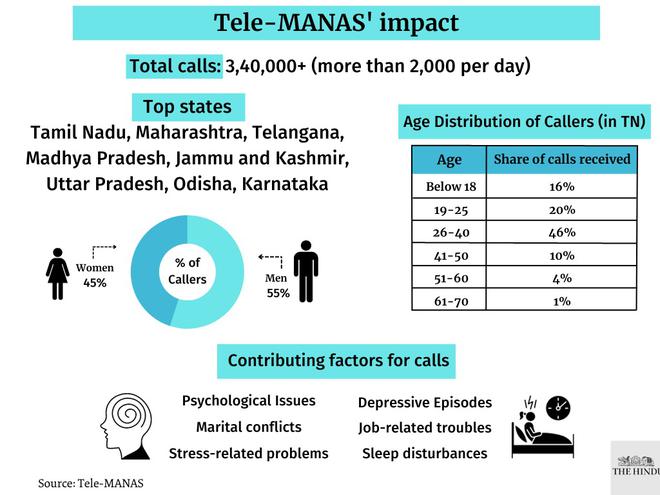

The numbers 14416 and 18008914416, over the last year, have built a route to mental care. A brief ringing tone digitally escorts the caller around Tele-MANAS, India’s round-the-clock mental health helpline. The caller is asked to select a language of their choice among 20 options, then led to a trained professional. The line transmits their stress, anxiety and grief; some concerns demand emergency attention, others need prolonged care. Since its launch in 2022, Tele-MANAS has received over 3,40,000 calls (as of October 8) from 51 cells spread across 32 States and Union Territories, now fielding more than 2,000 calls per day.

The helpline was a response to a mental health crisis inflamed by the COVID-19 pandemic: isolation, financial precarity and illness adversely impacted levels of anxiety, depression and substance use disorders globally. Estimates show that 70-92% of Indians do not receive medication or treatment for different mental conditions. Tele-MANAS was thus envisioned as an emergency mental health first-aid kit, embarking on a journey “of building a comprehensive digital mental health network across India and reach the unreached,” as the government noted.

The Hindu tracks its operations: the helpline has grown in infrastructure and across geography. Now, it has to solve for personnel issues, scale awareness levels, tackle data privacy concerns and reach communities living on the other side of the digital divide.

Origin story

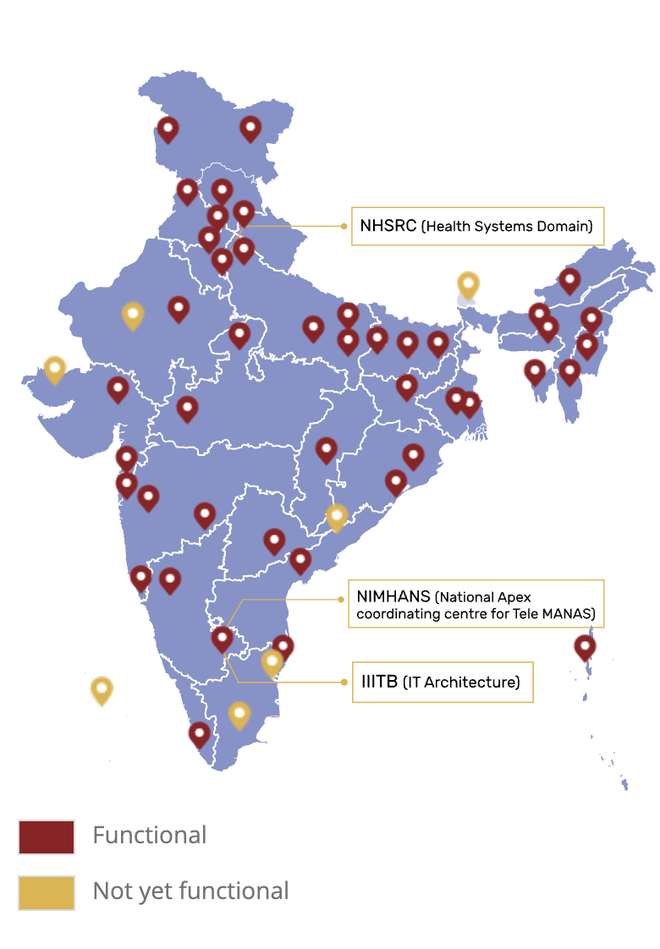

India announced Tele-MANAS, or the National Tele-Mental Health Programme, during the 2022 Budget session. It comprises two tiers: trained counsellors at State Tele-MANAS cells who provide immediate care, and mental health professionals (psychologists, clinicians, psychiatrists) at District Mental Health Programme (DMHP) who provide specialist care. NIMHANS, Bengaluru, serves as the nodal centre while the International Institute of Information Technology (IIITB) in Bengaluru is tasked with providing the technical know-how for the helpline.

Before T-MANAS, the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment in September 2020 launched a similar toll-free 24/7 helpline called KIRAN for callers to get advice, counselling and referral to psychologists and psychiatrists. The Scientific Advisor’s Office to the government is also piloting a mobile app called ‘MANAS Mitra’.

The COVID-19 lockdown witnessed a ‘mental health pandemic’ unfolding — burnout, fatigue, anxiety. 1.64 lakh people took their lives in 2021, according to the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), a jump from previous years, which experts attributed to pandemic-induced economic stress among disadvantaged communities. Even before the pandemic, the World Health Organisation noted India has one of the world’s largest populations of people with some degree of mental illness. Still, India spends less than 1% of its entire healthcare budget on mental health — translating into a shortage of professionals, specialised facilities and hospitals, especially in rural areas.

The helpline acknowledged the “mental health crisis in wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and an urgent need to establish a digital mental health network that will withstand the challenges amplified by the pandemic,” per a press release. It is conceptualised as the “digital arm of the National Mental Health Programme (NMHP)... It is supposed to act as a supplement to the existing District Mental Health Programme (DMHP)“, says Naveen Kumar C., Professor of Psychiatry at NIMHANS and Principal Investigator, Apex Coordinating Centre for Tele-MANAS. As the first line of action in the mental health loop of care, it would take services to remote populations, such that they are cost-effective and easily accepted.

The present Ministry of Health and Family Welfare budget allocated ₹134 crore to the National Tele-Mental Health Programme. The emphasis on T-MANAS and “its inclusion as a separate line item can be viewed as an indication of the government’s focus on scaling digital mental health programming,” according to an analysis by the Centre for Mental Health & Law Policy(CMHLP).

India’s state of mental health infrastructure

Scaling up

The helpline received a tepid response at the start — fielding about 25,000 calls in the first two months nationally — which was ascribed to a “hasty launch,” Dr. Rahul, an Assistant Professor at NIMHANS told a media outlet earlier this year. The State cells were understaffed and there wasn’t enough awareness generation, he explained.

The helpline crossed the 2-lakh mark in July and 3 lakh in September. Most calls are received from people in the 18-45 age group, and two-thirds of the callers are men, data shows. Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, Telangana, Madhya Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir, Uttar Pradesh, Odisha and Karnataka are the top regions in terms of callers. Andhra Pradesh’s Tele MANAS cell has prevented about 45 suicide attempts through tele-counselling between October 11, 2022, and May 9, 2023, according to the State’s Health and Family Welfare Commissioner. Jammu and Kashmir launched India’s first Tele-MANAS chatbot in July, which will be staffed round-the-clock with psychologists and counsellors.

The calls are categorised on the basis of complaints received. Data from different cells shows people under 18 years of age report exam stress, anger issues, and focus issues; those between 18 and 45 report anxiety, depression, personal and professional challenges; those above 46 speak of familial conflict, extramarital affairs, depression, and dementia, among other concerns. Sleep disorders were the most common reason cited, followed by sadness and stress. Women, who accounted for 70% of callers in Jammu and Kashmir, dialled in “either with underlying mental health problems or distress arising from immediate stressful causes like domestic violence, death in family, illnesses in family,” Dr. Heena Hajini, senior consultant at Tele-MANAS, told a media outlet.

Training and recruitment for Tele-MANAS

Approximately 2,000 counsellors are spread throughout the country, providing support in consultation with mental health professionals. People needing targeted, prolonged care and support are referred to appropriate healthcare facilities and specialists including psychologists, psychiatrists, social workers and nurses; they may also be linked with “e-Sanjeevani, Ayushman Bharat health and wellness centres and emergency psychiatric facilities”, a press release noted.

The counsellors are still the first line of contact, and are trained based on a curriculum (NIMHANS plans to apply for accreditation) prepared with inputs from professionals, policymakers, NGOs and users of mental health services/carers. Online and offline training sessions further discuss how “care can be provided in a more effective way - what to do as a counsellor, what not to do, where to draw the line,” Dr. Naveen says.

If someone calls with exam anxiety, for instance, the counsellor will support the person until the exam is over or the immediate crisis is resolved to “complete the loop of care.”

“There is a procedure to schedule callbacks until the crisis is handled or the person says they don’t need further help... the counsellor makes a judgment call in consultation with mental health professionals.” Callbacks are scheduled only after the caller’s consent. A software also records the case history so “that if the same person calls again, there is continuity in care. This also helps in recording data for formulation of policies in future,” T.K. Srikanth, Principal Investigator from IIITB, told reporters earlier.

Advice and intervention vary based on the caller and the urgency of the issue. Yoga, meditation, and breathing exercises are often advised for exam stress and sleep disorders. Quality assurance of mental health advice becomes challenging for other, more complex issues, such as a woman calling to seek help for domestic violence, where counsellors may not be adequately sensitised or informed. Dr. Naveen says psychologists, psychiatrists, nurses and social workers are there to offer specialised support when such a need arises. Over time training has expanded into holding discussions on gender inequality, domestic violence, and misuse of the POCSO Act to criminalise romantic relationships. When asked about if systemic inequities such as caste and religious discrimination are discussed, Dr. Kumar said “we are in touch with counsellors across the country and we take up issues as and when they come up”.

Counsellors are also batting an unpredicted challenge: prank calls. Approximately 90% of calls are routine (exam, anxiety related), 6.22% are emergency-linked and about 4% of calls so far have been bogus — some making offensive and sexual remarks.

The resources are under-utilised, says Dr. Naveen, noting that the helpline is operating at 15% of its full potential in terms of call loads due to a lack of awareness. Moreover, counsellors are not permanent employees but a “floating group,” complicating a sluggish recruitment process where even advertisements don’t yield an enthusiastic response. In Andhra Pradesh, for instance, there are 13 counsellors in the cell— against 20 sanctioned posts.

Lingering concerns

Consultations are increasing, but Tele-MANAS does not have a data privacy policy, NIMHANS revealed in an RTI response to the Centre for Health Equity, Law and Policy (C-HELP). Patient data is stored in cloud services of companies approved by the Centre’s Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology. Data privacy laws apply to all information about a person (including mental health), the Supreme Court affirmed in 2017; the data should thus be protected under India’s Information Technology Act, 2000 and the contentious Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023. At present, it is unclear what data is recorded, how it is used and who has access to it. This year, vaccine portal CoWIN’s data was breached, with a Telegram bot spewing out personal details like name, Aadhaar and passport numbers of people.

Dr. Naveen says NIMHANS is working on incorporating data protection rules per the provisions of the new Act, but “cannot disclose” how this will be implemented. At present, no calls are recorded and he notes that principles of confidentiality and consent are “fundamental and will be kept in mind.” As digital mental receives a government push, “the absence of regulation poses a considerable risk to the protection of mental health data and rights of persons with mental illness”, researchers from the Centre for Health and Mental Health and CMHLP argued. The right to privacy and confidentiality are incentives for people to access tele-mental health services in a landscape muffled by mental health stigma, they note.

In February last year, Health Minister Mansukh Mandaviya said the free helpline would “play a crucial role in bridging a major gap in access to mental healthcare in the country.” Currently, there is no detailed, disaggregated record of the socio-economic profile of callers — their gender, caste or class status, making it hard to assess the reach and engagement of these services among the “unreached”. Dr. Naveen says the helpline will incorporate metrics in the interactive voice response system (IVRS) over the next few months to map region-specific demand.

Previous research has identified that those with mental health issues and most in need of help often experience poor digital literacy and lack access to smartphones and internet connections. A mobile-based mental health project centred on depression and anxiety was piloted across 42 villages dominated by Scheduled Tribe communities in Andhra Pradesh. While it helped with diagnosis, poor internet connectivity and limited infrastructure plagued its impact.

Phones, internet and privacy — the planks for a tele-mental health service — are also harder to come by for women. Less than a third of Indian women own a mobile phone; about 33% fewer women than men have access to the internet to know about government-run helplines.

“We are yet to realise the full potential...Calls are rising but still, vast swathes are untouched as awareness hasn’t reached the grassroots. ” Naveen Kumar C., Professor of Psychiatry at NIMHANS and Principal Investigator, NIMHANS

Experts also warn against favouring one solution over tackling other systemic barriers. The budgetary estimate for the Tertiary Care Programme (which is responsible for State-run mental health hospitals and mental health specialist training) dropped by 42% this year. Public health scholars have cautioned that telepsychiatry may trade quality care for “market efficiency, productivity and cutting costs, redistributing existing psychiatric resources rather than creating and investing in community mental health, rehabilitation, recovery and caregiving.” Dr. Naveen admits that the helpline is itself “a small spoke in the larger circle of care.”

Moreover, the helpline’s functioning requires a simultaneous investment across all sectors of mental health. Tele-MANAS counsellors refer and physically take people to specialised personnel, medical colleges or hospitals with equipped facilities if needed, but doing so requires real-time knowledge of mental health resources, say, where psychologists are available or the number of functional clinics. Resource mapping is a “gigantic exercise” and will it at least one to two years to collect all resources, says Dr. Kumar, but “is very important in the Tele-MANAS scheme of things.”

The next year is crucial not only for raising awareness and reaching out to people, but also overcoming recruitment challenges currently hindering the helpline. When demand is created by the users, naturally, all the barriers tend to get broken, he adds.

“We want to take this message to every nook and corner of the country... to tell people, look this number is available... Help is just a phone call away.”