A woman has sued the city of San Francisco after her DNA from a rape kit following a sexual assault was used to arrest her in a separate property crime case.

The unidentified woman, referred to as Jane Doe, filed a federal lawsuit on Monday, arguing that the San Francisco Police Department had committed an “unconstitutional invasion of privacy”.

The DNA of the woman was handed over to police in 2016 during an investigation into her sexual assault, according to the lawsuit.

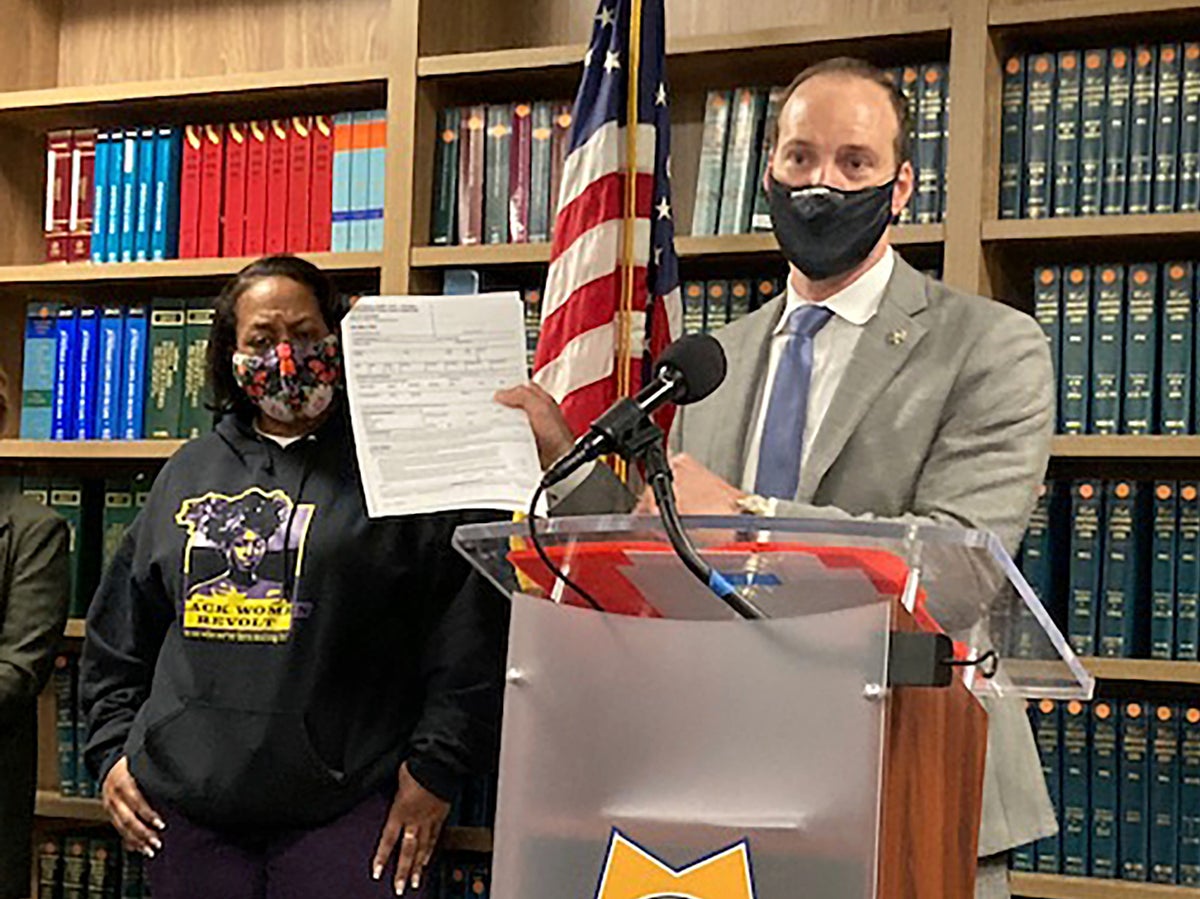

Her attorney Adante Pointer told The New York Times on Monday that the police used that DNA around five years later in order to charge her with retail theft.

The lawyer said that her DNA was put into a database without her consent or her being made aware of the measure. Using the DNA database to identify potential suspects was something the police also did to other survivors of sexual assault, according to The Times.

“The exchange is you’re going to use this DNA for a specific purpose, which is to prosecute the person who violated me,” Mr Pointer told the publication. “And instead, the police turned into the violators here.”

Earlier this year, the Board of Supervisors greenlit an ordinance that prevents the police from identifying suspects using DNA taken from rape kits.

The use of the DNA database became known during the investigation into the woman’s case earlier this year. The city district attorney at the time, Chesa Boudin, chose not to prosecute the woman.

Sexual assault survivors had been used “like evidence, not human beings,” he told the press during a news conference in February.

The lawsuit seeks unspecified damages.

A San Francisco city attorney spokesperson said in a statement that the city “is committed to ensuring all victims of crime feel comfortable reporting issues to law enforcement and has taken steps to safeguard victim information”.

“Once we are served, we will review the complaint and respond appropriately,” the spokesperson added.

The San Francisco Police Department told The Times that the agency doesn’t comment on pending lawsuits.

The police department’s crime laboratory has since responded to outrage from victims’ advocates, saying that they would no longer use DNA from rape victims in investigations of separate crimes, the San Francisco Chronicle reported.

Mr Pointer told The Times that his client, a Black woman, felt that the ordeal cemented her feeling that women of colour “are often targeted by the criminal justice system”.

“Their civil rights are trampled upon, repeatedly and continuously,” he said. “So that’s another part of this – making sure that we stand up for people in this society who oftentimes don’t have their rights respected.”

Mr Pointer said the case against the man accused of assaulting the woman was dismissed.

California lawmakers voted through a bill in August that would prevent law enforcement from using sexual assault victims’ DNA for anything else but finding their attackers.

Wright State University professor Dan Krane in Dayton, Ohio has investigated the tools used to assess DNA for use in criminal cases. He told The New York Times on Monday that federal law forbids rape victims’ DNA from being put into the national Combined DNA Index System.

But he added that local versions of that law are scarce, meaning there are fewer restrictions on how local databases can be used.

He said most law enforcement departments act like “stamp collectors” when gathering DNA.

“The more people they can get in the database the happier they are,” he said. “You’d think this is some type of sci-fi movie. But it’s real life.”