In 2021, Zack Snyder did the impossible. With the help of a passionate (and arguably toxic) online fanbase and an army of Twitter bots, the director pressured Warner Bros. into finally releasing the so-called Snyder Cut. Sort of.

Zack Snyder's Justice League amounted to a $70 million reshoot of the 2017 movie that featured additional CGI and at least one entirely new scene. It was a monumental moment and a bizarre chapter in the history of superhero cinema. But it also wasn’t the first time a director had to play the long game to bring their original vision to the world. There is perhaps no greater testament to the raw power of editing and the magic of a cohesive artistic vision than the journey of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, from the original theatrical release of 1982 to the triumphant Final Cut that arrived 25 years later.

We’re talking, of course, about the original, infamous director’s cut: Blade Runner. The Final Cut is streaming now on Max, but it leaves soon. Here’s why you should watch it, and what to know before you do.

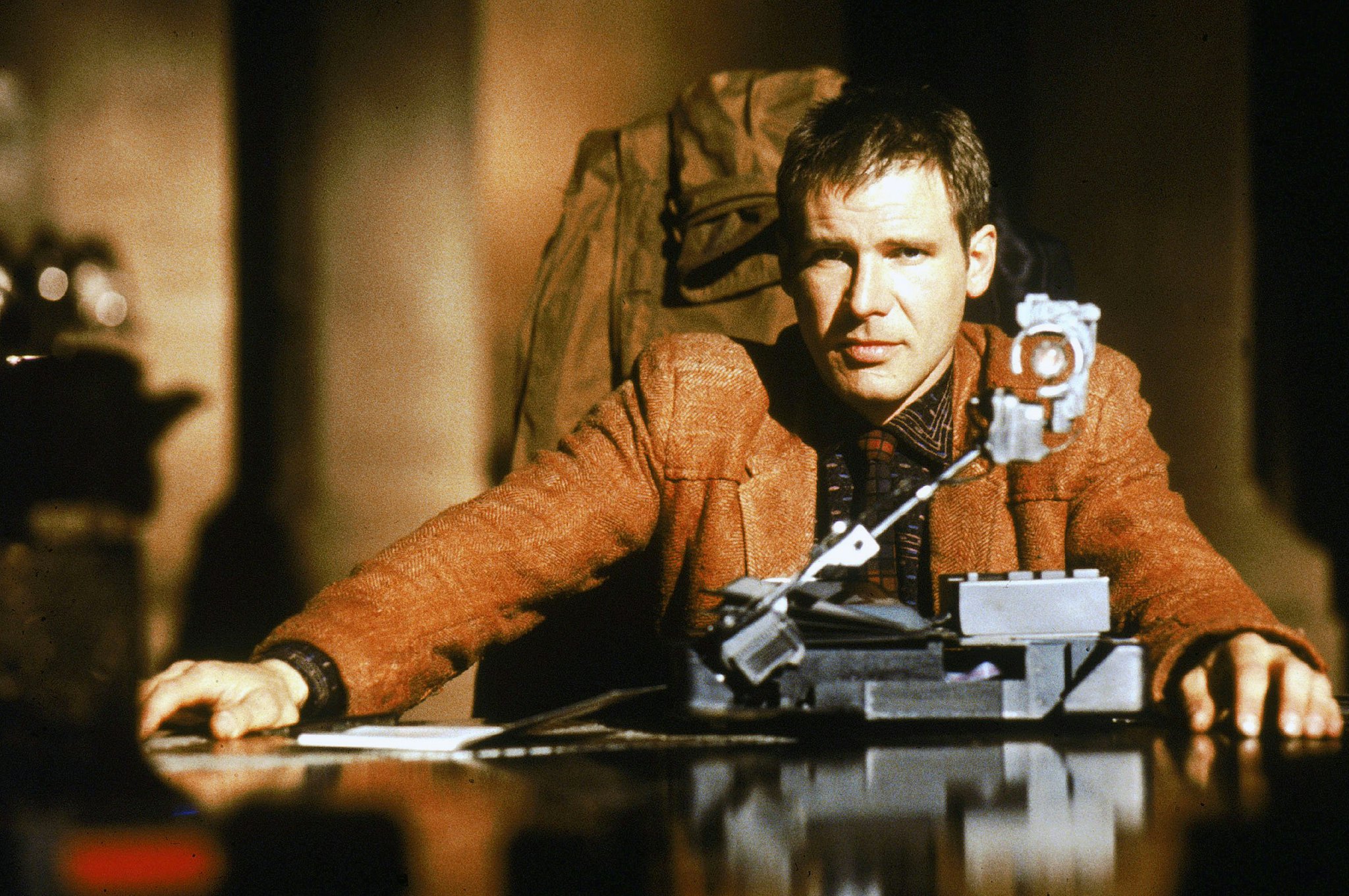

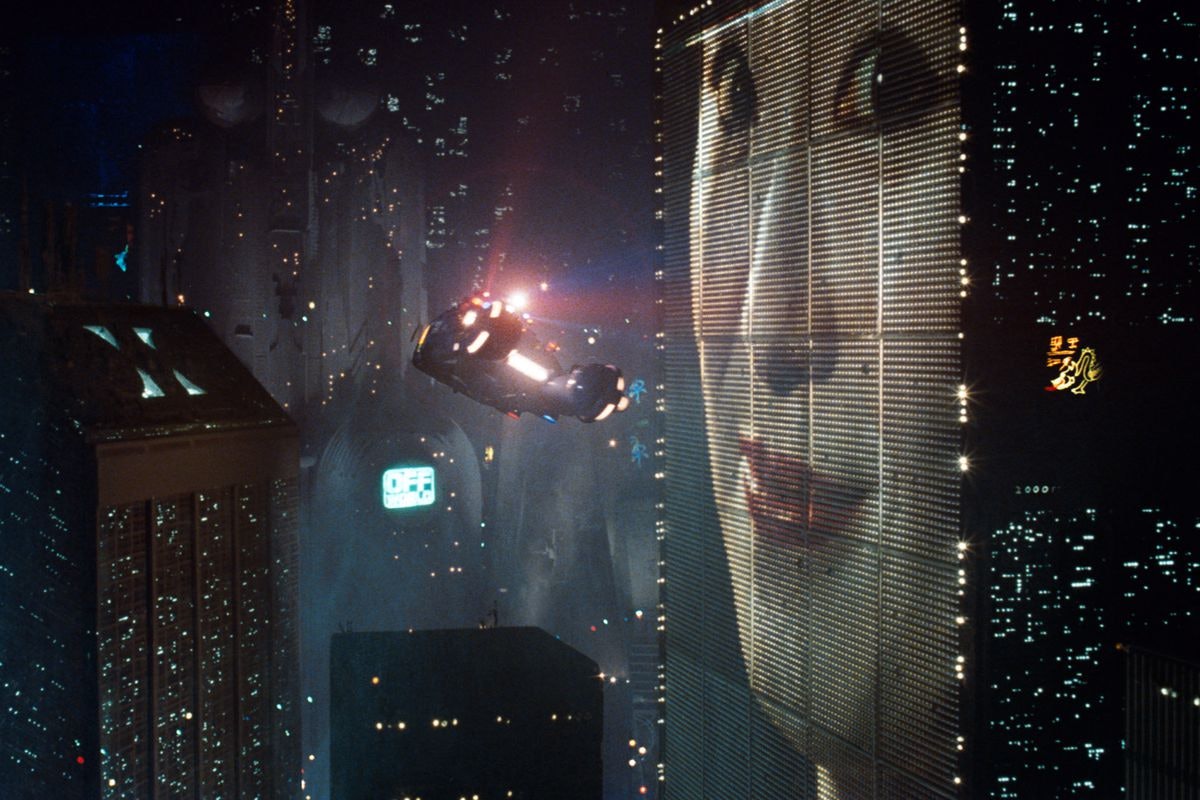

It’s borderline impossible to imagine what pop culture would be like without the impact of Rick Deckard’s (Harrison Ford) melancholic odyssey through a neon-lit dystopia, hunting down rogue androids named Replicants and trying not to consider the implications raised by their cruelly limited lifespan. The DNA of the film can be seen throughout not just cyberpunk, but the science-fiction genre as a whole. Akira, The Fifth Element, Strange Days, and so many more owe their entire existence to what Ridley Scott accomplished.

But looking back in awe after 40 years leaves out a key piece of the story: the grueling crucible it took for Blade Runner to gain the reputation it now enjoys. When the film was theatrically released in 1982, it was wildly divisive. The dense world-building and sparse plotting found in Scott’s original cut received negative responses at test screenings in March of 82, causing the film’s producers to step in and severely alter the resulting theatrical release.

Among the debilitating changes was the notoriously awful voice-over narration performed by Harrison Ford, a misguided attempt to clarify the film’s story as well as evoke the gumshoe detective noirs of the ‘40s. The other (and debatably more egregious) change from Scott’s original plan was the film’s theatrical ending: Deckard and Rachel, the Replicant he falls in love with, somehow escape the urban dystopia and climate cataclysm of Los Angeles and run off to... a scenic woodland paradise? To make matters worse, Deckard’s insufferable narration also explains that the four-year lifespan all Replicants suffer from simply doesn’t apply to Rachel, stripping both characters and the movie itself of any lingering tension.

The damage was done: Blade Runner’s theatrical release made $41.6 million on a $30 million budget, and for years it was criticized as a slow-paced, pretentious example of style-over-substance. However, even in its broken theatrical state, the film gained a loyal following who appreciated the quiet decay of Scott’s vision of the future, as well as its heady questions about the very nature of humanity. So when a preserved copy of the film’s original version began screening and selling out in Los Angeles and sporadically across the United States in 1990 and 1991, both diehard fans and new audiences began to understand just how radically the movie had been altered — and Warner Bros. began to see dollar signs all over again.

After continuing to show Scott’s original vision in limited theaters for several months, Warner finally commenced work on an official “Director’s Cut,” reaching out to Ridley Scott for detailed notes and creative input. Although the actual curation of the project was spearheaded by film restorationist Michael Arick, the “Director’s Cut” was the first time that Scott’s genuine creative vision for the movie was championed. Gone was Harrison Ford’s sleepwalked narration, as well as the jarring and unearned happy ending — now and forever does the movie end with the stark uncertainty of a closing elevator door, leaving Deckard and Rachel to a future not meant for our eyes to see.

Of course, the “Director’s Cut” still didn’t relinquish final cut privileges over to Ridley Scott — that didn’t happen until 2007, with the release of the aptly titled Blade Runner: The Final Cut. Not all that dissimilar to the Director’s Cut, it features the full version of the unicorn dream, as well as the addition of sequences that were originally only in the international release of the film. However, the importance lies in The Final Cut existing as the culmination of over two decades of artistic reclamation, a project that has retroactively turned a confounding box office dud into one of cinema’s most profound works of science-fiction philosophy. All the pieces were already there, and had been since 1982: breathtakingly human performances, camerawork both staggering in its scale and dreamlike in its intimacy, and the raw creative ingenuity to create such a spectacular vision of the future. All that was missing was the passage of time and the perspective granted by it.