Every year in lutruwita/Tasmania, tens of thousands of people journey to and meander through the island state and take in festivals such as Dark Mofo, Cygnet Folk Festival or Nayri Niara Good Spirit Festival.

Part of the pull of this place and its cultural offerings are the landscapes in which such events are placed: picturesque mountain ranges and deep valleys; vast open paddocks and pristine bushlands; glistening coastlines; quirky city spaces.

As human geographers, we understand that festival landscapes are more than a party backdrop. They are not waiting, ready to greet us like some sort of environmental festival host. They have Deep Time and layers of meaning.

But when they become spaces for creative adventures, these landscapes also have profound effects on how people experience festivals, affecting our sense of place, of ourselves and others.

Festivals come with specific boundaries – dates, gates or fences – and mark a period and place in which we experience some shifting of social norms.

In our research, we wanted to explore how festivals affect people’s sense of place, self and other.

As Grace, an avid festival-goer, told us “social expectations that come with adulthood get removed at a festival.”

I don’t know what happens when you walk through the gate of a festival [..] you leave all that behind and you step into what feels like […] a more authentic version of yourself. Or at least a freer one.

Creating spaces

A lot happens to make a festival landscape.

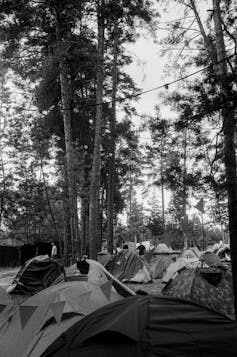

Teams of staff and volunteers establish campsites, install rows of toilets that often are also composting works of art, build stages, lay kilometres of pipes and power chords and design paths, sculptures and dance floors.

These collective labours create a special atmosphere; serve basic needs for sleep, food, hydration, warmth and sanitation; invite journeying to and from; and foster relationships to places and sites via immersive experiences and hands-on engagements with the landscape itself, for itself.

Travis, a stage-builder and DJ, told us:

if you use what’s already there, then [the stage] blends in with that whole environment and ties in to how people see it and how people feel in it.

Marion, a festival artist, spoke of her desire to show care and respect by creating work that “doesn’t impose and can […] naturally be reabsorbed” into the landscape.

She described how all of the rocks for a labyrinth at one event came from the festival site. Once, the sheep who lived there walked through on their usual path – destroying her installation.

Read more: The environmental cost of abandoning your tent at a music festival

Transformative experiences

When people attend festivals, they often attach themselves to the landscape and detach from their daily lives: they are looking for transformative experiences.

In lutruwita/Tasmania, festivals such as Fractangular near Buckland and PANAMA in the Lone Star Valley take place in more remote parts of the state.

Grace, from Hobart, told us that being in those landscapes taps into

something that humans have done forever […] gather around sound and nature and just experience that and feel freedom.

Even when festivals are based in urban landscapes, the transformation of these spaces can evoke a sense of freedom.

For Ana, a festival organiser, creating thematic costumes is part of her own transformation.

At festivals she feels freedom to “wear ‘more out there’ things”.

If I was on the street just on a Wednesday I’d have to [explain my outfit] […] Whereas at a [street] festival[it] flies under the radar.

Body memories

Festival landscapes have features conducive for meeting in place (think open spaces, play spaces, food and drink venues) and for separating out (think fences and signs).

Commingling at festivals can literally lead people to bump into each other, reaffirm old bonds and create new connections through shared experiences.

One artist, Marion, told us:

When you go and you camp, you get burnt together, you get wet together, you dance together. [It creates] an embrace for me.

Festivals often linger in people’s memories, entwined with bodily experiences. People we spoke with talked about hearing birdsong and music, seeing the sun rise and fall over the hills and feeling grass under their dancing feet.

While one-off events can be meaningful, revisiting festivals may have an especially powerful effect.

Annual festival pilgrimages become cycles of anticipation, immersion and memory-making. This continuing relationship with a landscape also allows festival goers to observe how the environment is changing.

As festival organiser Lisa said:

since 2013 […] every summer our site just got drier and drier. 2020 was the driest year of all. There was no creek. There was just a stagnant puddle.

Writing new stories

The COVID-19 pandemic led organisers and attendees to rethink engagements with live events. Many were cancelled; some were trialled online.

But after seasons of cancellations, downscaling and online events, some festivals in lutruwita/Tasmania are back, attracting thousands of domestic and interstate visitors.

For those festivals that have disappeared, their traces remain in our countless individual and collective stories of the magic of festival landscapes.

Read more: Without visiting headliners, can local artists save our festivals?

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.