In the fourth season finale of "Yellowstone," Kevin Costner's John Dutton III announces his candidacy for governor of Montana by proposing a simple platform. "I am the opposite of progress," he tells the state's prospective voters. "I'm the wall that it bashes against, and I will not be the one that breaks."

The sixth-generation rancher makes good on that promise in his victory speech, his win being a foregone conclusion from the moment he threw his wide-brimmed hat in the political ring. After all, since Dutton is the patriarch of the largest contiguous cattle ranch in the United States, he may as well be the entire region's big daddy.

He promises his constituents to protect Montana's clean air, water, and pristine forests by canceling airport and real estate development funding and penalizing non-residents with additional taxation.

"The message is this: We are not your playground. We are not your haven from the pollution and traffic and mismanagement of your home states. This is our home. Perhaps if you choose to make Montana your home, you will start treating it like a home and not a vacation rental."

Upon hearing this, his son Jamie (Wes Bentley) complains that John just set back the state 30 years. Jamie's sister Beth (Kelly Reilly), a daddy's girl to her marrow, crows that he's thinking too small. The plan, she says, is to set it back by a century.

"Yellowstone" is often described as the red states' answer to "Succession," although its co-creator, showrunner and occasional guest star Taylor Sheridan scoffs at that. If the show holds a particular appeal to conservatives, and it does, that aligns with Montana's political bent, along with the other wide-open spaces in the Western United States that don't touch the Pacific Ocean.

Then again, so what? Just as Logan Roy's fanbase includes plenty of people he wouldn't allow to shine his shoes, John Dutton's bravura and the rest of his family's messiness is truly a big tent affair.

"Yellowstone" is the "Dallas" of our day, in the same way that real estate ownership and development can be thought of as the 2022 equivalent of oil wealth. The nighttime soap was a hit for CBS back in the late 1970s, as "Yellowstone" is for Paramount Network today; more than 13.4 million viewers watched the fifth season premiere on Paramount Network, Pop, CMT and TV Land.

But it's also doing something that only a few years ago may have seemed unlikely: it's reviving the Western's popularity on the small screen.

The Western never completely disappears from TV, especially if you broaden your interpretation of what shows qualify to wear that shield.

All of these shows juxtapose the violence and ruthlessness that define the genre with mesmerizing cinematography reflecting the West's untamed allure.

Contemplating the genre's modern standard-bearers requires deep tribute to "Deadwood," of course, along with reminders of underappreciated achievements such as the 2017 series "Godless" or the 2019 east-meets-Western cult hit "Warrior."

One must also credit "Breaking Bad" and "Sons of Anarchy," a show on which Sheridan worked, for clearing a path for "Yellowstone" to travel, although the Dutton's saga's tone straddles the ground between that of "Longmire" and "Justified" – which is also getting a revival. In 2023 Timothy Olyphant reprises the role of Deputy U.S. Marshal Raylan Givens in "Justified: City Primeval."

Quite a list, proving that any claims that that Western was dead at any time over the past two decades aren't accurate. But it did lay fallow for a time. "Westworld" certainly didn't put it back in the saddle.

In fairness "Yellowstone's" role in boosting the frontier tale's fashionableness is also a matter of fine timing, politically and circumstantially speaking. "Yellowstone" debuted in 2018, smack in the middle of a presidential administration that forced us to question and bicker over the meaning of American identity. Such debates are the heart of the Western's tableau, stories that ultimately come down to survivalist clashes of will and character, determining who gets to shape a culture's story.

The drama only really achieved hit status during the pandemic, when hemmed-in city dwellers gaped at its shots of pristine vistas and open skies and Googled cost of living comparisons between Montana and wherever they were living. Statistics listed in U.S. News and World Report indicate the state's population grew by 1.1% in 2020 followed by 1.6% growth in 2021. This has driven up real estate prices too, with the median home price now nearly double what it was in 2020 at $500,000.

Real estate brokers refer to this as the "Yellowstone Effect."

If television is experiencing its version of that, it's much seeded by Sheridan's other work.

The first "Yellowstone" spinoff, a prequel called "1883," broke viewership records when it premiered last year; another chapter of the Dutton family saga, "1923," hits Paramount+ on Dec. 18. What they lack in the poetic grit that defined shows such as iconic series such as "Deadwood," they make up in impressive household names, including Harrison Ford and Helen Mirren.

"1883" features Faith Hill and Tim McGraw starring as John Dutton's great-great grandparents alongside Sam Elliott as the hired gun protecting them and other white settlers traveling the Oregon Trail from the East. Even Tom Hanks makes a cameo.

This year also begat "Billy the Kid" from "Vikings" creator Michael Hirst, which failed to hold its storytelling reins as securely as these other titles.

Not to be left behind, Prime Video gave us Josh Brolin in "Outer Range" and, more recently, debuted a six-episode revenge saga "The English," from filmmaker Hugo Blick.

It's a meandering story elevated somewhat by Emily Blunt's engaging performance as an English noblewoman, Lady Cornelia Locke, who teams up with Chaske Spencer's stoic Eli Whipp, a Pawnee army officer trying to leave his military life behind to farm in Nebraska. However flawed its narrative execution may be, however, the cinematography is beyond sublime, capturing the natural radiance of the grasslands and endless blue above.

That, as much as anything else, lends to the renewed attractiveness of the Western. All of these shows juxtapose the violence and ruthlessness that define the genre with mesmerizing cinematography reflecting the untamed allure of the mountains and prairies. Following so many years of grim, sweaty anti-heroes grimacing through dim spaces or slugging it out in grime, the Sheridan-influenced West is an unspoiled treasure worth fighting over.

That's another point of evolution: each of these series questions the rights claimed by self-appointed custodians like John Dutton, who crusades against careless profiteers, given that the land came under their ownership because their white predecessors took it from the Indigenous peoples who lived there for centuries before Europeans arrived in North America.

Westerns roam the landscape of history, and that topography is ever-changing and constantly contested.

When Sheridan pushes back against claims that the show is right-wing steak served rare, he points out the recurring themes of Dutton's pushback against environmental degradation, along with ongoing plotlines about Indigenous peoples' displacement after white settlers seized their land, backed by the government.

On "Yellowstone," the Confederated Tribes of Broken Rock, whose reservation adjoins the Yellowstone Dutton Ranch, are now contending with a neighbor who holds the most powerful position in the state promising to protect the state's natural resources by driving away tourist revenue.

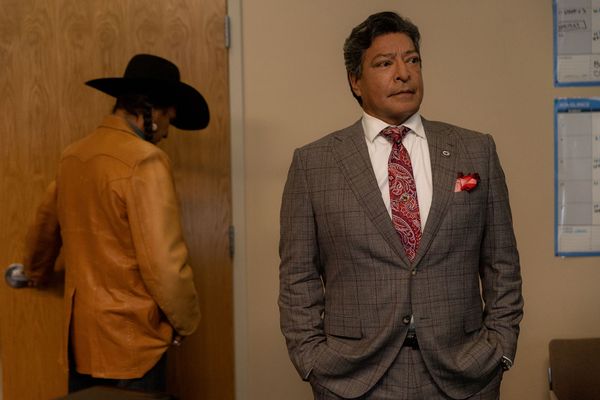

"It's a good thing for the land," tribal chairman Thomas Rainwater (Gil Birmingham) says of Dutton's aggressive executive orders, "but I don't see how it's good for us." There's a long history there, shown in "1883" when his ancestors violate Native American territorial boundaries and, elsewhere in "The English," where Eli's insistence on claiming what the government says he's owed for his military service is constantly met with reminders that he isn't white and, therefore, his life is worth less that of a white man.

Nostalgia is the Western's fuel, which explains why it keeps resurfacing at inflection points in our culture. "Gunsmoke," which held the record for the prime-time scripted series that produced the most episodes in TV history until "The Simpsons" surpassed its 635 episodes, emerged after World War II.

The fact that it held on through the social turbulence caused by the war in Vietnam and the Civil Rights Era is a telling indicator of America's devotion to its self-established mythology. Westerns roam the landscape of history, and that topography is ever-changing and constantly contested. Recent years remind us of this, especially as politicians fervently attempt to legislate versions of history that don't suit their agendas out of classrooms.

In the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s movie theaters, cowboys became the moral equivalent of gray hats, until we eventually we met a brighter-spirited cowboy in the form of, yes, Kevin Costner in "Silverado" and, later, "Dances with Wolves."

The version he presents in "Yellowstone" via John Dutton is closer to the Clint Eastwood archetype with a touch of J.R. Ewing's determination, with a little more gravel in his voice and whiskey in his attitude. Dutton's goal isn't expansion, it's holding on to his questionablyattained acreage and with it, his dominance over all he surveys. He is the image looking back at those who stare into the mirror, searching for either a threat or some sign of what the nation looks like at this moment.

Depending on who you are, maybe you're cheering the sight of him, or watching to celebrate his tumble. Either way, he has us turning our gaze Westward again, for however long this genre gold rush lasts.

"Yellowstone" airs at 8 p.m. Sundays on Paramount Network. Past seasons stream on Peacock. All episodes of "1883" are streaming on Paramount+. All episodes of "The English" are streaming on Prime Video.