Danger lurks in the surf beaches of Australia in the form of rip currents or rips. These narrow, fast-flowing, seaward channels of water are responsible for an average 26 drownings a year and 80-90% of the thousands of surf rescues. Yet, unlike other well understood and feared natural hazards such as bushfires and floods, the ever-present menace of rip currents is often overlooked.

Until now, the firsthand effects of rips on the people caught in them had also been overlooked. Not enough was known about the human element of rip currents – who is getting caught, what their experience is actually like, what they know about rips, and what information about rips people are likely to understand and remember.

Research concentrated more on physical characteristics of the hazard, such as flow dynamics and types of rips. This is important, and such findings have been used to develop the best strategies to escape a rip. But understanding the human element is essential too.

With this in mind, we interviewed 56 rip current survivors for our newly published research. Their recollections painted a vivid picture of their experience. They offered invaluable insights into how people respond to being caught in a rip.

Read more: Don't get sucked in by the rip this summer

Many survivors were naive about the risks

Many interviewees had been naive and unprepared for encountering a rip. They knew little about rip currents and didn’t understand the dangers. They confessed to overestimating their swimming abilities and underestimating the conditions.

Some described approaching the ocean as though it was a swimming pool.

We just basically ran into the water, as you do when you arrive at the beach, you throw down the towel, and we just raced into the water.

What is being caught in a rip like?

Once caught in the rip’s grip, panic was a very common response, leading to a mental “fog” that hampered decision-making.

Even if you know what to do it’s hard to put that into action when you’re actually in the rip […] because your first emotion is panic.

This visceral fear led to dangerous mistakes. Many survivors had tried to swim directly against the powerful current - a potentially fatal strategy.

I actually did think I was gonna die, I thought, ‘Oh my God that’s it, I’m gonna drown, that’s ridiculous […] how can I drown? That’s ridiculous,’ but I really did think that was it. […] I couldn’t think clearly enough to work out what to do.

The aftermath of these experiences painted a distinct picture. All the interviewees emphasised nothing could match the actual experience of a rip current for understanding its force and handling its threats. They felt current safety information, though plentiful, wasn’t as effective as it could be.

Perhaps if people can get a sense of when they’re in a rip what are some of the sensations […] it’s about giving people some pointers of what it feels like to be in a rip […] I think for a lot of people it doesn’t really mean anything, particularly visitors, if they haven’t had a lot of experience.

These interviews underscore the complex human aspects of the problem. Our strategies can’t just focus on stopping people from entering rips. This is practically impossible, as people will always want to swim at unpatrolled locations.

Survivors shared a conviction that personal experience was the greatest teacher.

Once you understand rips, I think the fear of them disappears because you can use a rip to your advantage.

Read more: Australia's spike in summer drownings: what the media misses

What are the lessons for surviving rips?

While throwing everyone into a rip current for “experience” is hardly feasible, innovations such as virtual reality could provide a safe, controlled approximation of the experience. The importance of personal experience also underscores the need for Surf Life Saving programs such as Nippers – immersive education for children and young people in a controlled environment. As one survivor told us:

Most of us learn from our experience, and I think you have to experience things before you appreciate the reality of them. I certainly all these years have never really truly appreciated the enormity of a rip until I got caught into one.

Our study identified the potential for psychological prompts to jolt swimmers out of their “rip fog”. These prompts could guide them to make the best escape decisions and resist panic that could cloud their judgement. Signs could be placed on the beach, providing simple, clear messages such as “REMAIN CALM” if caught in a rip.

One interviewee recalled having to “slap” a person during a rescue to get him to focus on escaping the rip.

Just as I got to him he had just given up […] I could see it in his face as I was swimming to him, and the only thing above the water was this much of his arm and that’s what I grabbed, and I pulled him up out of the water, and I slapped him across the face because […] I saw the look in his eye as he went under and it was sort of, well I don’t know, resignation? And so I smacked him and yelled at him that, you know, he had to help me, that I couldn’t do this by myself.

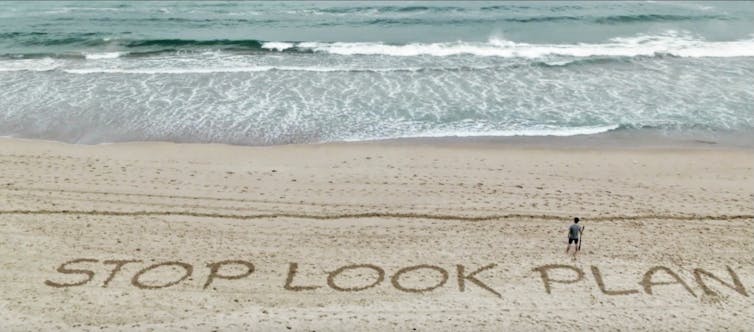

Our research underscores the need for innovative, behavioural solutions, such as Surf Life Saving’s Think Line campaign. This “line in the sand” aims to get people to stop to think about the risks before entering the water, look for rips and other dangers, and plan how to stay safe.

By integrating these insights into rip current safety strategies, we can promote a safer, more informed relationship between beachgoers and the sea. And that could reverse the tragic trend of increased drownings at our beaches.

For more about rip current safety and to find your nearest patrolled beach visit Beachsafe.

Samuel Cornell was employed as a Research Assistant by the UNSW Beach Safety Research Group to conduct this work. The UNSW BSRG received funding from Surf Life Saving Australia.

Amy Peden receives funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council. She maintains an honorary affiliation with Royal Life Saving - Australia as a Senior Research Fellow. The UNSW Beach Safety Research Group receives funding from Surf Life Saving Australia.

Rob Brander receives funding from Surf Life Saving Australia and the Australian Research Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.