If you are a student and spend much of your time on the internet, the chances are you have come across an account or website that offers to do your assignments for a fee.

Some of these services are fully-fledged businesses. Some are one-person operations. Whichever it is, “contract cheating” – a term coined in a 2006 study by English scholars Thomas Lancaster and Robert Clarke – is a process by which students hire a third-party to complete work on their behalf.

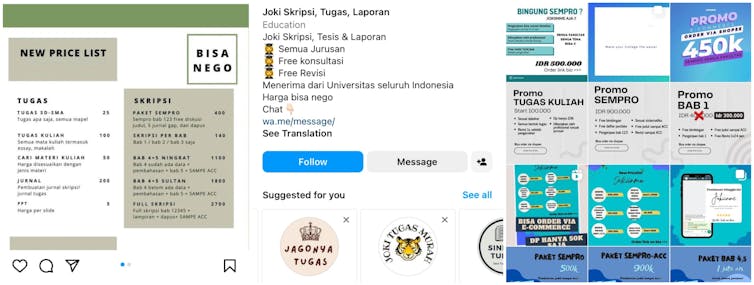

Known in Indonesia as “joki”, these operations provide expertise in research, writing, or even technical undertakings such as creating software, and perform per students’ requests. They can rake in hundreds of thousands to millions of rupiah (tens to hundreds of US dollars) from a single transaction.

Data regarding contract cheating providers in Indonesia and how frequently students rely on them is scarce. But to give some global context, a 2018 study from Swansea University in the UK revealed that around 15% of university students around the world have hired someone to complete at least one of their assignments.

In Indonesia, there has been a spike in instances of academic dishonesty by students, resulting in a rapid rise of research and literature on the importance of maintaining integrity in the academic setting.

This is especially evident in the higher education environment where students are prepared to enter the workforce and expected to do so with a mature sense of personal responsibility.

In fact, some of the most lucrative opportunities for service providers not only include entrance exams for public universities and assignments while studying, but also government job recruitment processes once students graduate. Competition for these institutions are so tight that some Indonesians opt for third-party help. Only a couple of weeks into this year, reports surfaced of joki intervention during a state-owned enterprise (SOE) recruitment test.

Why contract cheating is widespread

The contract cheating industry exists to cater to the needs of students.

Many of them take advantage of students who are disillusioned by their prospects of receiving top marks in certain classes. This can be fuelled by expectations of peers or family members. Other providers may take on clients who have lost motivation to satisfy academic standards, or are currently grappling with responsibilities outside of school such as part-time jobs that consume most of their attention and time.

There is also a psychological aspect at play. Contract cheating providers frequently advertise themselves under the guise of “support services” or by using marketing that dangles the possibility of maximising leisure time despite having academic work looming.

They effectively manipulate students into believing that cheating is normal. The sustained expansion of the contract cheating clientele creates the impression among students that they are merely partaking in an academic rite rather than being dishonest.

As with any other type of business, the commercial success of contract cheating providers depends on their ability to reliably supply a wide range of services and meet the specific needs of those seeking assistance.

Providers can easily be found across online platforms and marketplaces.

On social media, providers do not hesitate to tag official school and student organisation accounts. In addition, the use of contract cheating has grown rapidly since the COVID-19 pandemic. As school activities and government recruitment exams for graduates increasingly move into the virtual space, service providers have more freedom to reinforce their presence and operate undetected.

No clear rules

But supply and demand are not the only things that grease the wheels of contract cheating. Regulation of these services under Indonesian laws are obscure at best.

It is equally unclear if either providers or their clients could be penalised.

Indonesian legal observers argue that students who turn in an assignment done by another person under their own names could be committing a form of copyright infringement. However, this may not mean much as contract cheating is transactional and providers are unlikely to assert intellectual property rights over the use of paid-for work.

Others argue that cheaters could be prosecuted for fraud or forgery under the Indonesian Penal Code for misrepresenting someone else’s work as theirs in pursuit of personal advantage.

While logically sound, this reasoning begs the question of whether criminal prosecution is indeed the appropriate solution when we remain undecided on the precise definition of contract cheating and whether penalties could extend to both providers and students.

Contract cheating is also so ubiquitous today, and operates in scales large and small, that it’s hard to imagine law enforcement using up resources to chase after every one of them.

It is no surprise, for instance, that contract cheating persists in some Commonwealth countries that have legislated against it. Australia passed such legislation in 2020, yet by 2022 it had only seen one court injunction filed against an overseas essay factory.

The Indonesian academic ethics framework has not yet recognised contract cheating. The term closest in definition used in some ministerial regulations is plagiarism – which is defined as appropriating as one’s own the work of others.

Baca juga: When does getting help on an assignment turn into cheating?

But plagiarism and contract cheating are conceptually distinct; plagiarism does not pivot around a willing exchange of service and payment between parties.

It could well be part of contract cheating, where an amateurish provider recycles his or her own work for multiple clients, in which case students risk getting sniffed out and being academically sanctioned. However, providers increasingly avoid this, and that means they are harder to detect.

Though specific regulation prohibiting the act of contract cheating might help, however, it won’t entirely eliminate the problem. While the law may prevent businesses from advertising illegal and unethical services, it does not necessarily alter students’ mindsets from attempting to commit academic dishonesty.

What universities can do

Despite the myriad of difficulties in eradicating contract cheating, there are ways to minimise its presence.

Academic misconduct must be clearly regulated at the university level, coupled with reliable on-campus student counselling so students can communicate any academic-related concerns rather than seeking external help. Institutions may also opt for establishing a whistle-blowing system to identify cheats.

Finally, it is crucial that Indonesian academia diversifies the metrics by which students’ performance is judged and explores personalised methods which could evaluate their understanding of the subject at hand – such as oral presentations – and train practical skills necessary to help them navigate post-university life.

Para penulis tidak bekerja, menjadi konsultan, memiliki saham atau menerima dana dari perusahaan atau organisasi mana pun yang akan mengambil untung dari artikel ini, dan telah mengungkapkan bahwa ia tidak memiliki afiliasi di luar afiliasi akademis yang telah disebut di atas.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.