This story was supported by the journalism non-profit the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.

Mondays are Access Esperanza’s busiest days. Some of the women who come seeking care may wait for a couple of hours but, CEO Patricio Gonzales said, “We do not turn away patients.” For his clients—most low-income and uninsured—waiting is worth it because the services are free.

Access Esperanza runs four family planning clinics serving roughly 15,000 patients a year in McAllen and nearby cities in the Rio Grande Valley where the average income is less than $20,000 per year. Gonzales said that for many of his patients, their yearly visit to one of his clinics may be the only time they even get their vitals checked. “We’re their only medical provider,” he said—it’s Access Esperanza or the emergency room.

In vast stretches of Texas, family planning clinics like Access Esperanza are a thin and threatened lifeline for low-income families. Getting any kind of healthcare can be difficult, especially in rural areas where the nearest hospital or clinic may be hours away and finding help to pay for it can be a nightmare. Until recently, patients could come in, fill out a relatively simple two-page application, and get care on the same day under a program called Healthy Texas Women (HTW). The program, which is the state’s largest safety net for reproductive healthcare, is a vital funding source for such clinics. It serves about 190,000 people a year.

In the past, clinic operators sent the applications off to the Texas Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC) in Austin and, usually within a couple of weeks, most were approved and the clinic was paid.

Not all the patients’ medical needs are covered by the program, but the basic screenings and exams save lives all the time—like the 55-year-old woman who came into Access Esperanza’s clinic in Mission “looking extremely pale, weak, and in need of a medical examination,” Gonzales said. Clinic workers determined she badly needed a blood transfusion and got her to a hospital ER. The next day, Gonzales got word that the clinic workers’ actions had saved the woman’s life.

But now the Healthy Texas Women program is unraveling, according to providers and healthcare advocates interviewed for this story.

In March 2021, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic and with little explanation to clinic operators, HHSC switched out the relatively simple HTW application for a 13-page application for Medicaid assistance. Things went downhill after that.

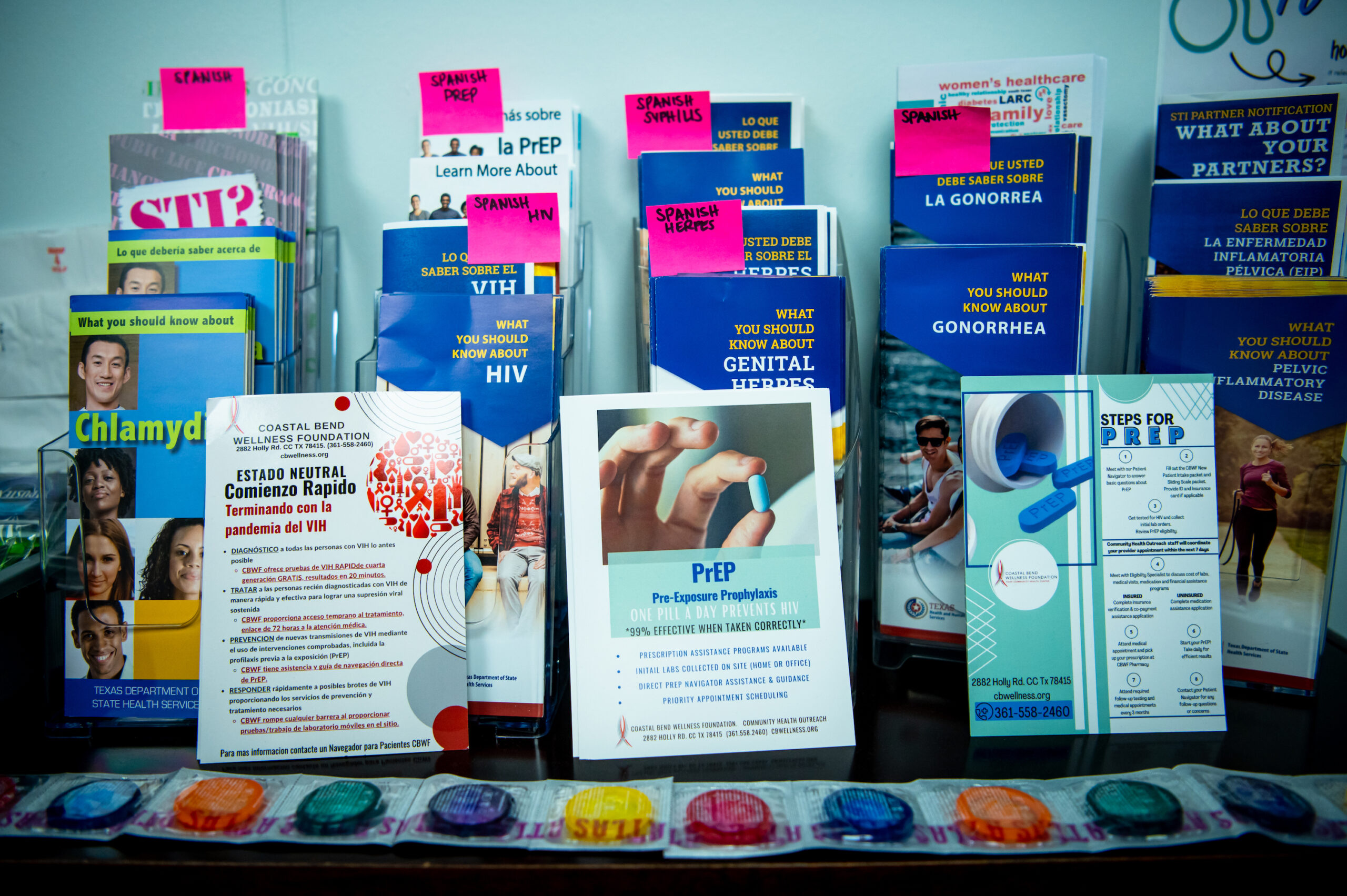

Family planning providers and others described the new paperwork as extremely complicated and, for many women, intimidating. As a result, they said, many applicants give up and go away, which probably means some will not get care anywhere else. Meanwhile, the health issues they bring to the clinics are often the kind that can’t wait. According to a state-generated report, the services most frequently sought by HTW applicants were treatment for gonorrhea and chlamydia or tests for pregnancy.

Gonzales said that, dating from the imposition of the new application, approvals of new HTW applications have ground to a near halt: Whereas most applications in the past were OK’d, now only about five out of every 100 are approved, he said.

That pattern has continued. Martha Zuniga, director of South Texas Family Planning, a nonprofit that operates six clinics in the Corpus Christi area, said that as of mid-February of this year, new HTW application approvals were down by 80-90 percent compared to that same time in 2021.

According to information provided by HHSC, in fiscal year 2020-21 application denials far outpaced approvals for women’s health programs in Texas—more than 461,000 were denied compared to about 292,000 approved and about 190,000 who actually received services.

There’s another problem: The speed at which HHSC either approves or denies applications has slowed tremendously. Whereas a turnaround of about two weeks had been standard, Zuniga said, some applications were still in limbo 45 or even 90 days after being filed.

That was a problem, Zuniga said, because such delays meant they couldn’t then bill that claim to another program. As a nonprofit with a mission to serve the uninsured and low-income population, she said, “We really do depend on those resources to work efficiently.”

In February, HHSC told Zuniga by email that until August 1 she will no longer have to hold pending HTW claims for 45 days before billing them to another funding source, the Family Planning Program. However, if Family Planning funding remains stagnant, this temporary reprieve won’t help much long-term.

The Family Planning Program, among other roles, acts as a fallback for clinics to get reimbursed for providing care to patients who can’t pay or whose bills don’t get paid by HTW or otherwise. When a patient’s claim under HTW is denied, clinics can roll the unpaid claim over to that program.

Clinics contract with the state to receive lump-sum Family Planning grants on an annual basis, but the grants haven’t increased to keep up with the rising needs of people seeking care. As a result of that and the problems with HTW, grants frequently run out before the end of the fiscal year, and yet clinics are required by law to continue providing care to patients. Clinic operators can file “funds gone” claims with the state—and then wait until sometime in the new fiscal year to be repaid, potentially adding months to the payment process.

“We’re going to see this program bottom out, I hate to say this, by May or June.”

All of this is threatening the financial viability of the family planning clinics that play a vital role in women’s healthcare in Texas. One provider said she already had to shut down one clinic last fall and suspend the operations of a second clinic temporarily.

Gonzales isn’t sure that the Healthy Texas Women program will make it through its current woes, and he knows that lives are at stake. “I think [we’re] going to see this program bottom out, I hate to say this, by May or June,” he said.

Christina Bonner, chief operating officer of Women’s & Men’s Health Services of Coastal Bend, also got the OK for her clinics, for the next several months, to roll over HTW claims to Family Planning without delay. She said HHSC leaders and legislators have stepped up their advocacy for added funding for Family Planning and are looking for other ways to help.

The clinics depend on HTW, and the lives of low-income Texas women depend on those clinics. People like Brigitte Pittman and Erica Garcia Ginnett owe their lives to safety-net programs. In the case of Ginnett, a 34-year-old college student and mother of two young girls, South Texas Family Planning clinics in Kingsville and Corpus Christi saved her life twice—once after an ER doctor had refused to treat her uncontrollable bleeding and more recently when she developed breast cancer.

On March 8, the Corpus Christi clinic received a gift basket with things like juice packs, Lifesavers and Peeps candy, and a letter from Ginnett. “All of you are my lifesavers. You are my Peeps!” it said. “I can’t thank y’all enough for my life because I might not have one if it weren’t for y’all.”

Stacey Pogue, a senior policy analyst at the nonprofit Every Texan, said that the clinics funded by the Family Planning Program (which also rely on Healthy Texas Women funding) “are the workhorses of the family planning network in Texas—they are the high-volume clinics, the long-standing clinics, they see a lot of people.” (Every Texan is the nonpartisan policy institute formerly known as the Center for Public Policy Priorities.)

Individual doctors make up the bulk of the practitioners who help provide reproductive healthcare to low-income Texans, Pogue said, but most reserve only a tiny fraction of their appointments for uninsured patients. Family planning clinics, on the other hand, serve low-income people almost exclusively.

To keep their doors open, the clinics rely on multiple funding streams: Healthy Texas Women, the Family Planning Program (which serves men and women), Breast and Cervical Cancer Services, and Title X, the federal program that provides affordable birth control and reproductive healthcare to low-income people. Each funding source is administered differently, and not all Texas clinics have access to the full range of funding. For patients without private insurance—the vast majority—clinics are required to screen first for Healthy Texas Women eligibility.

HTW patients can get annual exams, screenings for sexually transmitted infections, HIV testing, contraception, pregnancy testing, cancer screenings, and more. But when HTW applications are rejected or simply sit in the limbo of an HHSC backlog, the effect is to deny patients access to a program that has sufficient (mostly federal) funding and shove the costs of their care onto the underfunded Family Planning Program, thus increasing clinics’ financial woes. According to an HHSC report, the “funds gone” claims submitted by providers in fiscal year 2021 was $3.2 million—a figure that’s expected to rise.

For clinic operators, it has been a nail-biter. Waiting months for reimbursements can cause clinics to limit the number of birth control packs provided to patients; cut doctors’ hours; struggle to cover rent, utilities, and salaries; and ultimately, close either temporarily or for good.

For patients, moving claims to the Family Planning Program isn’t a great solution, Bonner said. “HTW as health insurance is much more useful to a patient than the Family Planning Program because with [FPP], it’s not like you get a card that you can take anywhere. Whereas your HTW card is like private insurance. You can take it to any HTW provider.”

In September, Kristén Ylana, executive director of the Texas Women’s Health Caucus, organized a roundtable discussion to address concerns about the Healthy Texas Women program. Twelve clinic leaders from all corners of the state—Beaumont to Amarillo, the Rio Grande Valley to Dallas—made the trip to meet with legislators and HHSC officials.

Over the summer, a lot had transpired. In June, the U.S. Supreme Court had overturned Roe v. Wade. Providers with HTW funding are not allowed to provide or pay for abortions, but the decision affected them nonetheless: In May, when news of the impending decision leaked, clinics began seeing more patients seeking contraceptive care, a trend that has continued.

Gonzales and other providers were baffled about why the application had changed, when the simpler version was easier for both patients and staff. The reason, they learned, had to do with something called an 1115 Demonstration Waiver, submitted by Governor Greg Abbott in 2017 to turn HTW into a Medicaid-funded program. The simple application had been negotiated away when the waiver was finally approved in January 2020.

According to HHSC Press Officer Tiffany Young, it was the federal agency that oversees Medicaid that forced the change in the application. Young said the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) insisted, as part of the waiver negotiations, that the new HTW application capture information needed to determine a number called MAGI—the patient’s Modified Adjusted Gross Income.

Instead of basic income questions, applicants are asked to calculate the amount of their “pretax contributions per pay period, how often contributions are made, as well as the date contributed” for all members of their household.

The tone of the form shifted as well, stressing that the patient is signing “under the penalty of perjury” and that HHSC checks answers against “electronic databases and databases from the International Revenue Service (IRS), Social Security, the Department of Homeland Security, and/or a consumer reporting agency.”

If patients or their household members work informally at jobs where they don’t have to file income tax withholding forms, they’re at a disadvantage. So are people who work multiple jobs or who may have a hard time tracking down former employers for verification. If family members have clouded immigration status, patients may decide that completing the application is too much of a risk.

Providers noticed another issue: The 13-page application didn’t provide protection for victims of domestic abuse. On the simpler form, joint insurance information (with a parent or spouse) could be waived if the applicant was a victim of abuse, as are about 20 to 25 percent of patients seeking family planning care.

According to a CMS spokesperson, states can use a separate application for family planning coverage. But Texas chose to use the same application it uses for other Medicaid programs.

To complicate matters more, during HHSC’s negotiations with CMS a feature called “adjunctive eligibility” was stripped away. In the past, people who had already qualified for other income-tested programs—like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, or the Women, Infants, and Children supplemental nutrition program—automatically qualified for HTW. Now, however, they must submit the same documentation all over again.

The Healthy Texas Women program website is confusing. The “How to Apply” section says that applying for services is “easy” but also notes that the online application “works on desktop computers, but not on mobile phones or tablets”—a challenge for people who don’t have access to a computer or the internet.

Patients can download the form and print it instead, but that requires access to a printer. It also assumes they were able to find the form in the first place—there is no form labeled “Healthy Texas Women.” Instead, it is listed under “Medicaid or CHIP, form H1205” (the 13-page version) or form H1010 (the 33-page version for HTW only).

Providers seldom know why applications for HTW coverage are denied. Patients themselves get denial letters, but those may provide little information. In one case, a patient returned to share her letter with Access Esperanza. The letter didn’t list a reason, just six-digit codes. While at the clinic, the woman called HHSC to ask for clarification, Gonzales said, “but the wait time was over an hour, and she couldn’t complete the call.” A recording suggested she fill out the application all over again.

Clinic staffers help patients with applications, but extra visits to the clinic can be a struggle themselves, requiring childcare arrangements, time off from work, and reliable transportation. So clinic operators do their best to make healthcare a one-stop task. Bonner, of Women’s & Men’s Health Services of Coastal Bend, said her clinics offer gas cards and bus passes. Thanks to onsite pharmacies, women don’t have to make a return trip to get birth control supplies or to have IUDs inserted.

Gonzales said that when people first see the 13-page HTW form, their eyes widen. It takes patients as long as two hours to complete, pushing the overall visit time to four hours or more. “Sometimes people get so frustrated they leave.”

Peggy Smith sees the same problem among the 13- to 24-year-old students she serves as CEO of Teen Health Clinics, a program run by Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. She said the application process for HTW coverage is incomprehensible and intimidating to young patients who are usually seeking birth control or STI treatment and who seldom have the family income information needed for the HTW form. That pushes their care costs onto the clinic’s Family Planning Program grant. When that money, as a result, ran out too quickly, Smith was forced to close one clinic and pause operations at another last fall. Three of her clinics are located in inner-city high schools where few students have primary care doctors. Those schools are safety nets for such kids, she said, and also their “medical homes.”

Brigitte Pittman didn’t have a “medical home” until she found out about HTW, when she was more than a year into postpartum depression.

At the private Christian high school she attended in the Dallas area, Pittman said, abstinence was the only sex education taught. She was a college student before she learned about sexually transmitted diseases and birth control. Stephenville, in Erath County southwest of Fort Worth, where she went to college and still lives, has about 42,000 people, but according to the nonprofit group Power to Decide, not one publicly funded health center with a full range of contraceptive options is available. The group lists Erath County as a contraceptive desert.

Pittman was in her mid-30s—and the mom of three boys—before a friend told her about the Healthy Texas Women program. Pittman said the enrollment process was frustrating and difficult (she couldn’t find the short form online). But she got approved in 2017, kept up her eligibility by resubmitting information on her husband’s income every few months, and says HTW saved her life.

By 2017, Pittman had been without comprehensive healthcare for years, sometimes ending up in the emergency room “because I waited so long to seek help.” Her last pregnancy had been deemed high-risk: Her gestational diabetes had turned into long-term diabetes and her postpartum anxiety had hung on. The dangers of another pregnancy have made her “highly uncomfortable [about] ever having more kids.”

Pittman said HTW gave her access to essential services such as birth control, annual exams, diabetes screenings and, finally, treatment for depression and anxiety. Now a single mom, she works from home for a company she likes and is training for a new position. Working from home gives her more time with her boys—a 12-year-old and 9-year-old twins.

Pittman was nervous and excited in February when she spoke in front of the Capitol for the first Texas Women’s Healthcare Coalition Advocacy Day. “I know that it”—HTW saving her life—“sounds like a stretch to say right now,” she told the audience. “I was in such a dark place.”

In October 2022, HHSC Deputy Executive Commissioner Wayne Salter told a Texas House panel on healthcare reform that 400 staff vacancies at his agency had led to a backlog of 70,000 Medicaid applications over 45 days old. By mid-February of this year, according to HHSC, that backlog had grown to 159,860 applications.

Also in February, Young, the HHSC press officer, said there is “currently no backlog for HTW-only applications. However, if an individual applies for HTW and other programs or Medicaid and other programs, HHSC must first assess eligibility for Medicaid programs before determining eligibility for HTW. There currently is a backlog for these types of applications.”

“Providers like us are the backbone for the uninsured and low-income. … We are where they come and who they trust.”

When the Texas Observer asked for clarification about HTW-only applications, Young pointed to form H1010, by which a patient can agree to forego other benefits and just apply for HTW. That would be faster, right? Apparently not. Young noted that Texas still requires all applications to go through a tiered screening system that checks patients for eligibility for Medicaid and another program as well as HTW. In short, there is no fast track for individuals just seeking help with birth control and STI screenings.

Zuniga of South Texas Family Planning pointed out that if HHSC was behind in processing applications, it would have been helpful for providers to know earlier. “Providers like us are the backbone for the uninsured and low-income,” she said. “We are where they come and who they trust.”

Another bureaucratic threat is also about to hit the family clinics and their patients. The pandemic-related federal waiver that had extended Medicaid coverage for about 2.7 million Texans—mostly children and mothers—expired on March 31. HHSC has now begun a federally required review of the state’s entire Medicaid rolls, about 5.9 million people. Advocates fear that the health agency, already dealing with staff shortages and application backlogs, may be overwhelmed by the task.

If the path to family planning healthcare in Texas seems filled with potholes, it’s partly because the route goes through the battlefield of abortion.

Many of the holes in the healthcare coverage system for women in this state were once filled by Planned Parenthood health centers. But Republican state leaders fought a long and ultimately successful legal battle to bar Planned Parenthood—and any other organization associated with abortion—from receiving state-managed healthcare funds in Texas.

In 2011, the state cut funding for family planning programs from $111 million to less than $38 million. When Texas asked the Obama administration for a waiver that year to allow its Medicaid-funded programs to bar abortion providers from participating, the request was denied.

The Trump administration had no problem with the state excluding any abortion provider (or its non-abortion-providing affiliates) from Medicaid funding and approved the waiver. Before the Texas Legislature went after their funding, Planned Parenthood health centers “provided care to more than 40 percent of Texas’ Medicaid women’s health program patients,” said Sarah Wheat, chief external affairs officer at Planned Parenthood. Texas policies on women’s healthcare now are “a mess with lots of detours and roadblocks,” she said.

The waiver that denied funding to Planned Parenthood clinics will expire at the end of 2024. HHSC officials plan to seek a renewal. But Texas’ justification for banning an organization that no longer provides abortions in the state is wearing thin.

Some clinic operators and women’s health advocates see glimmers of hope for Texas’ family planning clinics and the Healthy Texas Women program.

Pogue, for instance, is optimistic about legislation that would increase access to care: Senate Bill 807 would require health insurers to give patients the option of receiving 12 months of birth control supplies at one time. House Bill 141 would make contraception available through the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). Texas is one of only two states that don’t do that now, even though the program covers young people up to age 18 and part of their 19th year.

Kristen Lenau, health policy director with the Texas Women’s Healthcare Coalition, pointed out that the basic state budget proposal for the next two years includes $87 million—a 25 percent increase—for women’s healthcare programs.

Smith, CEO of Teen Health Clinics in Houston, is hoping Texas will adopt a fast-track application for young patients. She knows of two states, Oregon and Mississippi, that use a two-page form that’s simple enough for underserved youth to fill out.

Bonner is hopeful that the proposed increase in funding for the Family Planning Program and possible midyear allocation to the program will help close her clinics’ funding shortfall created by Healthy Texas Women’s bureaucratic challenges.

“The new 13-page HTW application is an outrageous barrier to care when you consider how limited the services it provides are, but HHSC is assisting providers in finding ways to work around it,” Bonner said.

A year ago, it seemed unlikely that Erica Garcia Ginnett would live long enough to watch her kids grow up.

Ginnett is a journalism student at Texas A&M University-Kingsville who’s also active in theater. Her daughters are now 8 and 12. She was rehearsing a play in March 2022 when another actor shoved her during a scene. As she pushed back, she felt a sudden loss of blood that soaked her pants. She’d been experiencing uncontrolled vaginal bleeding that had worsened over the course of a year, but this was urgent. Her husband, an EMT, was there and rushed her to the ER, where the doctor confirmed what the couple already suspected: Ginnett had a prolapsed uterus. She was prescribed birth control to help slow the bleeding, but a couple days later she lost consciousness after stepping out of the shower. That led to another ER visit, at which she saw a different doctor—or actually, he refused to see her, saying that someone so young couldn’t possibly have a prolapsed uterus.

A concerned nurse practitioner encouraged Ginnett to go to another location where the practitioner worked, the local South Texas Family Planning Clinic. There, the nurse practitioner examined her, confirmed the prolapsed uterus, and prescribed a different birth control and a Depo-Provera shot to get the bleeding under control. And clinic staff helped her sign up for Healthy Texas Women coverage.

It was wonderful, Ginnett said, to find “organizations that are there to help people who don’t know the system, don’t know what routes you have to take, what forms you have to fill out … and they say, ‘Come sit in my office and let’s work on this together.’”

Ginnett and her husband couldn’t afford health insurance through his employer; the $800 biweekly premiums would have eaten most of his paycheck. Their kids are on CHIP. She had tried earlier for Medicaid benefits but was only approved for them during her pregnancies. Without continuing Medicaid help, she had lost her regular OB-GYN care.

In September, Ginnett found a lump in her left breast. The nurse practitioner at South Texas Family Planning recommended she get it checked out. When doctors found that the lump was cancerous and recommended a partial mastectomy, the clinic staff helped her to enroll in the Medicaid for Breast and Cervical Cancer program. Two months later she had a partial mastectomy. Unfortunately, because her cancer was estrogen driven, she had to stop taking birth control, which brought back the uncontrollable bleeding and led to anemia. She was grateful that her Medicaid policy covered a full hysterectomy in February.

She’s about to head into five years of chemotherapy, just as the unwinding of Medicaid in Texas begins. She’s less concerned about losing coverage herself—she’s been assured she won’t—than about her kids who need to stay on CHIP for their medications.

“It’s the difference between getting to see your kids graduate from high school or not.”

When Ginnett was able to begin seeing a gynecologist regularly through Medicaid for Breast and Cervical Cancer, she finally learned that the bleeding had been caused by a large fibroid tumor in her uterus, which was found after her hysterectomy. When she dropped off the gift basket at the South Texas clinic’s Corpus Christi location, Ginnett hugged the staff member who accepted it and cried.

Ginnett said she hopes that people looking for healthcare won’t get discouraged.

“You’re going to get a lot of ‘No’s’ when you’re searching for something, but when you finally get the ‘Yes, I can help you,’ the ‘Yes, I know what we need to do,’ it’s worth it,” she said. “Because it means your life. It’s the difference between getting to see your kids graduate from high school or not.”