Caste is a living reality in India. A person may change his religion but caste follows him. It’s worse for those whose traditional occupation defines them to this day. Debut author Radhika Iyengar gives an in-depth picture of the life of one such community, the Doms of Banaras, without whom moksha is not considered possible by some Hindus. But how do they go about life in the city of death? How challenging is life around the cremation grounds? Through her richly detailed book, Fire on the Ganges, she paints a picture of the community. Edited excerpts from an interview.

For a first-time author, you have chosen a subject most would shy away from. What led you to this book? How long was the research?

In public consciousness, the Doms’ lives have been solely associated with their labour of cremating corpses at the ghats. When I began reporting, there were no informed, accessible, alternative narratives surrounding their lives. The questions came from trying to understand what motivated this community beyond the cremation ground? What choices were the men making each day? Did the women work outside their homes as well? Did the children go to school, and if they did, was it good quality education? Surely, the younger generation nurtured professional interests different from working at the cremation ground? Were there those who managed to break away from an inherited deeply caste-bound profession? These questions could only be explored against the larger backdrop of the Doms’ crematory work. From the time I began the research and writing, it has taken 7-8 years.

Early in the book you talk of a Dom boy who had been to Manikarnika Ghat daily from an early age. How difficult is life among the dead?

For the Dom children who scavenge shrouds at Manikarnika Ghat, it is a tough existence. Who would want to grow up watching hundreds of corpses being set ablaze? Witnessing such sights each day can, and does, have a deep, scarring impact. The children have no option but to internalise such experiences. Over time, it becomes their ‘normal’. Their work involves operating near the burning pyres. They often hurt or burn themselves on the job. They get bullied and smacked around by other labourers at the ghat. It is an extremely hostile working environment.

Will it be fair to say, ‘Fire on the Ganges’ is a comment on social oppression in the name of religion?

The book is many things. For one, it tries to draw focus on a few individuals from the Dom community who are challenging society in their own ways to lead lives on their own terms, whether it is through education, running a small business or other alternative means. At the same time, it tries to examine how a community that performs a specialised funerary practice continues to be regarded as ‘untouchable’ by a majority of caste Hindus. In Banaras, it is believed that if a Hindu is cremated by a Dom, they will receive moksha. In this context, the Doms carry religious capital but it only exists till the boundaries of the cremation ground. In reality, no privileged, dominant caste individual will be willing to perform such back-breaking, caste-ridden labour.

Banaras is famous for death. Yet in many ways, it’s the dead who keep the living going. How does one explain the anomaly?

Banaras is a city of many things. It’s a city of winding alleyways, of legendary ghats that have stood the test of time, and a city of worship. It’s a city where aartis are held on a grand scale. It is also a city of ‘moksha’ — liberation from the cycle of death and rebirth. However, while we speak about moksha, we hardly think about the community that delivers it. For centuries, the Doms have been performing the task of cremation. This is their primary source of livelihood, one that provides a meagre income. So, they try to use everything available at Manikarnika Ghat to earn more — from sifting the ashes to find remnants of gold and silver, to scavenging for and reselling the red and orange hued shrouds that drape the corpses. As I write in my book, ‘At Manikarnika Ghat, nothing goes to waste. Almost everything is reclaimed from the dead to make a living’.

You talk of ultimate humiliation in lower caste people being given undigested corn from cattle excreta as wages. Can you elaborate on this inhuman practice?

In one of his writings, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar describes how in parts of Uttar Pradesh, bullocks would tread over harvested corn on the threshing floor and sometimes consume some of it. ‘Gobaraha’, which was undigested corn found in cattle dung, would later be separated and given to the Dalit workers as wages. According to Dr. Ambedkar, the labourers would grind the corn and use the flour to make bread. This provides a stark picture of how the practice of giving unpalatable or leftover food to oppressed castes in lieu of monetary compensation is linked to decades of humiliation and pain.

Humiliating as caste oppression is, isn’t subjugation of women a greater social concern? You talk of women denied education and jobs, etc.

I don’t think we can compare which form of oppression is a greater social concern. All forms of oppression are incapacitating. In many parts of our country, girls continue to be denied their basic right to education or are pulled out of school before they reach puberty. In Chand Ghat too, by the time a girl turns 14, she is forced to drop out of school and her movements are curtailed. Conversations around marriage begin. I have met girls in the Dom neighbourhood who are extremely alert and intelligent. They can do wonders if they are given the right education and opportunities. So, one hopes that mindsets will change.

Finally, what was the situation during the pandemic at Manikarnika, Harishchandra and other ghats?

At the cremation grounds in Banaras, when the pandemic was at its peak, there was a point when firewood depleted. Bodies continued to pile up. Some of the corpse burners, understandably so, feared for their lives and did not want to work. Cremators who continued to work at the ‘masaan’ (cremation ground) did so while risking their lives, without any protective paraphernalia. During this time, the cost of everything rose exponentially. The fee for crematory services increased as well. The corpse burners who laboured during this intense period managed to make three or four times their usual income.

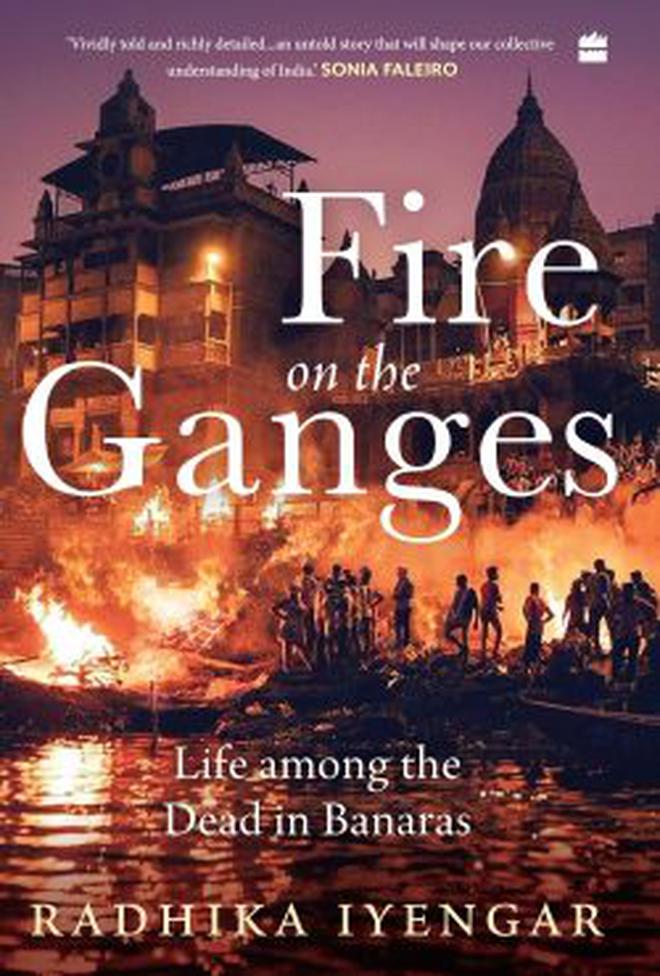

Fire on the Ganges: Life Among the Dead in Banaras; Radhika Iyengar, HarperCollins, ₹599.

ziya.salam@thehindu.co.in