As unprecedented as it is to say, we’re getting two completely different live-action Batmen on-screen at the same time in the next few years, which is a far cry from the uncertainty of the early 2000s. After the spectacular failure of 1997’s Batman and Robin, Warner Bros. had somehow taken one of the most lucrative properties in their catalog and turned it radioactive. As the years rolled by, the studio entertained every possibility from a live-action Batman Beyond film to a Darren Aronofsky/Frank Miller collaboration, but in truth, it was almost as if the bat was biding its time.

Enter an audacious firecracker by the name of Christopher Nolan. With little more than a critical darling of a psychological neo-noir to his name, what Nolan had in spades was vision, and after a pitch meeting that lasted less than an hour, Warner Bros. was seeing it too. As it turns out, cinematic history was being made. Batman Begins was the reboot to write the book on reboots, stripping the hero down to his core and thrusting him into the cynicism of a post-9/11 world before ultimately rebirthing him in a baptism-by-fire.

Despite four theatrically-led blockbusters at that point, the Dark Knight’s genesis had never properly been told on-screen, a prospect that fascinated Nolan. While the broad strokes of the character’s trauma were well known, the particulars of how an angry, narrow-minded playboy became a city’s tortured savior were less familiar. Nolan and co-writer David S. Goyer pored over Batman’s sacred texts, stealing bits from stories like Year One and The Man Who Falls to weave a story that centered Bruce Wayne just as much as it did the cape-and-cowl.

The result is a sweeping, bombastic adventure split into two parts: Bruce Wayne’s journey of self-discovery across the world and eventual training with the draconian Ra’s al Ghul, as well as his homecoming and crusade to topple Gotham’s criminal underworld as Batman. It’s a pulpy fusion of Lawrence of Arabia’s globe-trotting scale along with the simmering aesthetic of urban decay found in Taxi Driver, and the juxtaposition mines pathos out of its central hero.

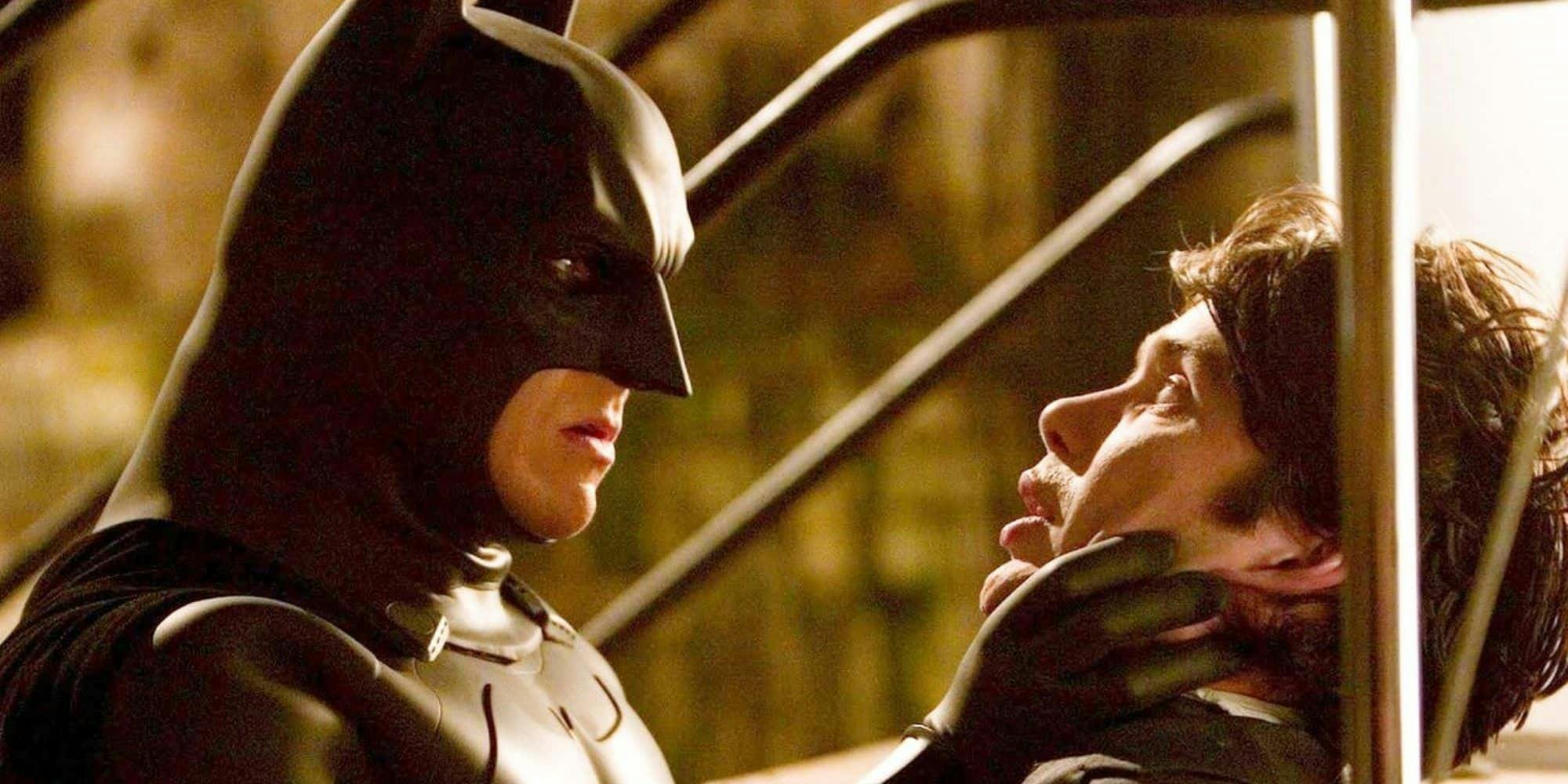

Christian Bale’s Bruce Wayne, unlike the brooding eccentricity of Michael Keaton or the suave charm of the Kilmer/Clooney era, was the first time the character felt like he was fighting himself. Bale’s incredible versatility as an actor carries the film through the many volatile points in Bruce’s life, shaping and reshaping the anger that consumes him into so many different faces. After returning to Gotham, Bale puts on Patrick Bateman’s uncanny mask of ego to shield his true intentions from the world at large, and as Batman, he leans into the vigilante’s theatricality and rigid physicality in a way that feels genuinely threatening.

While Bale nails Bruce Wayne’s tortured psyche, his relationship with Michael Caine’s Alfred is what pulls him back from the brink and makes up the lifeblood of the Dark Knight Trilogy. In previous depictions of the character, Alfred was little more than an actual butler that Bruce was particularly fond of, but Nolan was the first director to showcase the complexities of their relationship and Alfred’s place as a father figure of sorts. The two veteran actors craft a heart-warming friendship, and Alfred’s unflinching dedication to Bruce is showcased by his refusal to leave him in any situation, be it as a young boy in need of a hug or a grown man who needs help “lifting a bloody log.”

It’s not just Bruce’s relationship with Alfred that Nolan was content with reimagining, however. From the ground up, all of Gotham City was conceptualized wholly anew. Gone was the Gothic architecture of Burton’s Art Deco hellscape, as well as the gaudy neon aesthetic of the Schumacher films. Nolan was intent on presenting audiences with a “recognizable, contemporary reality against which an extraordinary heroic figure arises,” which is why his Gotham feels indistinguishable from a real metropolitan city like Chicago or New York. Nolan’s Gotham is one choked by wealth inequality, a city in which ordinary citizens cower in desperate fear at the corrupt structures keeping things from getting better.

Coupled with this new vision of Gotham is a pair of villains that reflect Nolan’s desire for something more tangible. Cillian Murphy’s soft-spoken, shrewd, and uncanny depiction of Jonathan Crane is a tragically underrated villain performance, and despite the egregious white-washing of Ra’s al Ghul via Liam Neeson, the romanticized mentor-and-student camaraderie he shares with Bruce during his training is still what makes his betrayal so riveting. Ghul’s grand plot to flood the streets of Gotham with Crane’s fear toxin is still probably one of the most logical villain schemes in a major superhero release, and the horror of the outbreak in the Narrows during the film’s third act visually echoes the chaotic pandemonium of Ground Zero, an event that Nolan would explore the aftermath of throughout the trilogy.

One particularly understated example is how Nolan, inspired by the mobilization of American police post-2001, militarizes his vision of Batman. The audacious costuming of the Schumacher era is replaced by a lean and efficient Batsuit that emphasized functionality over form, plus the flowing gothic cloak that had been the centerpiece of many of the iconic images Nolan had come across in his research. One of the best scenes in the film is watching Bruce and Alfred stock, test, and cultivate Batman’s toolkit: it not only emphasizes the self-made nature of the character, but it also contributes to the Bond-esque espionage feel the movie sometimes has.

There’s also the introduction of the immediately iconic Tumbler, a Batmobile so cinematic and similar to real-world military vehicles that you could mount a strong argument for it being pop culture’s default image when asked what Batman’s ride might look like. Production designer Nathan Crowley designed the tank from the ground up in miniatures, before moving to a full-scale styrofoam replica, a steel-frame test version, and finally, four street-ready versions that each filled a specific purpose during production. The final result is one of the most menacing cars in cinematic history, and it’s easy to recall just how exhilarating it was seeing the Tumbler launch across rooftops back in 2005.

Nolan’s films are celebrated for redefining the concept of what superhero films could be, but there are also critics quick to deride them for abandoning the outlandish, supernatural elements of the character to gain mainstream appeal. Indeed, Batman Begins birthed the reboot craze of the early 2000s, giving us a few gems such as Casino Royale, but also a host of imitators that believed the easiest path to financial success was to take a formerly juvenile blockbuster IP and drag it through the muck. “Dark and gritty” became studio shorthand and the bane of audiences, and by the time the Power Rangers got the same treatment, the trend had been well and truly driven into the ground.

But what studios never quite understood is that Nolan hadn’t changed Batman all that drastically. In stripping him of a fantastical world filled with fantastical powers, he simply emphasized the sweeping scale of the character’s adventures. The result was a reminder that the true strength of the Dark Knight lies in his incredibly human willpower.

Batman Begins is streaming on HBO Max through February 28.