South Africa has 12 official languages. The two most dominant are isiZulu and isiXhosa. While the Zulu and Xhosa people share a rich common history, they have also found themselves engaged in ethnic conflict and division, notably during urban wars between 1990 and 1994. A new book, Divided by the Word, examines this history – and how colonisers and African interpreters created the two distinct languages, entrenched by apartheid education. Historian Jochen S. Arndt answers some questions about his book.

What is the key premise of the book?

The beautiful thing about history is that it can help us develop a more complex understanding of the things we consider natural in our daily lives.

People like to believe that their languages have always been there and always played an important role in defining their identity.

But history can show us that what appears to be timeless is, in fact, deeply historical and dependent on the actions of people with ambitions and agendas. My book argues that, as well-defined, standardised languages rather than speech forms (vernaculars), isiZulu and isiXhosa emerged as part of a long historical process that involved a wide range of actors, notably European and US missionaries and African interpreters and intellectuals.

How did you arrive at the project?

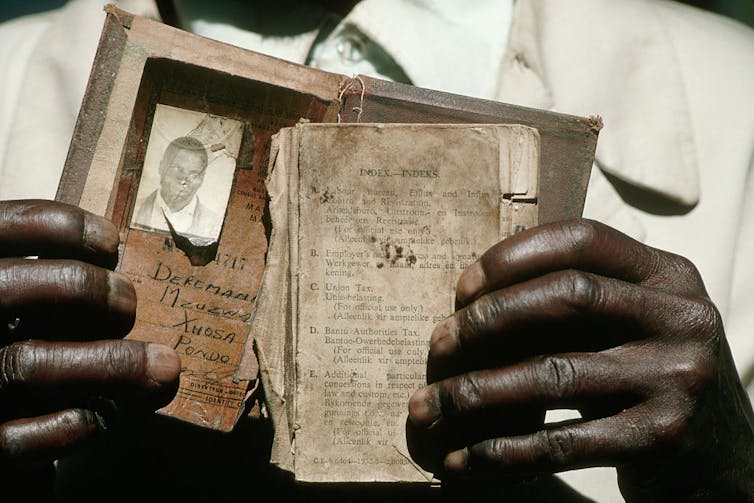

During the transition from apartheid to democracy in South Africa between 1990 and 1994, the urban areas reserved for black people around Johannesburg were engulfed in violence that killed thousands. Civil wars are always complex, but the testimonies of participants reveal that many of them understood the conflict as a war between Zulus and Xhosas. I was struck by how they defined Zuluness and Xhosaness. Many said they were Zulu because they spoke the Zulu language, and Xhosa because they spoke the Xhosa language. One haunting testimony was of a self-identifying Zulu:

The Xhosa who were trying to kill us were just looking for your tongue, which language you were.

My book argues that the historical process that produced isiZulu and isiXhosa as distinct languages began at least two centuries before apartheid. It was the product of colonial encounters and both foreign and African ideologies of language.

Was there a time when Zulu and Xhosa identities didn’t exist?

The subtitle of the book is: “Colonial encounters and the remaking of Zulu and Xhosa identities”. I’m not saying that Zulu and Xhosa identities didn’t exist before the languages were well defined, rather that the identities were transformed when these languages came into existence.

Read more: The 100-year-old story of South Africa's first history book in the isiZulu language

Before the 1800s, South Africa’s indigenous people had two key forms of collective belonging: the chiefdom and the clan. There were many chiefdoms and clans, including Zulu and Xhosa ones. The chiefdom was a political entity: a person belonged to a chiefdom because they had submitted or sworn an oath of fealty to a chief. The clan was a genealogical entity: a person belonged because they were born into the clan.

Membership in a chiefdom or a clan had nothing to do with language.

How did the two distinct languages come into existence?

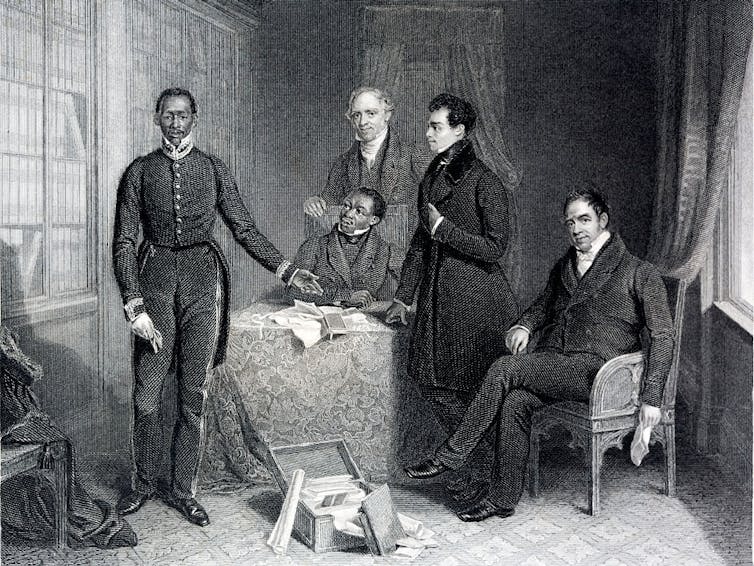

I argue that in the 1800s foreign missionaries and their African interpreters together created distinct isiZulu and isiXhosa out of numerous speech forms.

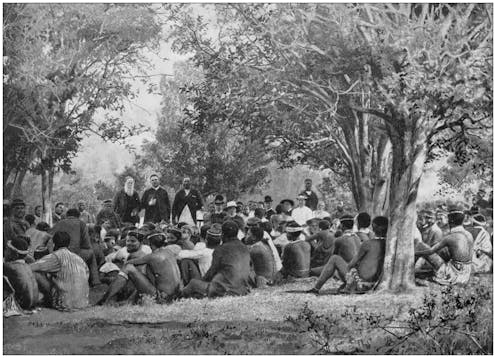

Protestant missionaries arrived in South Africa in the 1820s. Their primary goal was to convert Africans to Christianity. For them the Bible was the source of revelation. To give Africans direct access to it, it had to be translated.

The problem was there was no written language, so written languages and their geographic reach had to be defined. Consequently, missionaries asked themselves: are the speech forms of the Zulu and Xhosa and of the chiefdoms and clans in between them – such as Mfengu, Thembu, Bhaca, Mpondo, Mpondomise, Hlubi, Cele, Thuli, Qwabe – similar enough to represent a single language into which the Bible can be translated, or do they represent multiple languages?

I suggest that the answer to this question changed over time for a host of reasons, perhaps most importantly due to the influence of African interpreters. Missionaries depended on interpreters, who had their own ideas about language. The decision to think of isiZulu and isiXhosa as two separate languages can to some extent be traced back to these interpreters.

Education played the crucial role in people identifying with these languages. It involved Africans and non-Africans, as lawmakers, superintendents of education and teachers, promoting isiZulu and isiXhosa as part of “mother tongue” education in various school settings between the middle of the 1800s and the last decade of the 1900s.

How did apartheid entrench this?

Apartheid merely reinforced this trend. Crucial was the Eiselen Commission of 1949, which claimed that isiZulu and isiXhosa were the “bearer of the traditional heritage of the various ethnic groups”. This was like saying that these languages captured the essence of these groups in particularly powerful ways.

To reinforce these group identities, the commission expanded mother tongue education in schools. This for a Mpondo child, for instance, meant studying isiXhosa, and for a Hlubi child meant studying isiZulu. Children gradually assimilated Zulu or Xhosa as their language-based identities.

How is this relevant today?

Post-apartheid South Africa continues to promote the Zulu-Xhosa divide through its own official language policies in schools. In the Eastern Cape, for instance, African pupils will learn standard isiXhosa because it is assumed that their “home language” is a dialect of isiXhosa. In KwaZulu-Natal the same happens with isiZulu. Under this policy, it is very difficult to revive and strengthen identities such as Bhaca or Hlubi.

The only way out of this predicament for the Hlubi and Bhaca is to make language a battleground of their identity politics. I think this best explains why the Hlubi have created an IsiHlubi Language Board and why the Bhaca insist that their speech is not a dialect of isiXhosa.

My point is that we cannot make sense of their need to make these arguments without coming to terms with the long history of the Zulu-Xhosa language divide.

Jochen S. Arndt received funding from the Social Sciences Research Council, American Historical Association, and Association for the Study of the Middle East and Africa.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.