Improving the chord voicings within your song or production will add a musical element that will help elevate your work to the next level. But to help explain what a voicing is, you’ll forgive us if we kick-off with a food related analogy! All musicians like food, right?

Think of a bowl of spaghetti, with all of that lovely tomato sauce on top; the spaghetti is our chosen chord symbol, and the sauce is/are the notes contained within that chord. We need to blend/mix the two elements together, so that the notes (sauce) are spread evenly throughout the chord (spaghetti). That’s what we call a voicing!

It’s essentially how we arrange and place the notes across the range of instruments that we’re using.

Of course, we’ll have to finish our foodie analogy by asking about the parmesan topping; yep, that’s the tune or melody that sits on top of your newly blended and voiced chords…obviously!

If you’re still reading, it means that you’ve managed to allay your hunger pangs for a moment, and you’d like to know how to voice a chord.

Your approach to this will likely be enlightened by the instrument that you play. Many of the principles of voicing are informed by the chord progression that you’ve written, and while guitars can voice chords beautifully, the archetypal rock guitar often works on a tradition of bar chords, which for our purposes is not really what we’re after here.

So, we are going to describe voicing with relationship to a keyboard or piano. However, it’s important to stress that a good voicing can be transported to many other settings, and 95% of keyboard voicings translate to string sections, synth pads, brass sections, horn sections, sax sections…you get the picture!

Like so many aspects of the music drawn from the contemporary musical culture of today, it’s enormously informed and influenced by the contemporary pop culture of a bygone age; namely a composer called Johann Sebastian Bach (JS to his friends) who lived around 300 years ago.

He was akin to the biggest influencer and music technologist of his day, while also being an enormous musical innovator.

He laid down many of the musical ground rules and regulations that so many of us use, knowingly or otherwise. Rules are obviously there to be broken, but his concepts and approaches will make your music sound better.

Time for the drop

Let’s start looking at some of those Bach-ian principles in an attempt to improve our work. Sticking with our piano, we’re going to start with a specific chord in mind.

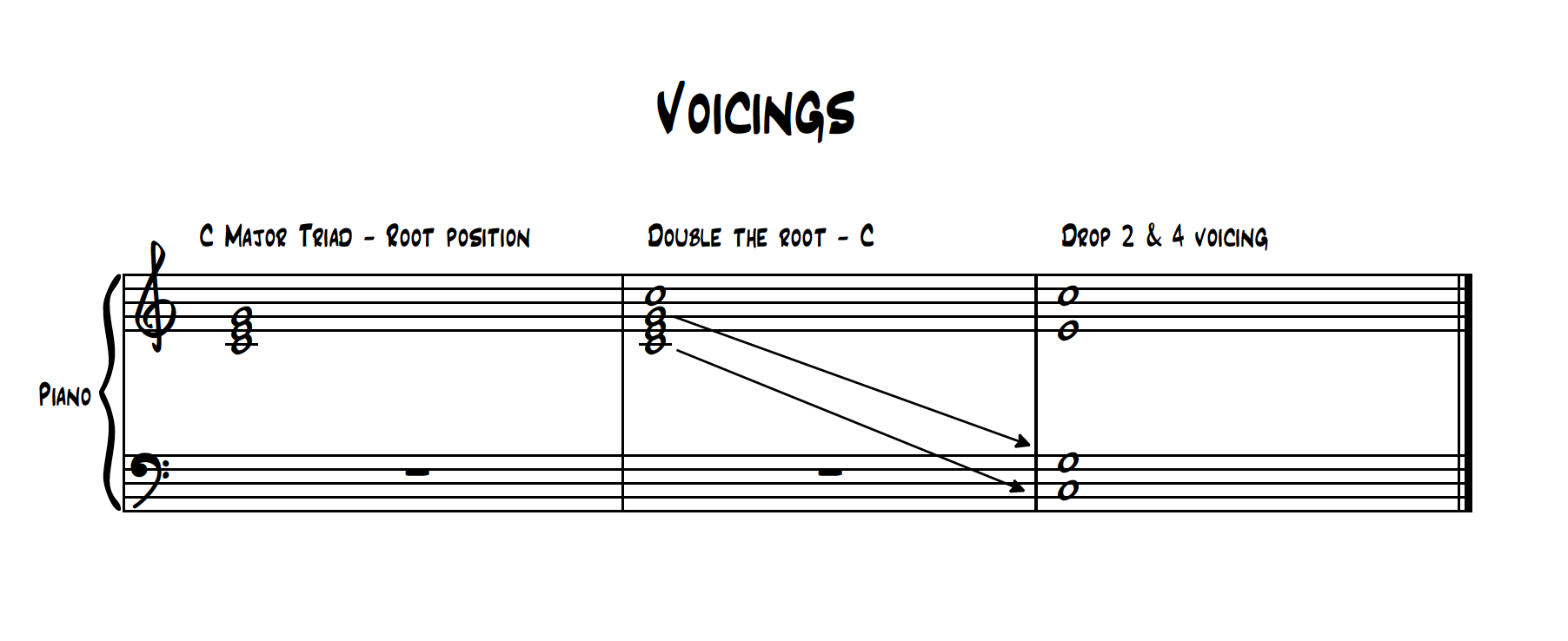

Keyboard players like the key of C major, so we’ll go with our old favourite and imagine that we have a triad of C major, formed from the notes C, E and G

We are going to re-order the notes in the chord to create a voicing, but before we do that, we are going to double the root of the chord, the note ‘C’. We now have the notes C, C, E and G.

If we lay these notes out from bottom to top, with middle C at the bottom, we have a closed chord. There’s nothing wrong with that, but if we shift a couple of the notes in the chord, we can create a greater expanse across the range of our piano keyboard.

Start by dropping the lowest note of the chord (middle C) by one octave. This immediately makes the chord sound like it has more stature.

Now drop the note ‘G’ to one octave lower too. We now have a beautifully spaced chord, which spans two octaves. Can you imagine this played on a string section? Very sweet and tasty indeed!

By shifting these notes around, we have created a voicing which is known in musical circles as a 'drop 2 and 4 voicing', and moreover, it’s incredibly common because it sounds so good!

The numbers relate to the position of the notes in the original chord. While we often work from the bottom up, in voicing-land we work from the top down. Hence, we moved or ‘dropped by an octave’ the 2nd and 4th notes down in our chord, hence drop 2 and 4 voicing.

Progressing the progression

Applying this voicing principle to a single chord is easy enough, but what do you do if you have a sequence of chords in a song?

The art of voicing could also be regarded as the art of orchestration or arranging, regardless of whether you have an orchestra to hand or not. What we’re looking to do is apply similar designs to other chords, while also applying a technique which is known as voice or part leading.

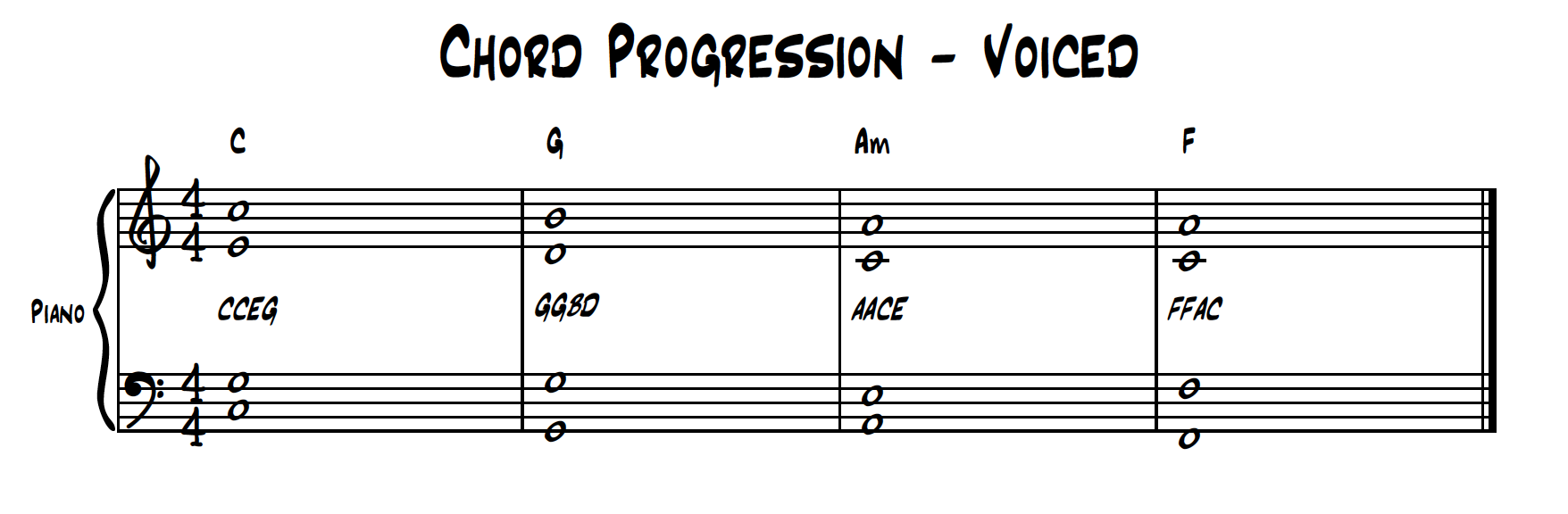

We’ve been working on the principle of a triad, where we double the root of the chord, giving us four notes. We are going to continue with this principle, but now within the context of a chord progression. We’ll work with four chords; C major, G major, A minor and F major - very familiar and common choices.

Now imagine that wherever possible, we want to make each note of each chord move as seamlessly as possible, from one chord to the next.

Step-wise movement is always favourite, but sometimes small leaps might be required, and if your lowest note is keeping to the roots of the chords, it will have to jump around a little bit. It simply can’t be avoided.

In our example above, note that the top line moves downward in steps, as do the middle two parts, with an exception where one note in the 3rd voice has to make a small leap.

The lowest part, which could also quite nicely double as the bass part in a song, has to do a bit of inevitable leaping, but it will still sound very convincing.

There are a couple of other useful tips to try and adopt, that will strengthen your voicing cause. In this context, it’s often a good idea to avoid parallel movements, particularly the movement of two notes in parallel that form the interval of a 5th or an octave.

This is one of those JS Bach rules, the concept being that parallel movement sounds weak. Having said that, rock guitars often work entirely on the principle of parallel 5ths, so much so, it’s become part of the instrument’s psyche. We’re obviously not suggesting changing that, or the rock gods will rightly have something to say.

On an associated note, try to get your upper and lower parts to move in opposite directions, as they move from chord to chord. This level of voice leading, where one part goes up and the opposite goes down (and vice versa) will sound strong in the context of a progression, and that can only be a positive.

It would be easy to ponder why rules that have quite literally been in place for the last 300 years might have any relevance today.

The truth is, they are adopted for a reason, as legends such as George Martin will attest, as he often kept The Beatles on track, helping them to make their songs as beautifully formed as they are through the use of these directives.

You can only break the rules if you know what the rules are, and these few simple points will have an incredibly positive effect upon your musical and production output.