Forget the head-in-a-box twist of Seven, the mistaken identity tragedy of Night of the Living Dead or the sacrificial denouement of The Wicker Man (the original not the unintentionally hilarious Nicolas Cage in a bear suit remake). No other horror has left audiences teetering on the edge of existential despair more effectively than this Stephen King adaptation. Just ask the author himself, who argued the 2007 release boasted “the most shocking ending ever.”

King, obviously in a hyperbolic mood, also proposed “there should be a law passed stating that anybody who reveals the last five minutes of this film should be hung from their neck until dead.” But we’re hoping 16 years on this particularly harsh statute of limitations has now passed.

He was talking, of course, about The Mist. And with only a few days before it leaves Netflix on June 21, there’s never been a better time to indulge in its unremittingly bleak final scene. Here’s why. Warning: Spoilers ahead!

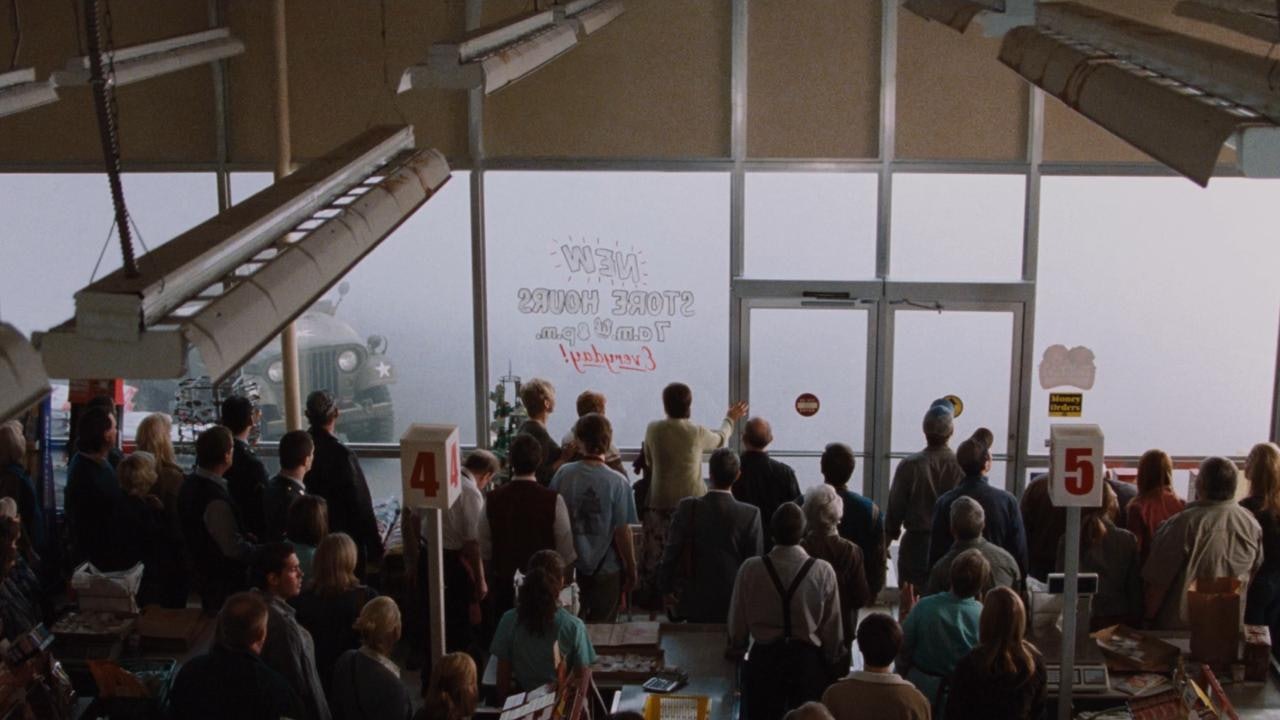

Based on the same-named novella that appeared in King’s 1980 anthology Dark Forces, The Mist finds a bunch of small-town locals trapped in a supermarket that’s suddenly become ensconced in a thick fog. As the few who dare to venture outside find out to their cost, this freak weather is also hiding some tentacled Lovecraftian creatures whose shopping list consists solely of human flesh.

Director Frank Darabont was no stranger to lifting King’s words from the page to the screen. He made his debut with 1983’s The Woman in the Room, a short film adapted from the horror maestro’s Night Shift collection. Then, in 1994 he famously elevated The Shawshank Redemption to high art before returning to the prison period drama five years later in The Green Mile.

Darabont wrapped these two feature films up slightly differently to their source material. In Shawshank, corrupt penitentiary warden Norton shoots himself to avoid prosecution, whereas in the book he simply resigns. Red (Morgan Freeman) is also shown breaking parole rather than just preparing to, resulting in the emotive beachside reunion with Andy. In Green Mile, meanwhile, the news death row officer Paul’s wife Jan has perished in a road accident and that he’d subsequently been visited by the executed John’s ghost is completely omitted.

Nevertheless, these alterations didn’t really affect the overall narrative. But for The Mist, however, Darabont wanted an ending that would stun both newcomers and fans who’d read all 176 pages of the novella. Luckily, King was more than happy to give his blessing. (“We need movies that dare piss people off,” he said.) The sucker punch is all the more unexpected, too, for the fact the film had stayed relatively faithful for the previous 110 minutes.

Sure, the relationship between painter-turned-action hero David (Thomas Jane) and revolver-carrying teacher Laurie (Amanda Dunfrey) had been switched from adulterous to strictly platonic. Darabont wanted to create a surrogate family between the pair and David’s eight-year-old son Billy (Nathan Gamble). There’s also a more detailed explanation for the monster-shrouding mist — a Stranger Things-esque government experiment to open up new dimensions that had badly malfunctioned. But The Mist still always appeared to be heading in the same ambiguous direction as the book.

Indeed, after overpowering religious zealot Mrs. Carmody (Marcia Gay Harden, more terrifying than any of the man-eating beasts) and her followers’ unhinged attempt to sacrifice Billy and Amanda, the ‘good’ survivors decide to take their chances outside. Ollie (Toby Jones) is immediately killed in the parking lot. Then, following a detour to David’s home, where it’s confirmed wife Stephanie (Kelly Collins Lintz) has died, the remaining survivors run out of gas.

King leaves things open-ended. (“My father had nothing but contempt for such stories, saying they were ‘cheap shots,’” goes the narrator’s meta-commentary.) David hears a reference to the town of Hartford in a radio transmission, giving him a slither of hope the world hasn’t entirely been obliterated. Darabont, however, makes the remaining characters’ fates crystal clear.

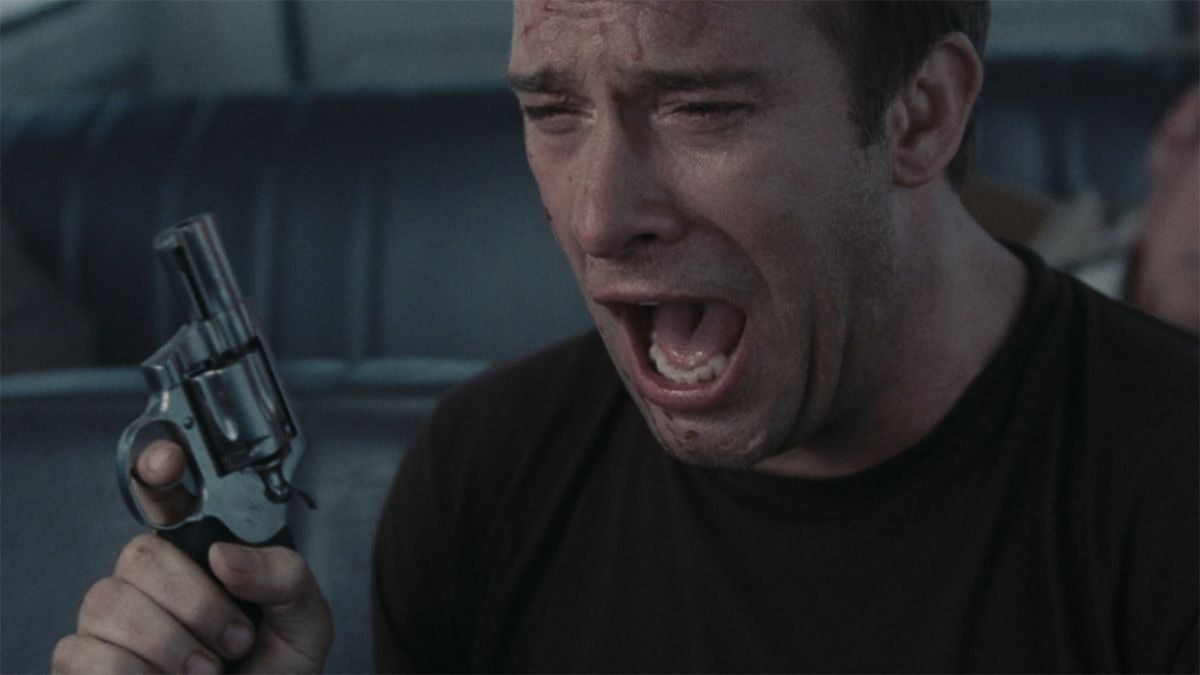

Instead of waiting for what would appear to be an inevitable limb-by-limb mauling, the group decides to exert the only bit of control they have. David will shoot Billy, Amanda, and the elderly Dan (Jeffrey DeMunn) and Irene (Frances Sternhagen) with the four bullets left before offering himself up to the invaders.

Darabont wisely avoids showing any graphic details, pulling back from the intimacy inside the Toyota Land Cruiser for a faraway shot of all the gunfire. We do see a clearly-distressed Billy, though, just seconds before the trigger is first pulled, suggesting he was painfully aware of what was to come. This alone would be a desperately sad resolution: the cinéma vérité style adopted, inspired by the filmmaker’s love of The Shield; and the sparse soundtrack makes the traumatic events seem even more eerily realistic. Yet remarkably, there’s worse to come.

As a grief-stricken David exits the vehicle to wait for his own gruesome demise, the mist suddenly begins to clear, revealing a U.S. Army vanguard on a rescue mission. Had he waited just a few minutes,his only child and his three friends could have looked forward to a future without the threat of pterodactyl-like mutants. Cue the agonizing sound of David’s tormented cries as the camera pans out to the new safer world.

It’s an outcome no one saw coming. Well, apart from Carmody whose claims the mist would only subside after the sacrificing of Billy and Amanda proved to be strangely prophetic. And it’s one which could be interpreted as a testament to the power of faith. The God-fearing Carmody is spared by the praying mantis-esque creature that climbs up her chest. Instead, her death comes at the hands of the gun-toting Ollie, while those who clung to her every word are presumably still alive. Yet those who gave up all hope were punished in the most harrowing way imaginable. Whether intentional or not, the revised ending only heightens King’s story.

The Mist’s uninspired TV adaptation a decade later proved how tricky it can be to reinterpret the novelist’s work. Darabont, who sadly hasn’t helmed a picture since, not only made it look easy, he set a new benchmark for cinematic pessimism.