Rise and grind”. “Your workout is my warm-up”. The word “Girlboss”, written over and over again. In the Disney Plus adaptation of Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s hit novel Fleishman Is in Trouble, slogan T-shirts are the uniform of a certain tribe of New Yorker.

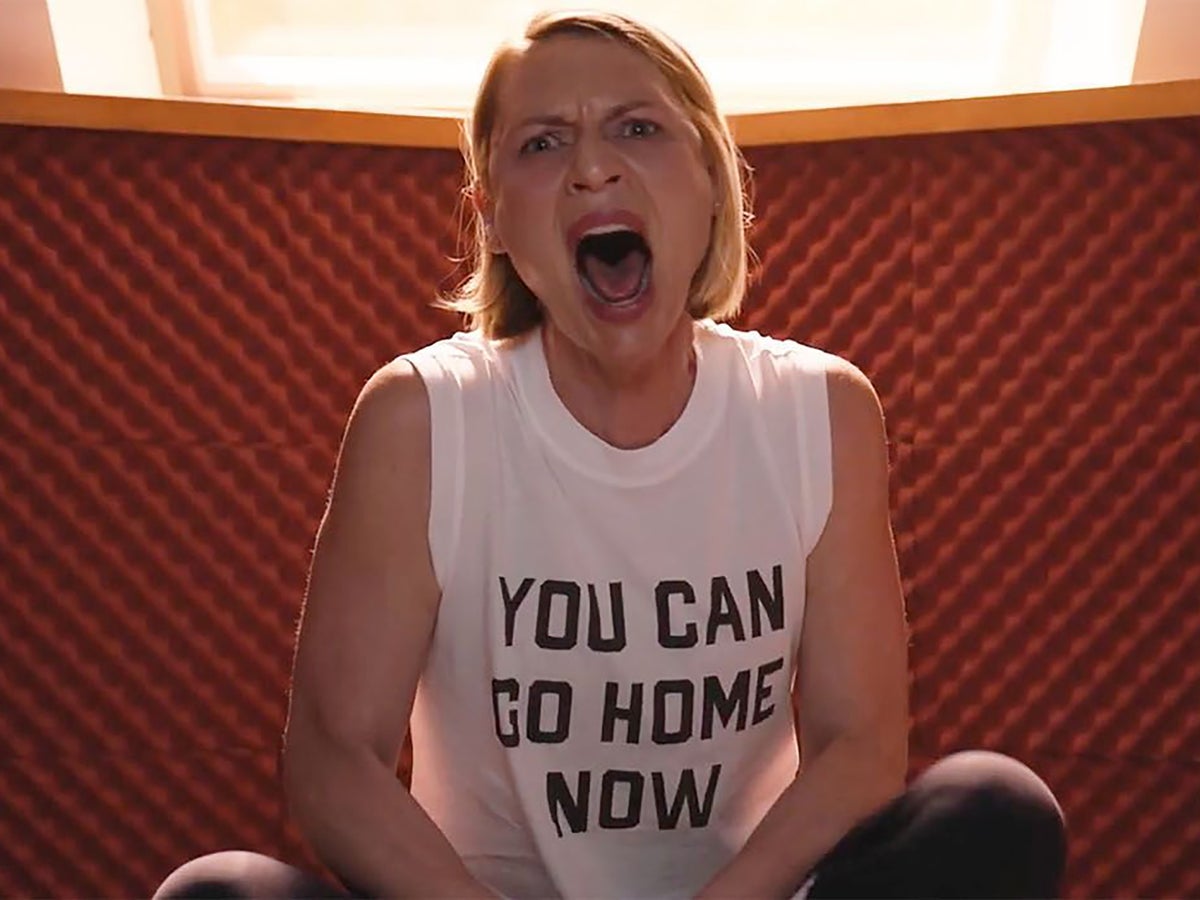

Whether newly divorced dad Toby Fleishman (Jesse Eisenberg) is waving his kids off to summer camp, trawling the aisles of an organic supermarket, or swiping through a dating app, he is surrounded by women whose clothes shout vaguely empowering, yet slightly foreboding, messages. The most enigmatic motto is reserved for his ex-wife Rachel (Claire Danes), whose exercise top simply reads: “You can go home now.”

In Brodesser-Akner’s story, these designs are the yoga class attire for a coterie of wealthy Upper East Siders; their daughters wear T-shirts promising that “the future is female”. Fleishman is set in 2016, during the summer of the Trump campaign, but the sharp writing, combined with costume designer Leah Katznelson’s clever styling, manages to skewer the state of the mainstream slogan T-shirt in 2023, too.

Enter a high-street clothing shop, or scroll through Asos, and you will find tees espousing #feminist mottos (“I can buy my own damn flowers”) in a faintly pass-agg tone (“Unfriend mute unfollow block”). It’s a far cry from the era of designers Katharine Hamnett and Vivienne Westwood, who mobilised the slogan T-shirt to make it synonymous with boundary-pushing political activism. So how did this once-edgy garment become so... basic?

Humans have used the symbols on their clothes to proclaim their beliefs for centuries, explains Dr Ben Wild, senior lecturer in fashion cultures at Manchester Fashion Institute, part of Manchester Metropolitan University. Back in the 11th century, “one of the leaders of the First Crusade, Godfrey of Bouillon, apparently ripped up one of his most precious robes into the sign of the cross, and then handed it out to people who said they were [joining the] Crusade,” Wild says. “And then that emblem [was] essentially sewn onto their garments. So this idea of branding the body to demonstrate allegiance to a cause is age-old.” When we wear a slogan, he adds, we are trying to “embody that message” or “value”.

The first protest T-shirts emerged in America in the late Sixties, as part of the movement against the Vietnam war – “an easy and affordable way for grassroots activists to signpost the issues they cared about”, as J’Nae Phillips, editor at trend forecasters Canvas8, puts it. On this side of the Atlantic, the designer Mr Freedom was selling Pop Art-inspired printed tees in his King’s Road boutique in Chelsea, London. The premises would later become Westwood and Malcolm McLaren’s SEX boutique – home to their infamous “Destroy” T-shirt; the pair described the contentious design, which also featured a swastika and a crucifix, as a statement against fascism.

An average T-shirt uses 2,700 litres in the growing and production process, which equates to an average person’s water consumption for 2.5 years

In the Eighties, Hamnett made headlines with her legendary styles, designed so that their slogans could be read “from 20 or 30 feet away”, as she later told The Guardian. Her “Choose Life” tops, worn by Wham!, were “inspired by the Buddhist lifestyle” and were “meant to represent the idea of living a good and meaningful life, and taking steps to change the world for the better”, says Lynne Hugill, principal lecturer in international fashion at Teesside University and a former designer for high-street fashion retailers.

When Hamnett was invited to Downing Street to meet with Margaret Thatcher, she let her clothes do the talking. Her T-shirt read “58 per cent don’t want Pershing”, a reference to polls showing that the public opposed plans to station American nuclear weapons in the UK. When Thatcher cottoned on, Hamnett recalled, she “made a noise like a chicken”.

The same decade, Wild says, saw the “mass commercialisation of fashion”, when the market was “flooded with branded goods”. This shift, he explains, made us increasingly comfortable with the idea of “using our bodies in a fashion space to proclaim our allegiance, be it to a brand ... [or] our social-political values”.

This stepped up a gear in the logo-obsessed Nineties; then, as we entered a new millennium, slogans became increasingly tongue-in-cheek. Think of Britney Spears’s “Dump Him” tee (seen as a message to her ex-boyfriend Justin Timberlake’s rumoured new girlfriend, Alyssa Milano), or Madonna being papped in a “Cult Member” top at the peak of frenzied reporting about her interest in Kabbalah. Celebrity activism was not yet fashionable – instead, these designs allowed stars to hit back at tabloid gossip. Henry Holland’s rhyming T-shirts (like “I’ll Show You Who’s Boss, Kate Moss” and “Cause Me Pain, Hedi Slimane”) brought this winking humour to the catwalk. More recently, slogans have started “to address positivity, community spirit, and health and wellness, like the Sporty & Rich ‘wellness’ T-shirts”, adds Hugill.

The slogan tee has managed to pique the interest of both high-end and lower-price labels – “Luxury as well as high-street brands [have] jumped on the bandwagon,” Phillips says. It lets designers demonstrate their charitable credentials while still flogging a zeitgeisty product – a nifty “merging between commerce and conscience”, according to Wild.

In 2015, Dior’s Maria Grazia Chiuri sent models down the runway wearing “We Should All Be Feminists” T-shirts, a nod to writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s rallying call. “That [was] obviously tapping into an urgent social cause, but there [was] also a sense that it had been commodified, because it had been marketed and sold at quite a high premium,” Wild notes. It was a move that – ironically – risked “cheapening and reducing that message”. Did shoppers really need to spend around £500 to prove their feminist credentials? (Dior later agreed to donate a proportion of profits to its then brand-ambassador Rihanna’s charity, the Clara Lionel Foundation).

When there’s a dissonance between the message on the shirt and the conditions in which the garment was made, the slogan tee risks becoming a contradiction in terms. Our growing awareness of the ramifications of fast fashion “has meant that people have started asking a lot more questions when it comes to where T-shirts are being sourced from”, says Jo Salter, founder and CEO of social enterprise Where Does It Come From?, which creates ethical and sustainable clothing and textiles. “In the past, because supply chains were much more opaque,” she adds, “no one ever found out” about bad practices. “But now with globalisation and [better] communications, we can find out much more about what’s going on.” It’s a shift that is “forcing brands to become increasingly transparent with their resourcing and manufacturing”, Hugill agrees.

Although cotton is a natural fibre, she explains, it often has a high carbon footprint – so unless the manufacturers have looked carefully at their supply chain, a tee with a green message might defeat the object. “An average T-shirt uses 2,700 litres in the growing and production process, which equates to an average person’s water consumption for 2.5 years,” Hugill says.

When the Fawcett Society teamed up with Whistles to create a “This Is What a Feminist Looks Like” tee in 2014, the design was modelled by the likes of Emma Watson, Alexa Chung and, erm, Nick Clegg. The £45 design sparked controversy, though, when a report alleged that the Mauritian garment workers had been paid just 62p an hour (the Fawcett Society later said they had seen “evidence” that “categorically refute[d]” the allegations).

Five years later, Comic Relief released #IWannaBeASpiceGirl charity T-shirts in collaboration with the band – only for The Guardian to claim that they had been made in a factory where female workers were subject to poor conditions and low pay. Not very Girl Power. Online retailer Represent eventually took “full responsibility” for the debacle, after apparently having changed supplier without telling the band or the charity.

Scandals like this didn’t finish off the feminist tee. Just as trends are diluted on the journey from catwalk to high street, so mottos often get similarly watered down when they are brought to the mass market, resulting in the pseudo-empowering word jumble we see in Fleishman. Still, these styles do serve a purpose of sorts. Slogans speak to “the need we often feel, particularly now, to connect, to feel part of something larger than ourselves”, Wild says. They can help us to “reach beyond the noise ... stake a claim, [show] we want to be part of something”. Even if that “something” is loving gin, or being good at cardio – it’s still a conversation-starter.

Organisations like Salter’s can help these garments to find a new lease of life. In 2021, she was asked to help electric vehicle company Trywyre to make carbon-neutral campaign T-shirts after Cop26. “What we decided to do was to source T-shirts that were already on their way to landfill,” Salter explains. “So we found these T-shirts that had #freebrittany on them.” Intended to cash in on the battle against Spears’s conservatorship, these condemned tees had namechecked “the region in northern France” instead. Salter’s project eventually saved 540 garments from landfill; it provides a salutary lesson about where pop-culture-inspired designs might end up once the moment has faded (and the importance of proofreading).

The contemporary slogan tee isn’t all about living, laughing and loving. Hamnett’s work remains as political as ever; her recent designs are emblazoned with phrases like “Cancel Brexit” and “Be an Anti-Racist”. And Ashish’s 2016 “Immigrant” T-shirt felt like an appropriate emblem for London’s diverse fashion scene. What’s most important to remember, though, is that wearing your beliefs on your chest is never enough to make change. As Hamnett herself put it: “A successful T-shirt has to make you think, but then, crucially, you have to act.”

‘Fleishman Is in Trouble’ is streaming on Disney Plus now