In an ever-more uncertain world, one thing you can say with a degree of confidence is that, right now in global affairs, all roads lead to Donald Trump. Trump’s re-election to the US presidency – while widely anticipated (especially by the bookmakers) – has kicked off something of a chain reaction.

Whether it’s his track record in his first term in office from 2017 to 2021, comments he made on the campaign trail, comments he has made since the election, his cabinet picks or comments his cabinet picks have made, the prospect of Trump assuming arguably the most powerful office in world politics in just a few weeks time is making its own weather around the globe.

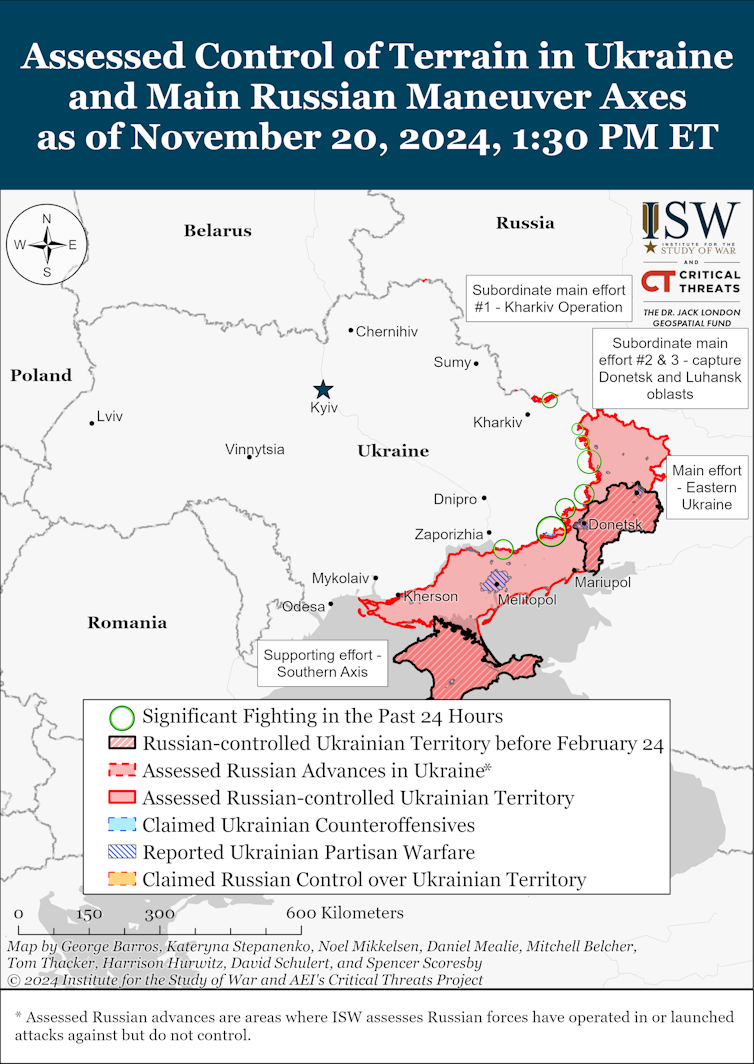

In Ukraine, where the war has just passed its 1,000th day and Russia continued to advance slowly but steadily, the prospect that next year will see a ceasefire brokered by the Trump administration, followed by negotiations at which Vladimir Putin would hold many of the cards, looks to be the new reality.

The idea, cherished by Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelensky, that Ukraine’s defenders would be able to force Russian troops back beyond the borders as established at the end of the cold war in 1991 – a notion in which he was wholeheartedly supported by his western allies – now appears to be a non-starter. All indications point to a frozen conflict, with each side holding the territory it now occupies (although one can imagine Ukraine will have more of a problem holding on to the 600 or so square kilometres of Russian soil it presently controls in the Kursk region).

Now, more than ever, it’s vital to be informed about the important issues affecting global stability. Sign up to receive our weekly World Affairs briefing from the UK newsletter. Every Thursday we’ll you expert analysis of the big stories making international headlines.

But, of course, there was already a frozen conflict in eastern Ukraine after Russia’s incursions in 2014. And – as Stefan Wolff, an international security expert from the University of Birmingham, points out – the Minsk accords on Ukraine of September 2014 and February 2015, which were supposed to maintain some degree, at least, of security and stop the fighting in the region turned out not to be worth the paper they were written on.

There’s very little chance that Trump will allow US troops to be sent to Ukraine as peacekeepers or combatants. So, Wolff surmises, it’ll be down to Europe to step up. The Polish prime minister, Donald Tusk, said as much before the US election and Margus Tsahkna, Estonia’s foreign minister, has explicitly said this week that Europe must be prepared to underpin a peace deal.

Europe must ensure it is intimately involved in any peace negotiations, Wolff concludes: “In negotiations involving Trump, Putin and Zelensky alone, Ukraine would be the weakest link and European interests would probably be completely ignored… After 1,000 days of the most devastating military confrontation on European soil since the second world war, it is time to accept that nothing about Europe should be without Europe.”

As you might expect, Trump’s victory has also been focusing the mind of the man who is currently sitting behind the Resolute desk. And on day 998 of the conflict, Joe Biden, gave Zelensky the go-ahead to use US-supplied long-range Atacms (army tactical missile system) against targets inside Russia, something the Ukrainian president has been begging for over pretty much the duration of the war.

Ukraine immediately took Biden at his word, launching eight missiles at targets in Bryansk, a Russian region bordering Ukraine. The following day the UK government formally signed off on Ukraine using its Storm Shadow long-range missiles in the same way, and Ukraine used them to attack targets in the Kursk region.

Many commentators believe that one of the epitaphs for Biden’s handling of the war in Ukraine will be too little, too late. This week he also gave permission for Ukraine to deploy anti-personnel mines (APLs) in Ukraine, of the sort that are shunned by 164 countries that are signatories to the Ottawa convention banning such ordnance. Which, of course, means he might have another epitaph as the US leader willing to use weapons almost universally condemned as a horrific scourge “already contaminating more than 70 countries”.

It’s worth noting, though, that neither the US nor Russia is a signatory to the convention. Ukraine is – but that hasn’t prevented it becoming one of the most mine-contaminated countries in the world.

The reason that Ukraine is so keen to get their hands on these APLs, writes David Galbreath of the University of Bath, an expert in military technology, is that it needs to find a way to stall Russian infantry as they continue to advance.

Galbreath describes how the success of Ukrainian drones at targeting Russian armoured vehicles had forced the Russians to change tactics and advance on foot. Ukraine had been finding their anti-tank weapons ineffective for forcing enemy infantry into their lines of fire, hence the need for anti-personnel mines, no matter how dirty a weapon they might be.

On Putin’s side of the ledger, meanwhile, the main issue is that Russia’s advantage in the field has always depended on the asymmetric advantage provided by the imbalance in troops numbers. Put simply, the Russian military has always been able to call on more bodies to throw into battle than Ukraine.

But there are suggestions that Putin’s reservoir of manpower might be shallower than he’d like. His decision to deploy North Korean troops in the Kursk region, the emptying of prisons to send convicts to the frontline and, more recently, the recruitment and training of troops from the occupied parts of Ukraine all hint that filling Russia’s quota of 20,000 new troops each month has not been plain sailing.

Natasha Lindsteadt, an expert in authoritarian regimes from the University of Essex, gives us an in-depth look at how Russia fills its ranks. She surmises that, just quietly, Putin might be as keen as Donald Trump to bring this conflict to a speedy conclusion: as long as it favours his side, of course. Because Putin is quickly running out of people he can send to the front lines.

Read more: Russia needs a peace deal soon as it is running out of soldiers

The view from Israel

Back in Washington, Trump’s senior foreign policy choices are coming in for a degree of bemused scrutiny. Israel’s prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, will be considerably buoyed by the news that Trump wants former Arkansas governor Mike Huckabee as his ambassador to Israel.

Huckabee, whose CV also acknowledges his stint as a talk-show host, an evangelical Baptist minister and contender for the Republican presidential nomination in 2008 and 2016 (when Huckabee called the president-elect a “car wreck”), is known for his outspoken views on Palestine. Namely that it doesn’t exist.

Huckabee is on the record for saying, after witnessing the inauguration of n illegal settlement on the West Bank, that: “There is no such thing as a West Bank. It’s Judea and Samaria [the territory’s biblical name]. There’s no such thing as a settlement. They’re communities, they’re neighbourhoods, they’re cities. There’s no such thing as an occupation.”

Clive Jones, a professor of regional security at Durham University with a particular interest in the Middle East, believes that Trump could take the brakes off Israel’s campaign in Gaza, the West Bank, Lebanon and even against Iran.

While Joe Biden has maintained steadfast support for Israel and the government of its prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, he has privately urged caution. He recently attempted to put a deadline on Israel ensuring more food and humanitarian supplies get into Gaza where people are starving.

But, as Jones notes here, Trump’s pick for secretary of state, Marco Rubio, while mainly known as a China hawk, is on the record as being against a ceasefire in Gaza. He told journalists recently that: “I want them [Israel] to destroy every element of Hamas they can get their hands on. These people are vicious animals who did horrifying crimes.”

With elements of Netanyhu’s government urging the annexation of the West Bank and signs that they might also have designs on northern Gaza and a US administration that looks set to back Israel to the hilt, things are looking bleak for the Palestinian people, concludes Jones.

There has been a major personnel change in Netanyahu’s cabinet, too. Earlier this month he unceremoniously dumped his defence minister, Yoav Gallant. If Biden attempted to be a brake on Netanyahu from the White House, perhaps Gallant was the nearest thing to someone attempting to moderate the behaviour of the prime minister from within his own government.

Gallant has long called for a ceasefire and a hostage deal. He also wanted universal conscription and an end to the exemption of ultra-Orthodox men from military service. And, perhaps, most significantly, his was a strong voice calling for an immediate state inquiry into the causes of the October 7 Hamas-led attacks – something his critics say he is desperate to avoid.

John Strawson, of the University of East London, who writes regularly about Israeli politics here, believes that Netanyahu might act against other powerful military voices in the weeks to come. He believes that the Israeli prime minister is “to reshape Israel in his own political image. That means not only diminishing the role of the judiciary, but also undermining the influence of the IDF and the security establishment.”

In what appears a sinister corollary to Gallant’s dismissal and the appointment of Huckabee as US ambassador to Israel, Netanyahu has nominated a far-right firebrand, Yechiel Leiter, as the new Israeli ambassador to Washington. Leichter, who came up via the now outlawed Kahanist movement in the US, is known to favour annexation of the West Bank.

He’ll soon be back in America sharing his vision with the Trump administration.

World affairs briefing, from the UK is available as a weekly email newsletter. Click here to get our updates directly in your inbox.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.