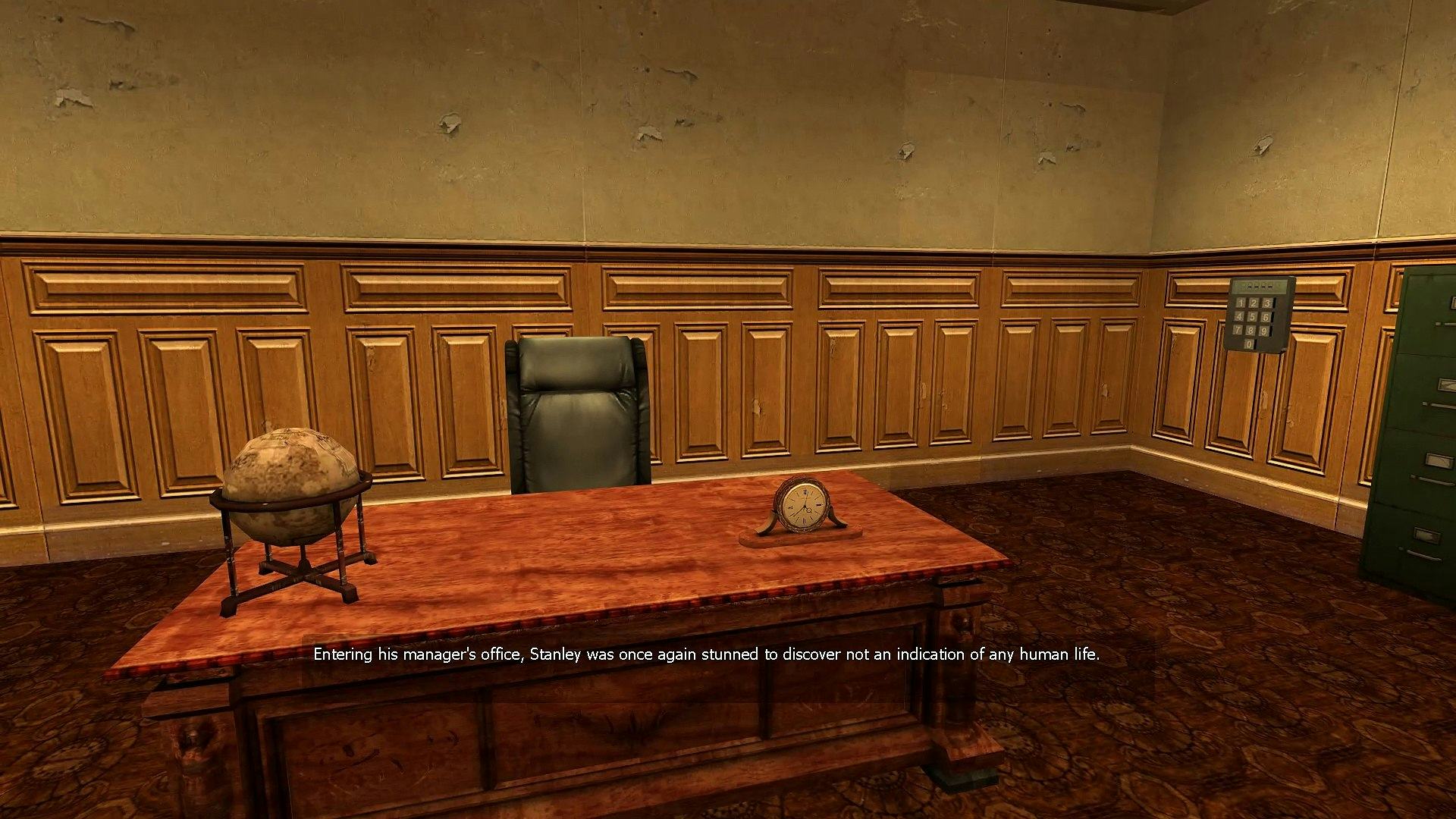

In it, the silent Stanley is introduced by the Narrator (Kevan Brighting) as a mundane man happy in his mind-numbing office job where he presses the buttons he’s told to press. But one day, there’s no work waiting for Stanley, and his office appears deserted. You set out to find answers, and within minutes, you enter a room with two doors. The Narrator says, “When Stanley came to a set of two open doors, he entered the door on his left,” and whether you do as he says informs the rest of your experience.

Obey the detached Narrator to the letter and you’ll get a quick, straightforward narrative about breaking free from an oppressive workplace. Enter the door on the right or disobey some of his other decrees, and the Narrator will begin commenting on your decisions. You can “finish” the game in 15 minutes, but the real fun comes from repeated playthroughs exploring all the permutations that can emerge from your first decision. Your choices can lead to 19 different endings, a wild variety in tones, and subtle changes in rooms you’ve sped through a dozen times before.

Without spoiling too much, you may find yourself standing in a broom closet for half an hour just to see what happens. You can uncover a museum dedicated to the game’s development, where learning what changes were made to avoid confusing players feels like a meta-commentary on the game’s premise. Another path leads you to the Narrator’s own horrendous attempt at an artsy game, which requires you to mash a button that emits an obnoxious buzzing sound for four hours before the gag concludes. Attempt to cheat, and you’ll be transported to the “serious room” for a stern lecture.

First released in 2011 as a Half-Life 2 mod, 22-year-old designer Davey Wreden became an overnight sensation after accruing 90,000 downloads and praise from publications like Wired and Ars Technica (the latter, as befitting the era, highlighted reader comments debating The Stanley Parable’s validity as an “art game”). Wreden then collaborated with designer William Pugh to release a polished and expanded standalone version in 2013, while a further-expanded “Ultra Deluxe” release hit virtual shelves last year.

It’s that middle edition that received the most attention. The Stanley Parable wasn’t an intentional response to Ebert’s comments, but its meditations on how choices form a relationship between developer and player certainly grapple with the objection he raised. The Narrator cajoles, begs, and threatens you in his attempts to get you back on track, and his musings on game design, agency, and life — mostly enjoyable, occasionally juvenile — are enhanced by Brighting’s dry wit and genuine emotion.

What’s most important, however, is The Stanley Parable’s joyful sense of discovery. Poking around rewards you with commentary on your thought process, which encourages you to make even stranger decisions. It’s a clever game, but you feel smart for playing it, as opposed to countless art games that feel like they’re trying to communicate their smartness at you. If you can think of something to do, whether it’s leaping from an elevator or lingering in a break room, odds are good that Wreden and Pugh thought of it too, and it’s satisfying to see the results of being on the same wavelength.

Despite selling 100,000 copies within a day of release, and a million copies within a year, The Stanley Parable wasn’t the career maker it could have been. Wreden went on to release The Beginner’s Guide in 2015, an intriguing but divisive narrative about an enigmatic game developer, and a game à clef for the shock Wreden experienced at being suddenly thrust into the limelight. He hasn’t released a game since. Pugh made the garrulous Dr. Langeskov, The Tiger, and The Terribly Cursed Emerald: A Whirlwind Heist, also a commentary on game design, and most recently collaborated with Justin Roiland on an obscure, ill-received VR game called Accounting.

Those thin resumes aren’t recapped to slight Wreden and Pugh, but instead to highlight how perfectly The Stanley Parable’s whirlwind success captured its moment. At a time when gaming was so achingly desperate to appear mature that great debates about the validity of staid “walking simulators” were launched with all the fervor of the crusades, The Stanley Parable parachuted in out of nowhere and used its quick, breezy wit to highlight how unique gaming is as a medium, and how we’re still coming to terms with its conceits. It’s not without flaws, but if you wind up getting referenced in House of Cards, you certainly did something right.

You can decide whether The Stanley Parable is art, but it certainly holds up better than many of its artsy contemporaries. The script still feels fresh, it (mostly) avoids dated references, it hasn’t suffered murder from a thousand memes à la Portal, and Brighting’s acting is timeless. Ebert, a genius to the last, had the good sense to expire rather than get sucked into another round of the “Are games art?” debate, but so many of the titles the yes campaign was argued with have been forgotten, aged poorly, or were never really all that great to begin with. Maybe Ebert was right, and no game will last for centuries. But The Stanley Parable is still a sheer delight to play today, and that’s a worthy legacy.