Out of 225 people awarded the Nobel Prize in physics, only five have been women. This is a very small number, and certainly smaller than 50% – the percent of women in the human population.

Despite several studies exposing the barriers for women in science and the many efforts to increase their representation, physics continues to be a male-dominated field. Only 1 in 5 physicists are women, a number that has not moved since 2010.

Three of the five Nobel Prizes in physics awarded to women have been in the past decade. As a woman physicist, seeing three women join the cadre of Nobel laureates in Physics in just a handful of years is beyond exciting.

Nobel Prize-winning work

The three woman physicists receiving Nobel Prize honors in the 21st century are Donna Strickland, who won in 2018, Andrea Ghez, who won in 2020, and Anne L’Huillier, who won in 2023. All three made important contributions to science.

Strickland, a physicist from the University of Waterloo, won the award for her work on lasers, implementing a method called chirped pulse amplification.

Ghez, an astrophysicist from UCLA, got the Nobel for her work observing stars, especially those near the center of the Milky Way.

L’Huillier, a physicist from the University of Lund, received the 2023 Nobel, also for her work with lasers.

What are some common threads in their lives?

Being a minority in a research field isn’t easy. Sticking with it long enough to have a storied career, as the three winners have, is a huge accomplishment. Since winning the prize, the three winners have recounted their research journeys and offered advice to the next generation of physicists in a variety of interviews. I’ve noticed a few common threads.

A career in academia is a long haul. All three women emphasize the timescale involved in going from first steps in their research to being recognized by the Nobel committee. L’Huillier refers to it as a long journey.

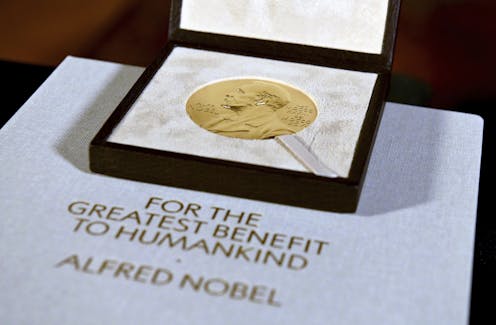

While winning a Nobel may come with some glamour and notoriety, if you are after a quick reward, this career may not be the right line of work. It now takes an average of 28 years between publishing a discovery and receiving a Nobel in physics.

You cannot predict which basic science topic is going to lead to a Nobel – nor, for that matter, which will end up having any kind of impact. The best an early-career physicist can do is to explore different topics, try new things, lean into discomfort and find something they’re passionate about.

All three women talk about how many times they ran into difficulties. Before she got the chirped pulse amplification method to work, Strickland had started to wonder whether she would ever get a Ph.D., having hit so many dead ends. The first time Ghez proposed the project that would lead to her celebrated work, she was turned down.

All three of them thought of quitting at some point. So don’t be discouraged if you are turned down or if others say you cannot do it.

“Keep going,” says L’Huillier. “You need to be obstinate.”

Ghez recommends seeing experiments that don’t work not as failures but as opportunities.

Movies and TV shows paint a picture of the scientist as a social misfit, an individual working alone in the laboratory. But that’s not how it works. All these women work in teams.

“Science is a team sport. You need to know what you don’t know and seek help for what is missing,” says Strickland.

Seeking help often leads to collaborations with other research groups. As Ghez puts it, “Science is a very social enterprise.”

And above all else, the three medalists referred to luck as an essential ingredient for success. The world is full of physicists just as dedicated and just as smart who don’t get the Nobel.

Themes specific to women

Strickland, Ghez and L’Huillier are always asked about their experiences being a woman in science and their views on diversity and equity in physics. All of them emphasize the importance of diversity.

The three laureates have recognized how critical female role models have been in their lives. To believe a physics career is even possible, you need to see people in the field who look like you.

They also mention the importance of a support network, especially for women. Having a group of people you trust to cheer you on can help when you feel discouraged.

The three women also talk about their experiences balancing work and life. It’s not always easy.

Strickland left the standard academic path after a postdoctoral fellowship to become a technician so she could be close to her husband and start her family. L’Huillier walked away from her job and moved from France to Sweden, where she was unemployed for a while. Ghez waited years to have kids. There is no single trajectory. But time away from research can give you fresh perspectives and inspiration to take the next steps.

They also talk about how diversity enriches the research itself. A team that is open to different points of view is more creative. It is also more fun to work in.

These women have pointed out that the culture for women in science has improved over their careers and they are optimistic about the future. If you calculate the percent of Nobel Prizes in physics awarded to women in the past decade alone, then about 1 in 10 Nobel recipients have been women. To me, this indicates that, indeed, things may be getting better.

And perhaps the Nobel committee is addressing, at least in part, possible gender inequities in their processes. For example, the lack of nominations of women and the influence that stereotypes could play in their evaluations. So it is with great expectation that I await this year’s announcement.

Filomena Nunes does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.