New Zealand workers are still being maimed and killed in huge numbers, but WorkSafe’s boss is ambitious to deliver change. Rebecca Macfie reports.

Phil Parkes was trained as a regulator in the ways of “the carrot, the stick and the sermon” - incentives, punishment and guidance. But two years into his role as chief executive of WorkSafe, he speaks of “root causes” and “culture”, “upstream duties” and “organisations with influence and control”.

Carrots, sticks and sermons are still essential tools, but they are insufficient to bring about the profound changes necessary to keep workers safe. He argues a modern “insights-driven” regulator needs to understand the business models, supply chains, terms and conditions, and contracting arrangements that determine whether work is good or bad for the people who do it every day.

Death, life-changing injury and illness at work are symptoms of “work done badly”, he says. Fixing New Zealand’s appalling record of health and safety is, therefore, about the quest for “better work”.

“Work is not just delivered by frontline workers and supervisors,” Parkes told Newsroom in an interview last week. “It’s delivered by people who set up organisations, leaders who set the culture, directors who make the financial decisions, the architects who design the buildings, the owners of forests who decide where to plant the trees ... There is a huge [number] of players in the work economy that have health and safety responsibilities, and influence and control, that don’t always sit in the business that carries out the frontline activity”.

These players are within WorkSafe’s reach, he says - whether through hard enforcement, persuasion and education, or public shaming. The directors of a corporation whose subsidiaries repeatedly harm workers can expect the regulator’s close scrutiny; so too can the supplier of dangerous equipment.

Parkes is even trying to get WorkSafe to the point where it can “shine a light” on - for example - foreign pension funds with shareholdings in forest companies in whose service logging workers are killed. That might mean a letter or a video call from him to point out that the toll on workers doesn’t square with said shareholder’s claims of ethical and sustainable investment, or perhaps some uncomfortable media exposure.

Parkes’ aspirations are a far cry from the banal reality of hard hats and toolbox talks, compliance forms and SMEs who fear the WorkSafe bogeyman will come after them for some minor transgression.

“It is progressive,” he says of the direction in which he is trying to take the agency. “And it’s hard.”

For those who see WorkSafe’s job as simply prosecuting the direct employers of workers who are maimed or killed, it can also look like radical over-reach. But Parkes is channelling the research and advice that led to the establishment of WorkSafe in 2013 and the introduction of the Health and Safety at Work Act in 2015.

Both reforms were born out of the Pike River mine catastrophe, when there was universal recognition that New Zealand needed to get to the tap root of our blood-soaked workplaces. Pike, with its devastating combination of inept board, disinterested owners, feeble regulator, silenced employees and legion of small contractors, was a shattering case study the nation was obliged to learn from.

The father of WorkSafe, then-Minister of Labour Simon Bridges, described the new stand-alone regulator as the vehicle for “transformation”. He said the reform package would create a “world-class” health and safety system that would be a legacy to the 29 men and boys entombed at Pike and the 75 workers who died every year in traumatic incidents. He called it a “once in a life time opportunity to take a systems-wide approach”.

The new regulator would be properly resourced, and employ more and better inspectors than the failed Department of Labour occupational health and safety unit. There would be a full suite of underpinning regulations - promised but never delivered under the 1992 Health and Safety in Employment Act - to enable it to do its job.

A key part of the post-Pike reforms was the concept of “upstream duties” - the idea that responsibility for keeping workers safe extended far beyond the direct employer. As the 2012 Independent Taskforce on Workplace Health and Safety put it, the typical response to death and injury had been to “seek and blame an immediate cause or responsible person”. Instead, the new regulator needed to “examine the root causes of incidents”.

Parkes’ vision for a health and safety regime that takes account of the wider economic forces that shape the risks faced by workers therefore shouldn’t come as a surprise. And yet it does.

Untransformed

WorkSafe is into its ninth year of life. Parkes is its third chief executive, having risen from the ranks of senior management. The Health and Safety at Work Act has been in place for six years. But the promised transformation is not yet in sight.

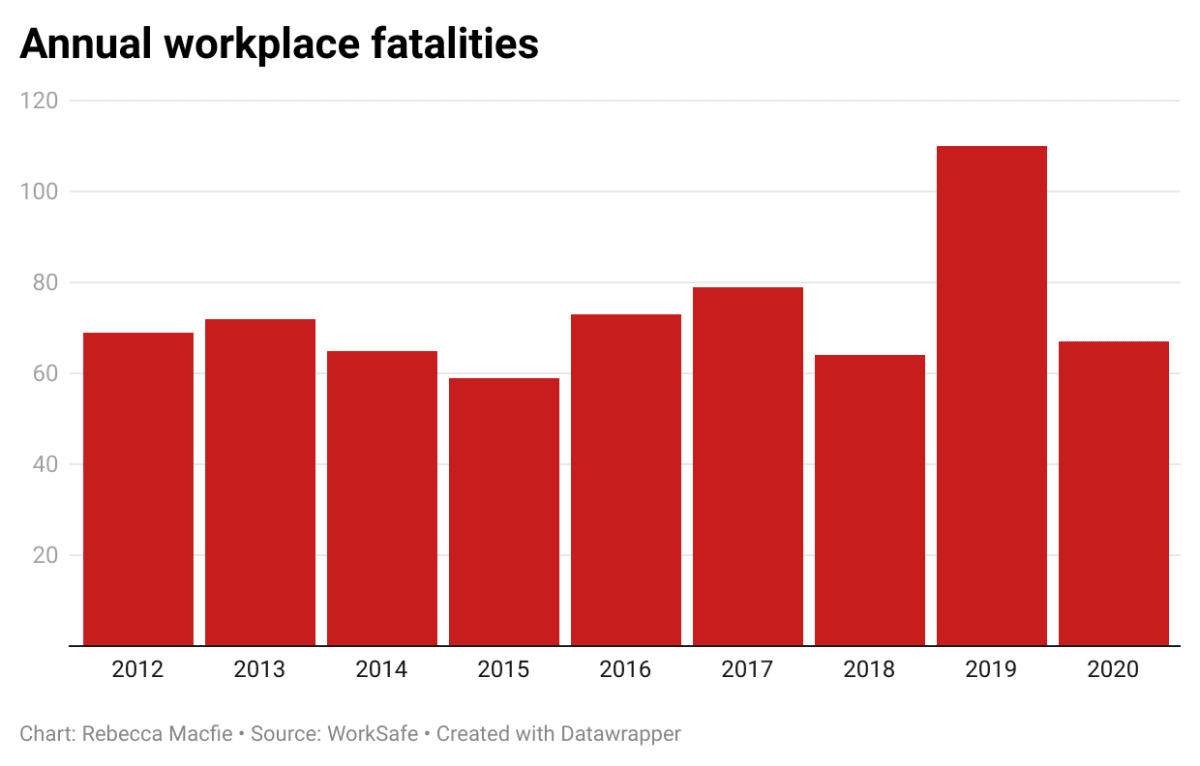

We still kill about as many workers on the job as we did back then. Toxic work slowly kills another 750–900 every year from diseases such as cancer and respiratory illness. Some 5000–6000 people wind up in hospital each year from grinding work-related ill health. Every year more than 30,000 have to take a week or more off work because of on-the-job injuries - and the burden of this falls disproportionately on Māori workers, whose casualty rate is 55 percent higher than non-Māori.

Highly skilled workers still labour on sites with such wafer-thin defences that a single mistake can cost their lives, with their grieving families then advised that their loved one was to blame for their own death.

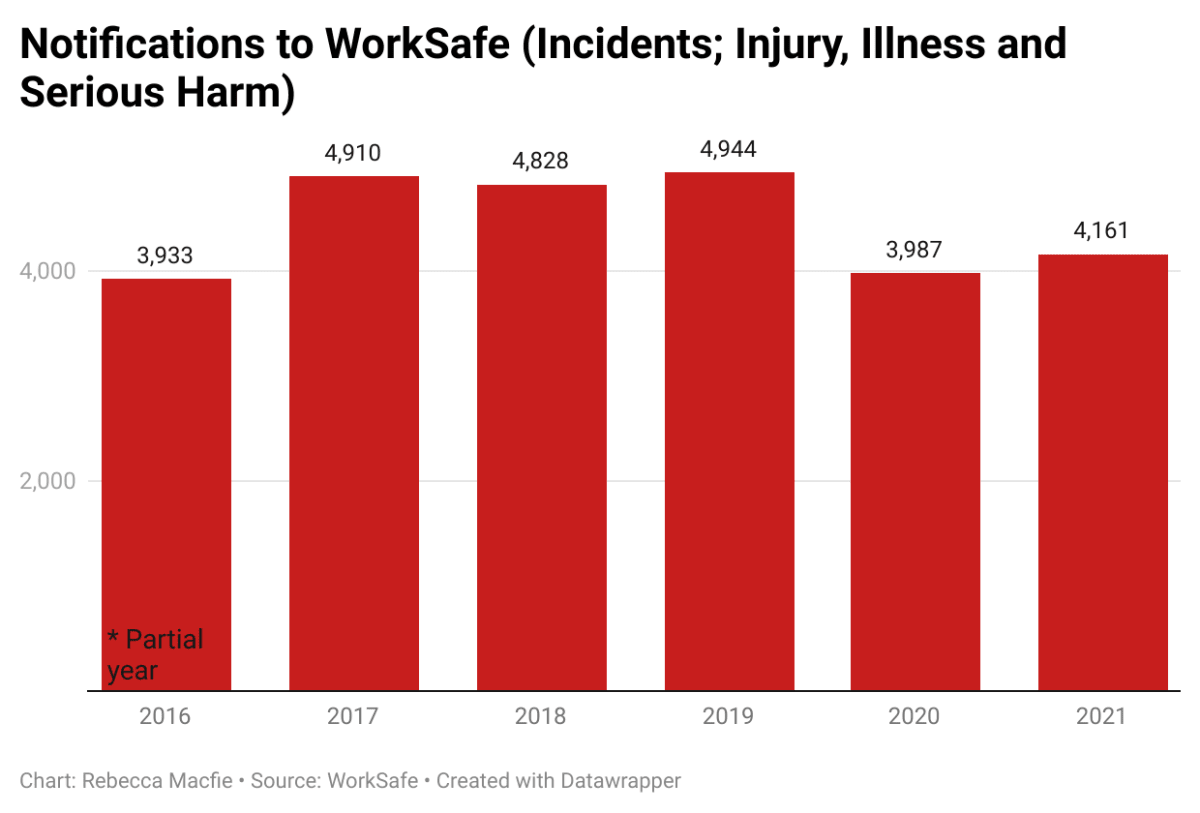

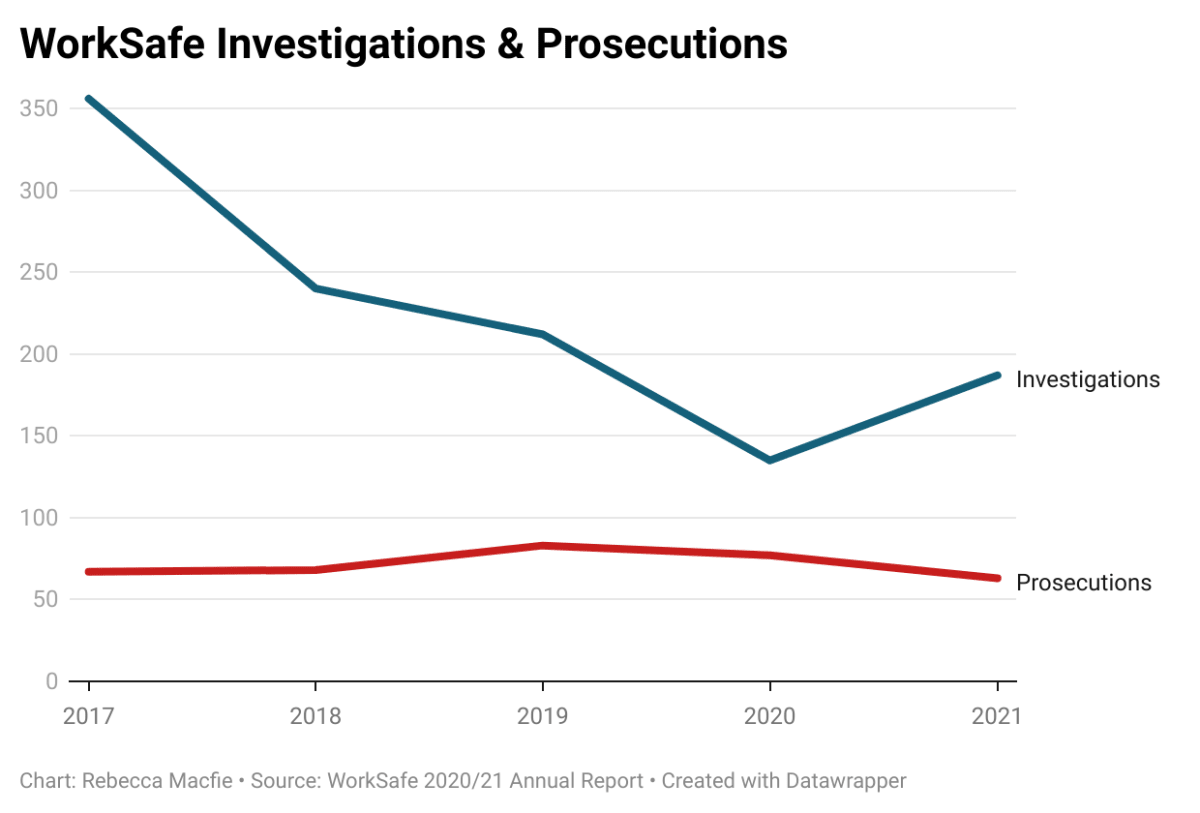

The vast majority of accidents and near-misses go unpunished. Of the nearly 27,000 notifications to WorkSafe over the past six years, only 4 percent have led to an investigation, and only a third of those investigations have led to prosecution.

The agency has been hammered for a declining number of investigations in recent years. In reply, Parkes says this is because it is targeting resources more tightly towards cases likely to lead to prosecution, and that the proportion of investigations leading to court charges has been increasing. There has also been the huge Whakaari/White Island investigation, which soaked up 40 percent of WorkSafe inspectors, and the extra duties and constraints imposed by Covid19.

None of which does much to ameliorate the hurt felt by families left angry and re-traumatised by the lack of accountability.

The WorkSafe inspectorate has still not reached the numbers that were promised when the agency was created in 2013. MBIE, the health and safety policy agency, is years late in developing the promised suite of regulations, causing undisguised frustration to WorkSafe.

Bridges has gone from staunch health and safety reformer to quibbler-in-chief about compliance costs. And while there are progressive company boards committed to a holistic approach to worker safety, there are many other directors who, having swept their assets into trusts to protect themselves from the stiff penalties of the new Act, are fixated with trivia or have gone back to being bored by health and safety.

After all the post-Pike reform and ambition, we seem to be stuck back where we were in 2010 when the mine blew up.

Paddling upstream

So is Parkes getting ahead of himself with his ideas of “better work” and “upstream duties”? Given the awful statistics, shouldn’t he get back to his sticks and carrots, and focus on prosecuting far more of those whose shabby workplaces kill and damage workers? Never mind putting the acid on the far-flung forestry investor whose only crime is to receive the dividends from the booming log trade; get stuck into the logging contractor whose utes and haulers and men are out on the job 12 hours a day.

Newsroom understands that MBIE, which is also WorkSafe’s monitoring agency, thinks Parkes is taking WorkSafe beyond its mandate and ought to stick to his knitting. But he is pushing on regardless - within the constraints of his budget and a pile of additional enforcement work imposed by Covid19 - and trying to take business, union and Government leaders with him.

“WorkSafe is very clear that to be effective we need to change our regulatory model. That means that we need to be progressive and disruptive and - your word - radical,” he tells Newsroom. “The challenge is that for some people across various agencies, and that does include sometimes the policy agency, the traditional view of health and safety is that it exists in a swim lane, that it is mainly about doing inspections and taking enforcement. And we are very clear that whilst that will always be core business and we will never not do that role, we need to have different approaches, and that requires an understanding of where health and safety fits into business models, which is why we’re going upstream.”

Hence WorkSafe has brought in forestry veteran Warwick Foran to provide a detailed economic analysis of that sector. In the first phase of his work, Foran has mapped out the forest owners, managers, exporters and land-holders, the structure of harvesting contracts, production pressures on logging crews, and how all this can contribute to stress, fatigue and congestion out on the remote sites where so many forestry workers end up dead.

By understanding how the whole system works, WorkSafe can better decide where to intervene, says Parkes. “And the approach will be different depending on who we are talking to, and what their reaction is.”

The decision last year to prosecute Ernslaw One - part of the Oregon Group, owned by the Malaysia-based Tiong family - is a sign of WorkSafe’s growing confidence to chase responsibility upstream to asset owners. Four logging crew workers were killed harvesting Ernslaw’s trees between 2017 and 2020, so WorkSafe’s decision to prosecute the company (alongside the direct employer, Pakiri Logging) over the death of a Tairāwhiti worker in 2019 barely scratches the surface. However the $288,000 fine imposed on Ernslaw sent a pointed message to other forest owners that they can’t wash their hands of responsibility for the dangerous business of harvesting their crop.

The Talley’s tally

Similarly, Parkes’ decision to deal with the recidivist Talley’s Group as a single project, rather than playing endless whack-a-mole with its subsidiaries, is a sign of the new strategy.

The final trigger for the move on Talley’s was reporting by TVNZ’s Thomas Mead, which fell on fertile ground at WorkSafe. Between the start of 2018 and July last year, when Parkes announced a major review of the sprawling Motueka-based food company, Talley’s-owned businesses had been prosecuted by WorkSafe five times, with a sixth - over the death of a meat worker at its Affco plant at Wairoa - still to be heard.

Over that same period the company had also been slapped with 43 enforcement notices under the Health and Safety at Work Act, including prohibition and improvement notices.

Details released under the OIA show that at Talley’s Affco plants alone there have been 86 notifiable events of injury, illness and near-misses between the start of 2017 and September 2021. These include a dozen ammonia leaks, five cases of the debilitating disease leptospirosis, and multiple lacerations, crush injuries and burns.

Parkes has met with the Talley’s board, and inspectors have issued 28 enforcement notices in the seven months since the review started, including at Talley’s Open Country Dairy subsidiary. The board has agreed to submit itself to a Safe Plus review - a voluntary self-assessment tool for companies which focuses on leadership, worker engagement and risk management.

There’s no guarantee that any of this will lead to safer work at Talley’s plants. Parkes’ team may conclude the only way to influence the company is to hit the directors and senior officers with litigation. Or they could make a long-term commitment to change, perhaps using the voluntary enforceable undertaking provision allowed for in the 2015 legislation. Although these have been used by companies to avoid hefty fines, supporters of the approach believe they can be a platform for lasting improvements for workers.

Success with Talley’s would be a significant feather in Parkes’ cap, and a boost to WorkSafe’s mana.

Next year will bring a much greater test of the agency’s credibility, however, when its lawyers stand in court to prosecute the owners of Whakaari/White Island, GNS, the National Emergency Management Agency, and tour operators whose clients perished when the volcano erupted in 2019.

Parkes and WorkSafe’s regulation and legal manager, Mike Hargreaves, say the Whakaari charges are examples of sheeting responsibility beyond the immediate tour operators, and that the resulting court decisions will help clarify just how far upstream the boundaries of the law lie. But the case is also likely to be a brutal test of WorkSafe’s own credibility, given its failure to adequately monitor the tour operators on the island.

Parkes is articulate, confident and ambitious for change, and he has support from significant quarters. Council of Trade Unions’ president Richard Wagstaff is frustrated by the low number of prosecutions and WorkSafe’s inadequate resources, but he applauds Parkes’ focus on the systems and culture of work that push risk onto employees. Business New Zealand’s CEO Kirk Hope is onboard with the idea of a “cultural shift”, although it’s less clear that he comprehends Parkes’ desire to reach up the supply chain to the principals, asset owners and others who influence the structure of work.

The difficulty for WorkSafe is that more ambition means squeezing more productivity out of the same set of resources. There are only 180 inspectors for the whole country, and it’s much easier to find a smoking gun by investigating a small-time rural forestry contractor than spending months hunting for clues in the board minutes of deep-pocketed owners. It’s much easier to mount a prosecution over a sudden traumatic fatality than a slow, debilitating death from work-related lung disease.

George Adams, who chairs the Business Leaders Health and Safety Forum and in 2014 served on the independent inquiry into the forestry industry’s shameful record, agrees that improving health and safety relies on improving the quality of work. But he cautions that it’s a “wickedly complex problem, and it needs to be managed from multiple angles”.

“The lens we used in the past was relatively narrow … All we were really interested in was that if you came to work with four limbs and 10 digits, then you went home with them intact.

“But we really have to think about health and safety as being about productivity, about retention, employment brand, and thriving workers. And the conditions that enable people to thrive at work don’t come about by accident.”