Kamila Valieva isn’t the first young athlete accused of doping at the Olympics, and she surely won’t be the last unless we start taking the special circumstances of youth athletes seriously.

Concerns about youth doping were amplified at the 2022 Olympic Winter Games in Beijing following the news that Valieva, a 15-year-old Russian figure skater, had tested positive for the banned substance trimetazidine. The delayed news of her positive test raised many questions, including whether it is time to add minimum age limits to Olympic participation.

Age limits at the Olympics are set by each International Federations (IF) — the international sports bodies that govern individual sports — and not by the International Olympic Committee. Specifically, Rule 42 of the Olympic Charter states: “There may be no age limit for competitors in the Olympic Games other than as prescribed in the competition rules of an IF as approved by the IOC Executive Board.”

Just like the IOC does for sex testing, eligibility rules for age are deferred to the IFs. Some IFs have decided that age matters, and imposed minimum age restrictions for Olympic participation — others have not. These range from 13 for fencing and 14 for taekwondo and bobsled, to 17 for wrestling, cycling and weightlifting, and 20 for the marathon.

How young is too young?

Many people believe Valieva is too young to have doped without adult involvement. But there is no “too young” to commit a doping offense. For example, a 12-year-old Polish boy tested positive for nikethamide and received a two-year ban from the Federation Internationale de L'Automobile. His lawyer argued he should not be sanctioned because he was too young to compete at the Youth Olympic Games (YOG). Despite his age, and the banned substance being traced to an energy bar, the Court of Arbitration for Sport only reduced his ban by six months, noting he was not too young for the anti-doping rules to apply.

At the inaugural YOG, two 17-year-old wrestlers failed doping tests and were required to forfeit their participation certificates and any medals won. Both were suspended from the sport for two years, and their names were entered into the public doping registry of the IF (now known as United World Wresting), despite their legal status as minors.

Two more examples illustrate that age does not protect an athlete from the consequences of doping at the Olympics. At the 1972 Summer Games, 16-year-old swimmer Rick DeMont of the United States lost his gold medal in the 400-metre freestyle when he tested positive for ephedrine. All involved in the case understood that the ephedrine was part of his prescription asthma medication. His team physician failed to disclose the athlete’s required use of the medication, yet the disqualification stood.

Sixteen-year-old Romanian gymnast Andreea Răducan was in the same boat at the Sydney 2000 Olympics, when a cold tablet given to her by her team physician contained a banned substance. Jacques Rogge, who was appointed president of the IOC a year later, acknowledged to reporters the injustice of the situation: “This is one of the worst experiences I have had in my Olympic life.”

The Olympic movement has long held the position that doping rules are firm. What’s different now is the increased awareness of athlete mental health, the role of the entourage and the risks associated with overtraining and specialization at a young age. The range of reactions to Valieva’s saga, from Tara Lipinski’s outrage to Katarina Witt’s compassion, highlights the need to consider different models of youth participation.

Age limits for athletes: yay or nay?

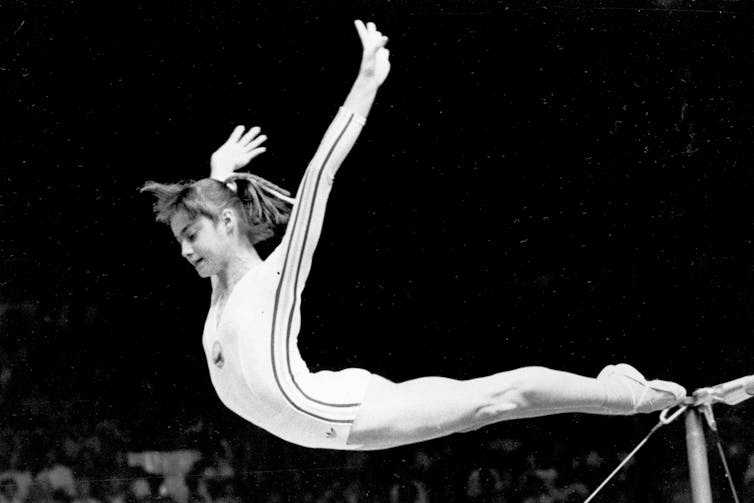

Banning young athletes from the Olympics would mean we miss spectacular performances like Chinese diver Fu Mingxia’s gold in the 10-metre platform diving at the Barcelona 1992 Olympics at age 13, and Romanian gymnast Nadia Comaneci’s perfect 10 at the 1976 Montreal Olympics at age 14.

But considering all we know about overtraining, exploitation and abuse in sport, that might not be a bad thing.

Protection-based age limits are unlikely to be effective. Youth who are ineligible to compete at the Olympics can still train the same number of hours as their older, eligible competitors.

Solutions must recognize that child athletes are the most vulnerable population affected by doping and, legally, have not developed the capacity to make rational, independent decisions. As the history and philosophy of childhood literature establishes, the division between childhood and adulthood, and the time in between, is hard to categorize and is culturally conditioned.

The inclusion of a protected persons category in the 2021 update to the World Anti-Doping Code is a step forward.

WADA now acknowledges protected persons as athletes who are under 16 years (or under 18 if the athlete is not part of a registered testing pool or has not competed at international events) or are otherwise not legally competent. The code states that mandatory public disclosure is not required when a protected person commits an anti-doping rule violation, but it does not go so far as to prohibit media reporting on the athlete. What this means in practice is unclear.

Many questions remain about why Valieva was permitted to continue competing, and more debate about what we owe “protected people” is needed.

Sarah Teetzel ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.