It must have been the nerves.

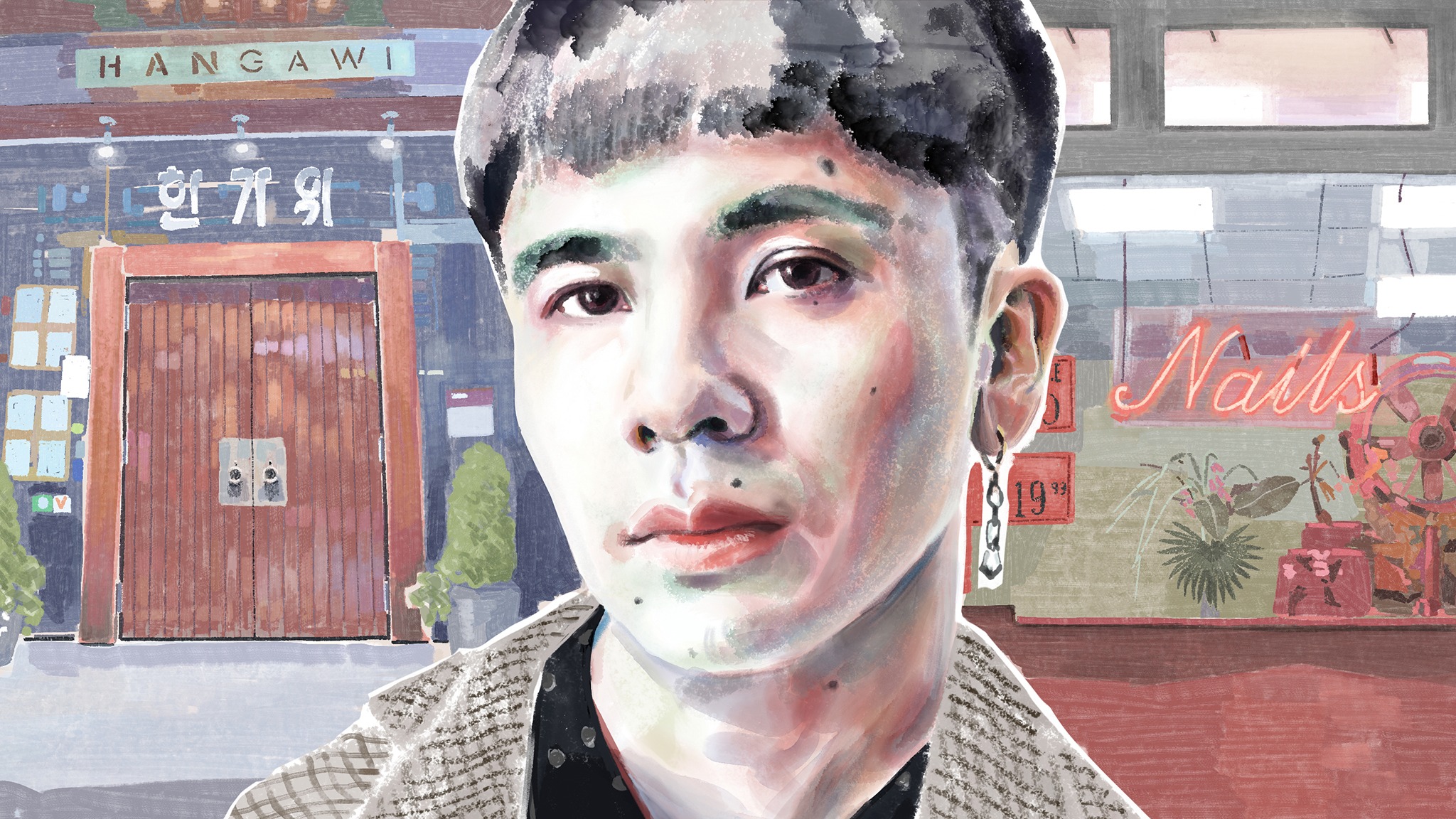

When the hostess at HanGawi asked me to remove my shoes, I couldn’t. I was at the Korean restaurant to meet Ocean Vuong, author, literary darling, MacArthur genius, rare celebrity poet and, I noticed, a bit of a fashion plate. But with one frantic tug, my boot laces turned into a spectacular Gordian knot.

Diners remove their shoes when they enter HanGawi, part of the restaurant’s reverential ambience. It would be later in the meal — once I had recovered my composure — that I would notice the overhangs of pagoda rooftops, the dusky wood and ruby floor cushions that help transport diners far away from this unremarkable block in Manhattan.

We sit on the floor and slide our feet into a hollow carved beneath the table, and I ask Vuong if he chose HanGawi so that we could be shoeless.

“No”, he laughs, but he was told it would be quiet. “I call restaurants sometimes and say, ‘This is my voice, will you be able to hear me?’” I nudge my phone, recording our lunch, further towards his elbow.

Vuong was propelled on to the literary scene in 2016 with his award-winning poetry collection Night Sky with Exit Wounds. His novel On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous followed three years later, part kaleidoscopic love letter to his mother, part mythologisation of Vuong’s own life story: the queer son of a Vietnamese refugee nail salon worker growing up poor in New England and reckoning with the inheritance of war.

There is only today, when my mother is not here, and yesterday, when she was . . . When I look at my life now, I just see it in two days

His work charts a constellation of the millennial experience, and the quiet storm of the opioid crisis before it had a name. It also asserts that there is beauty in survival for first-generation immigrants. The intimacy and vulnerability of his inventive writing has secured the 33-year-old a cult following.

With his birdlike physicality, Vuong has the air of a fashion model, dressed in a blousy, collared shirt and high-waisted trousers. “I think of [Joan] Didion,” he offers, referring to his own diminutiveness. The American journalist famously once said that she was so unobtrusive and unthreatening that “people forget my presence runs counter to their best interests”.

“Invisibility, which is a constant hindrance to Asian-Americans, is an advantage in that I can see everyone,” Vuong says, pausing. “It’s up to me to turn this limitation into a superpower.”

He is preparing for the launch of his latest book, a poetry collection titled Time Is a Mother. The book is also Vuong’s first work since losing his own mother, his “north star”, who passed away from cancer in late 2019. “Everything I did, I did for her,” he says.

The decision to write was not to process his grief — though anyone who has lost a parent will certainly find themselves within his new collection.

“You don’t lose your mother and say, ‘Now I’m going to write a book’,” he says. The return to poetry was because “I was working towards pleasure, and poetry is where I have the most pleasure.”

The food at HanGawi is vegetarian, and so is Vuong. Well, vegetarian-ish. He eats fish sauce, or else, he says, “my Vietnamese card would be demolished”. Both overwhelmed by the menu and failing to focus on it, we opt for the prix fixe lunch, which seems to be the whole menu.

Vuong orders the signature salad, the enigmatic “vermicelli delight”, and the mushroom sizzler. I follow with the salad, and the dumplings — steamed instead of fried — wondering aloud if I will regret this (I will), and the kimchi stone bowl. We stick with tap water.

Menu

HanGawi

12 East 32nd St, New York

Mini prix fixe lunch x2 $70

— HanGawi salad x2

— Vermicelli delight

— Vegetable dumplings

— Mushroom sizzler in a hot plate

— Kimchi stone bowl rice

— Chocolate ice cream

Total (inc tax and service) $100.21

Family is at the centre of Vuong’s work, and his life. Readers and critics often conflate the two — particularly in the case of his novel. “I don’t think I could ever write a memoir. Because I like to imagine. Like, to me, everything starts with the autobiography. And then it has to be mythologised.” Vuong is also reticent to talk about his recovery from drug addiction. He feels he does not have the roadmap for sobriety. “I just say, it was like a car crash. And I’m still walking away from the car crash.”

Vuong was born in Vietnam. His maternal grandfather was an American soldier who returned to the US after the Vietnam war, leaving his grandmother and mother behind. His family fled as refugees in 1989, eventually landing in Hartford, Connecticut, where his mother worked in a nail salon.

A lacklustre student, Vuong attempted business school for a semester before dropping out and enrolling at City University of New York to study poetry. “I figured I could tell [my mother] it was anything,” he says. “I could tell her it was a law degree. I just wanted this piece of paper.”

Overhearing fellow university students laugh over a Shakespeare joke that he did not understand, “I felt so behind,” he says. So he caught up. “I was one of those people that read walking, read on the train. I read War and Peace on that two-hour journey from [the Queens neighbourhood] Flushing.” Learning to read — deep, critical reading — “felt like landing on shore”.

You basically think about how many people were involved in bringing this food here and that they have lives and names — it didn’t just come out of nowhere

Our salads arrive, and without fanfare Vuong presses his palms together, closes his eyes and utters a silent prayer. Blink and you would miss it. When I ask, he says it is a Buddhist invocation. “You basically just think about how many people were involved in bringing this food here and that they have lives and names, and it’s not just something that came out of nowhere,” he laughs. “I’m usually embarrassed to do it, it feels so precious.”

After his mother’s death, Vuong found solace in the Buddhist rituals of mourning, repeatedly dropping to the temple floor, prostrating himself in a deep, kneeling bow. “The pain you feel inside is mimetic now, with the pain outside. There’s a reason the ancients have been doing this for thousands of years,” he laughs. “Someone figured out that if you batter your knees, you’ll feel better.”

For Vuong, losing his mother has also profoundly rewritten the function of time. “There is only today, when my mother is not here, and yesterday, when she was . . . When I look at my life now, I just see it in two days.” Once grief fades, he says, “Now you have to negotiate memory.”

Vuong works as an associate professor at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, where he teaches poetry. Sometimes, he says, he finds himself dealing with difficult students and the thought occurs to him: “You’re going to lose your mother one day. And I start to feel for them, that checkpoint that they’re heading towards.”

Our salad bowls are cleared away and the second course arrives. Vuong starts on his vermicelli, unimpeded by the fear that consumes me as I realise my steamed dumplings are both enormous and structurally unsound. I begin to saw them in half with one side of a chopstick and silently accept that I might miss this course.

Time Is a Mother is a collection born of his grief, Vuong says, because it freed him. “Something strange happened when my mother died. I was just like, ‘fuck it’.”

Time Is a Mother is what happens “when all of myself is exhibited on the page”, he adds. His first books, he says, were austere, proving that he understood the canon and what he was supposed to do and deserved a seat at the table. Time Is a Mother has more pop culture, including lyrics from the late rapper Lil Peep. “I started a poem with the word ‘hey’. It took me 15 years,” Vuong says.

He is relinquishing some of that careful control in his poems, with “more tumbling and chaos”, more beauty. It is an act of rebellion in a language that dismisses the decorative. “What would it look like . . . if I say, ‘Guess what? I do value beauty?’ Because it’s medicinal to me. It’s not useless.”

Vuong is in New York full-time at the moment, as an artist-in-residence at New York University, where he earned his master of fine arts degree. He shows me a picture of his studio, piles of books, several pairs of shoes in the middle of the floor as if he’d absent-mindedly stepped out of them wandering towards his writing desk. “It’s such a cliché of an artist’s studio. It’s like, oh wow, that’s who I am if I didn’t have a family.”

The gravitational distraction of work keeps him from getting his driver’s licence too, he laughs. His younger brother is a good driver, he says, and so is Peter, Vuong’s partner of 15 years. Vuong can’t drive or fill out forms, but he loves to do the dishes. “I think that’s the secret to living together,” he says. “It’s just kind of knowing your limitations, and then filling the gaps for each other.”

Vuong is philosophical about the worlds he inhabits. When his cousin had a psychological breakdown and was arrested, it fell to Vuong, his family’s caretaker, to bail his cousin out of jail. “There are these curated spaces, like, here comes Ocean Vuong, with a bio and a whole programme . . . The week before, I was giving a reading at Harvard,” he says. “Then I’m having this Kafkaesque moment where I’m googling ‘how to bail’ as fast as possible.”

Our main courses arrive and my stone bowl is still sizzling from the heat, crisping the edges of the rice. Vuong’s lunch looks saucier, though, and I envy him. We reach forward and pluck lace-like cabbage kimchi from shared bowls.

Vuong has had to adjust in recent months to readers approaching him on the street, confessing pain or secrets, explaining the recognition they felt in his work. “I thought anonymity would be almost guaranteed in New York . . . I don’t own anything any more, I don’t possess myself,” he says.

He is wary of the trappings of literary celebrity, of being convinced that any of it — the readings, being published in The New Yorker, being known — means anything. “What’s helpful is being so out of it from the beginning, growing up answering phones in nail salons and being so forgotten and knowing how close that world is.”

I tell my students, ‘You’re sculpting language as much as you’re making it.’ What you don’t say says even more than what you say

He gestures to the street outside. There are five nail salons within a block of where we are eating. I had not noticed even one on my way there. Those artists with bowed heads, invisible to passers-by, are his heritage, Vuong says.

He is intrigued by the privacy achieved by the Pynchons and Salingers. He obsessively reads biographies of artists, trying to parse elemental detail about how they lived and how they wrote. I have just finished Frank Capra’s memoir, and say that what struck me most was that the Spanish flu — which almost killed the director and felled many of his barrack-mates in the army — was reduced to less than a page in the volume about his life.

“I always tell my students, ‘You’re sculpting language as much as you’re making it.’ What you don’t say says even more than what you say,” Vuong says. “It’s more traumatic that the paragraph is so short.”

Poetry has long been the language we use to discuss horrors that we cannot express any other way. Pictures from the invasion of Ukraine startle him for their familiarity, he says, the sameness of war from decade to decade. “War is a body next to a tank.”

Vuong is heralded for giving voice to the generational after-effects of war, its legacy and bitter strains that stay in the blood. He says: “When I was looking at the news, I just thought, who is the writer who is going to come out of this?”

His voice catches as he tells a story about Russian poet Anna Akhmatova, who describes in her work Requiem a time when she was asked by an older woman who, like Akhmatova, had a son in a Leningrad prison, “Can you describe this?” Akhmatova wrote: “I said: ‘I can.’”

Vuong swallows his emotion. “There are so many Akhmatovas coming out of that right now. And I can’t wait to meet them.”

Our plates are cleared away, and we are delighted by the dessert, a silky vegan chocolate ice cream. We are both lactose-intolerant, armed with enzyme pills that we won’t need today.

Vuong is preoccupied with the normalisation of violence in English. “You smashed it. You killed it,” he recites. In Vietnam, he says, “a country the size of California that has been at war for 2,000 years”, there is such awareness of death and violence that to speak of it is taboo. To say “death” is to invite it in. “We’re really perspicacious with that,” he says.

The US is a relatively new country, but its economic power and origin myth has been deceptive, and America does not consider itself young. “There’s an arrogance in that,” Vuong says. “It can’t look at Vietnam and recognise that Vietnam is so much more spiritually ahead in its customs because it went through so many cycles of war.”

The work of non-white writers can be used as a “tour bus” for white readers, he says, as well as for absolution when horrors strike that they are unprepared, or unwilling, to reckon with. After the 2021 spa shooting in Atlanta, where eight people including six women of Asian descent were murdered, Vuong’s agent called: his book sales were spiking. “Do you have any idea what it feels like to be relevant when Asian-American women are murdered?” he says. “Why do you have to read about our lives to feel like our lives are worth preserving?”

We linger after the bill is paid, and the conversation turns to his new home of Northampton, Massachusetts, and the Brimfield antiques market that takes place nearby a few times a year. Excited, Vuong pulls from his bag an antique leather artillery pouch, purchased at the market, that he now uses as a wallet.

Money, a small weapon to keep the dark corners of the world at bay. Vuong takes care of his family members now; he is the first one of them to earn more than $18,000 a year, he says. His 2019 MacArthur Fellowship, otherwise known as a Genius Grant, was a turning point. “It was like the bat signal to me. I knew, after that, that all of the problems would be taken care of at least financially,” he says. But he struggles with what he can’t help, frustrated that his mother died before he could take care of her.

We come back to language. Vuong is constantly aware of the contractions he is described in terms of — the “yets” and “despites” in between his adjectives. “Surprisingly eloquent despite his pre-teen frame,” is one he lays on our kimchi-flecked table. These contradictions puzzle him, the refusal to see him “as is”.

“In Vietnamese, ‘to make’ is the same as ‘to be’,” Vuong says. “One is not a son, one does son-ness . . . we have to work to earn our position in the world. Even in our family. To be a mother, to make a mother. Sometimes that makes more sense to me.”

Madison Darbyshire is the FT’s investment reporter in New York

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2022