Mukund Padmanabhan’s engrossing The Great Flap of 1942 tells of a series of events triggered, ironically, by a non-event. During World War II, as the British panicked over the possibility of a Japanese invasion of India, lives were disrupted, cities abandoned, and much chaos unleashed. In an email interview, Padmanabhan talks about this strange, surreal episode in Indian — and military — history.

The book originates with a personal story. Your mother had to interrupt her studies and move inland when fear of a Japanese invasion was at its peak. What was the human and emotional cost of the whole affair?

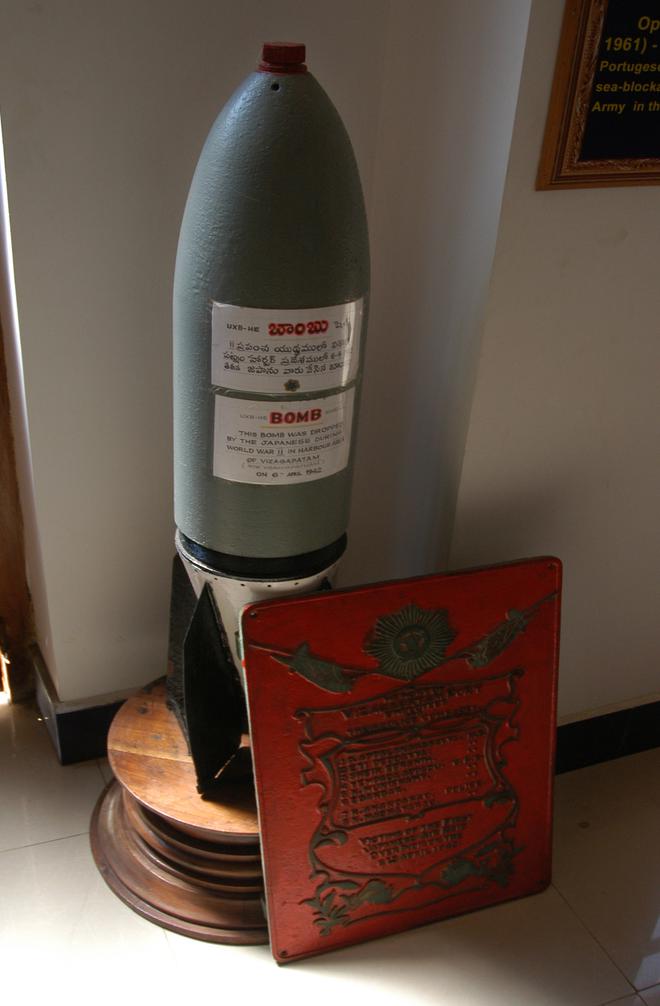

I live in Madras, where almost everyone I know has a story about a family member who fled the city. Conservatively, 75% of the population left, but there are reasons to believe the number could have been almost 90%. But it wasn’t just Madras or Visakhapatnam (which was bombed and emptied out). People fled Calcutta and Bombay, and there was fear and migration even from unlikely interior places such as Delhi, Ahmedabad, Jamshedpur and Kodaikanal.

Unlike Partition, this exodus has been largely unmapped. Also, the book reveals that the Raj coldly encouraged people it deemed “non-essential” or “useless mouths” to flee because it felt that cities with a reduced population would be easier to manage in the circumstances. They treated the exodus like a managerial problem — one of getting “inessentials” to leave while retaining those engaged in vital services, including the production of war material.

The question you raise about the human and emotional cost is interesting. One can understand our colonial rulers and the British-owned press not caring about the plight of those who fled. But surprisingly there was not much discussion even in the nationalist quarter. There is little beyond bland matter-of-fact single-columns in the Indian-owned newspapers — a reminder that the culture of reporting human interest stories, those that necessarily go beyond official statements, is something that developed much later.

Even today, the Japanese threat to India is a little known element in the country’s experience of World War II. How serious was this threat, and how far was it a consequence of British paranoia?

We now know that Japan had no intention of invading India in 1942. So in truth, there was no real threat. All Japan wanted was to create disruption, foster anti-British sentiment, and create an impression that Britain was incapable of defending India. This it did very effectively through sporadic air raids and sustained propaganda.

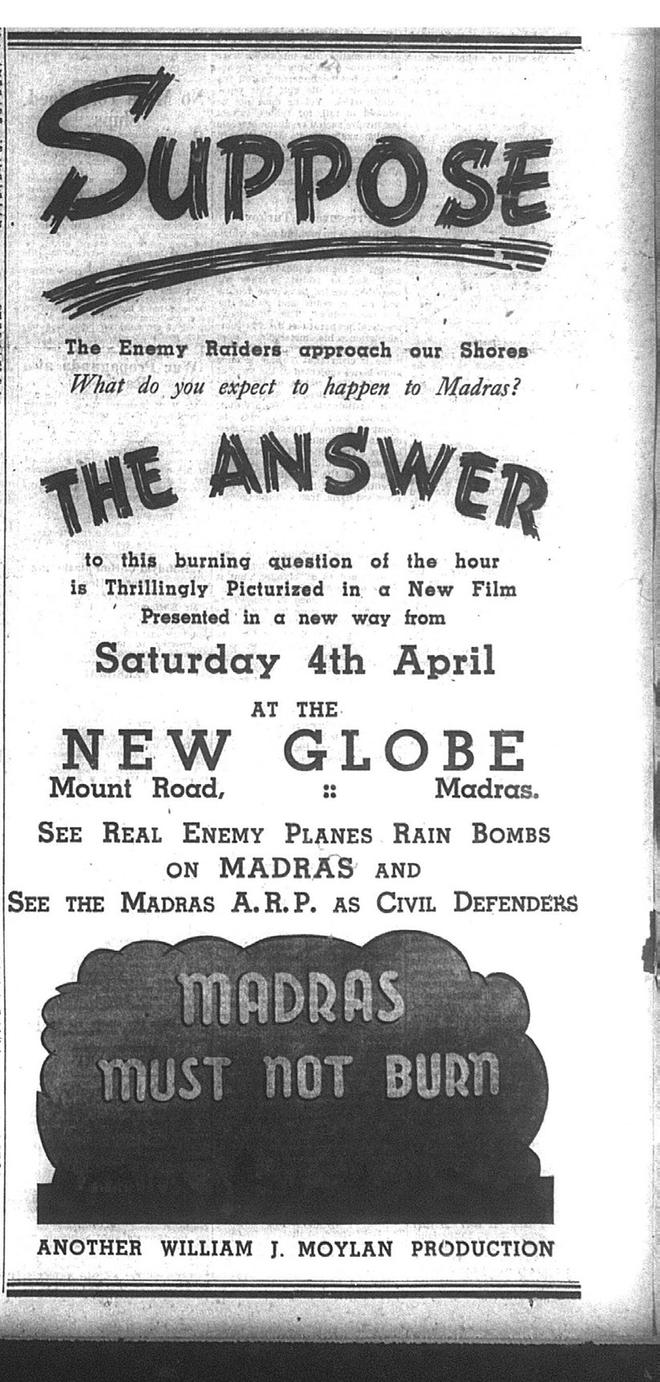

Even if there was no real threat, the Indian government — to be fair — had to prepare for the possibility, however remote, of a Japanese attack. So there was justification for some steps the administration took — from strengthening India’s defence capability to implementing certain Air Raid Precaution (ARP) measures.

But at the same time, other government actions unnecessarily heightened the panic and led to the misconception of an imminent invasion. This included putting out mixed and confused messaging about Japanese intent, encouraging “non-essentials” to flee, and relying on false military intelligence that spoke of a Japanese fleet about to make landfall south of Madras in mid-April 1942. I guess one could argue that there was a touch of paranoia about all this.

As you show, fear of the Japanese affected much of the subcontinent. We also discover mixed responses of the British government. Do tell us more about the wider impact.

When I began work on the book, I assumed it would be mainly about Madras. But the research called for a larger story — one that was pan-Indian and demanded a wider narrative arc starting with Japan’s attack on Malaya and its military successes in Southeast Asia. Also, the book attempts to analyse how World War II shaped Britain’s attitudes to India as well as the impact it had on the nationalist movement. After all, the major political events of 1942 — the Cripps Mission and the developments that led to the call to Quit India — took place against the shadow of the Japanese threat. The book examines these events against the context of Japan’s military ascension. The British were divided about how much to offer the Congress in return for supporting the war effort.

How did the nationalist movement grapple with the issue? Gandhi, for instance.

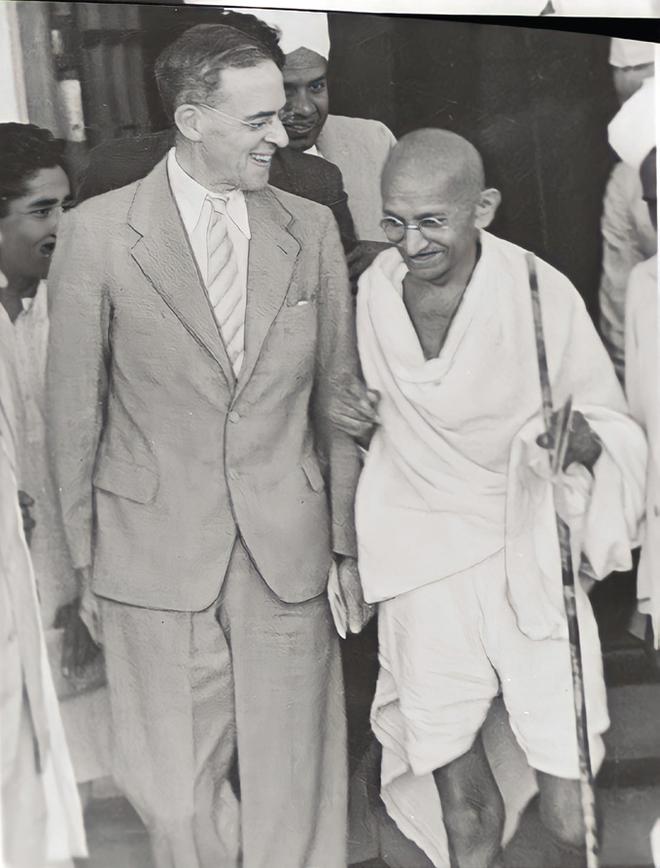

The war in general, and in particular Japan’s entry at the end of 1941, divided the Congress. We know that Gandhi’s unswerving commitment to non-violence seemed absolutist and unreal to many Congressmen. He was opposed to India getting involved in the war whereas some of his colleagues believed it politic to offer conditional support to a beleaguered Britain in exchange for self-government, if not a promise of freedom.

Gandhi continued to maintain this position even after fears emerged that Japan would invade India. Inevitably, this led to unfair accusations that he was pro-Japan. But it is true that his commitment to non-violence blurred ideological differences and deflected attention from the significance of happenings abroad. For Gandhi, the moral distinction between aggression and counter-aggression was, at best, a very fine one. He wrote repeatedly that the best recourse in the face of aggression is passive resistance or non-cooperation.

Gandhi also appeared to believe, as did many Indians in 1942, that Japan and the Axis powers might win the war. I suggest that it is, at the very least, worth asking whether such a belief had a bearing on the rejection of the Cripps offer and the sudden emergence of what one historian described as his “strange and uniquely militant mood” that culminated in the Quit India call.

The book is peppered with small details, not all pleasant. The murder of animals in the Madras Zoo, for instance. Was there something that startled you?

The main thing that interested me in this story was that many events — including the shooting of ‘dangerous’ animals, the panic, the rumours — were a result of something that never actually happened: a Japanese invasion. This lends a quirky, somewhat dystopian twist to the narrative. I did ferret out some odd, eccentric stories. I was delighted, for instance, to learn about poet W.H. Auden’s brother concocting a cheap tarry substance and conducting an experiment to see whether it would produce smoke profuse enough to obscure Delhi’s South Block from enemy aircraft. All this, at a time when there was absolutely zero risk of Delhi being bombed. The nearest Japanese airbase was simply too far away.

The Great Flap of 1942; Mukund Padmanabhan, Vintage, ₹599.

The interviewer is a historian.