Our political ability to confront climate change will be greatly diminished if the Greens don't get their act together and realise that both activists and experts must play a role

Comment: Aotearoa, with the rest of the world, urgently needs to take transformative action on climate.

But it won’t happen, here or anywhere else in the world, unless people achieve a deep, broad and enduring commitment to climate action in their political systems.

No way that’ll happen, though, under politics-as-usual. All parties, here and around the world, are too tribal. Pitting people against each other is their default setting.

However, bringing local communities together on issues, particularly on highly complex, interdependent ones – climate above all – is by far the best way to change such dysfunctional behaviour.

Remarkably positive, even confounding, things happen. Such as the Green Tea Coalition on solar power in the US between some members of the Tea Party and the Sierra Club, the historic flagship of the conservation movement.

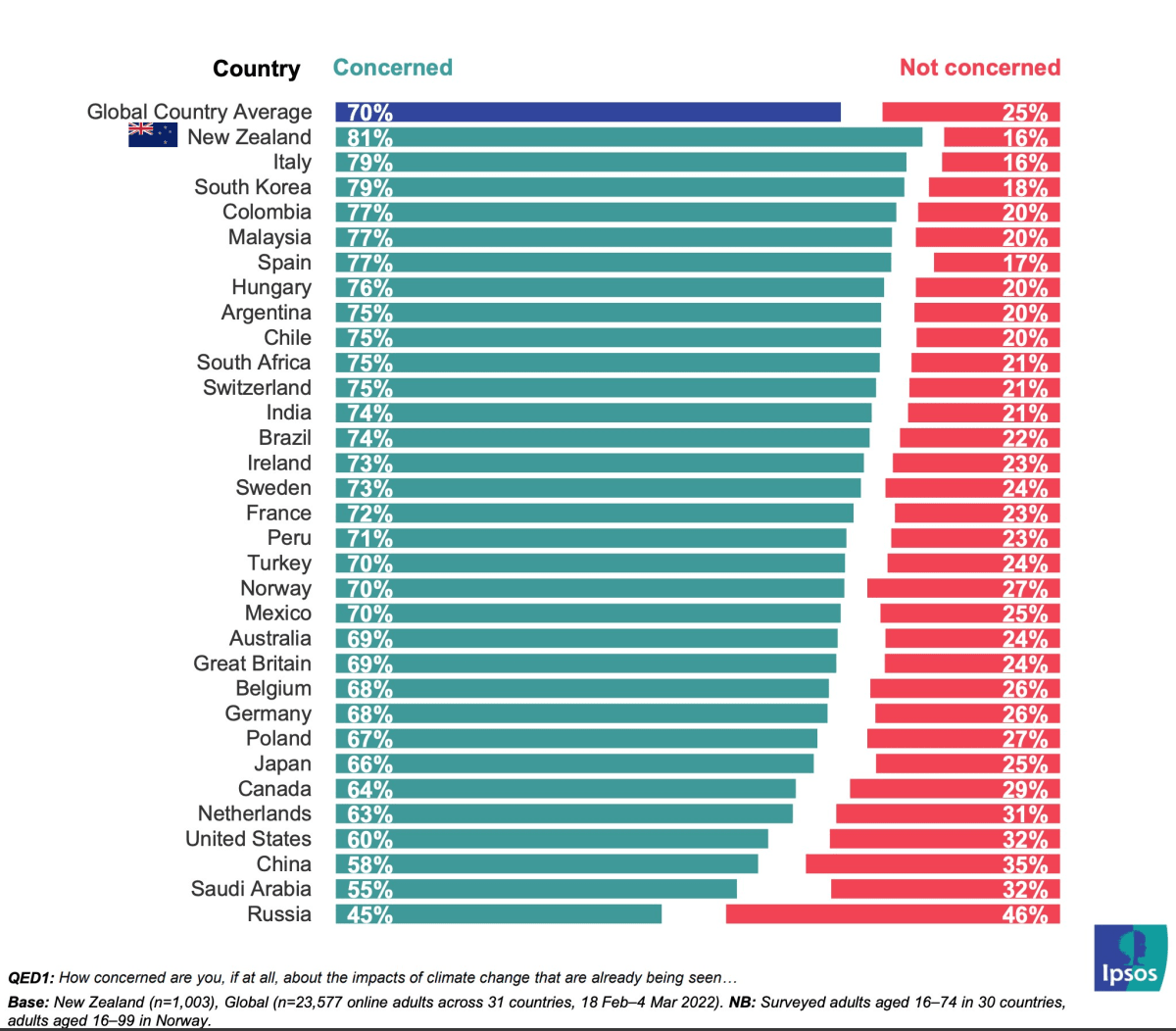

We Kiwis have lots of common ground on which to build understanding and co-operation on climate. Above all we worry the most about it among 32 nations surveyed in Ipsos’ latest annual global report.

Here are three measures of the passion and urgency Kiwi respondents expressed in the survey:

- 65 percent said if the government does not act now to combat climate change, it will be failing the people of New Zealand (up from 57 percent last year)

- 70 percent said if businesses do not act now, they will be failing their employees and customers (up from 60 percent in 2021)

- 73 percent said if individuals do not act now, we will be failing future generations (up from 62 percent)

Yet our political parties are failing us.

Labour is dithering; National is dissembling; the Greens are turning on each other; the Māori Party is lost in action; and ACT’s fig leaf to cover its deep belief in no action is to argue all we need is an Emissions Trading Scheme.

Thus, it’s amazing we’ve got as far as we have to date. At least we have an overarching legislative framework (the Zero Carbon Act), the first three carbon budgets for the nation (each successively smaller than its predecessor out to 2035), an independent statutory authority to advise and evaluate (the Climate Change Commission) and a so-far skeletal strategic framework for climate action by sectors (the Emissions Reduction Plan).

Many people were involved in those. But one person was the parliamentary leader who made them possible – James Shaw, climate minister and Green Party member. Given his couple of decades working on climate in NGOs and business here and abroad before becoming a List MP in 2014, he knows more about the enormous subject than any other parliamentarian.

Far more importantly, he has had the prodigious political patience and skill to build near-universal support in Parliament for those foundation stones of our climate response. Nobody else in Parliament comes close to his deep knowledge, commitment, or powers of political persuasion.

That one person is so crucial to tackling the biggest issue confronting our country is a measure of how immature our climate response is. Don’t blame our small population. Scandinavian countries of similar size to ours have strength and depth among their climate experts, in politics and across society, honed by years of constructive politics and action on environmental and climate issues.

Moreover, worry a lot about political platitudes. Don’t let National fool you. They talk of being part of the political consensus on climate. But all their statements on it are vacuous. For example, these are its five climate principles, as espoused by Scott Simpson, its climate spokesman, in a news story in April:

- Science-based: Targets and decisions must be based on the best available science.

- Technology driven: We will adopt new technologies to reduce emissions rather than rely on lower economic activity.

- Do what works: People respond best to change when engaged and given policy signals that provide confidence in their short and long-term decision-making.

- Global response: New Zealand will keep pace with our global trading partners.

- Economic impact: We will seek to minimise the economic impact of reducing emissions, especially policies that place an unfair burden on single regions.

Similarly, the most recent entry on the National Party’s website climate page was on May 16. It was only the second item posted so far this year. Simpson hasn’t posted on his party page since last October, and that was on urging KiwiRail to avoid a strike over Christmas.

In the same vein, its caucus economic adviser is Matt Burgess. His last paper for the New Zealand Initiative, a deeply conservative research organisation, published just four months ago, was entitled Pretence of Necessity: Why further climate change action isn’t needed and won’t help.

National’s caucus is singularly ill-equipped in terms of climate knowledge and conviction to be an effective and constructive leader of the opposition. Should the party form the next government, its climate leadership would be ill-informed and inept.

The depressing fact is we are still desperately lacking a committed, constructive and enduring all-party political consensus on climate. But building one in Parliament is immensely difficult, given the swirling political currents.

By far the best way to build one is out in the community, in local climate projects that bring people together, whatever their politics. If very disparate people can collaborate on predator-free projects, as they impressively do, we can do it on climate too.

It’s essential that people of diverse political allegiances work with each other at the flax roots on climate action. By learning from each other, they can achieve common purpose and action, and feed that knowledge and progress back to their parties. Then, hopefully, their parties will be more constructive and ambitious on climate in Parliament.

The capability of parties and their members to respond this way varies widely.

Worst is ACT given its deep philosophical commitment to individuals over community, and thus its limited appetite for collective responsibility and action on anything.

National is somewhat less handicapped by its political instincts but culturally still struggles to reach out to diverse communities.

Labour has a long history of collective action but is still figuring out how to do that in contemporary ways, particularly with younger people and on climate.

The Māori party is effective among its own people but still has a long way to go to engage more widely.

The Greens have two strengths. They are good at helping to build communities around specific issues; and their small caucus is an unusual, and beneficial, mix of community activists and subject experts.

The activists include Marama Davidson, Teanau Tuiono, Ricardo Menéndez March and Chlöe Swarbrick, who is the most impressive. She has shown how to win a constituency seat in Parliament that way, as she did in Auckland Central at the 2020 election.

The experts include Shaw on climate widely, Julie Anne Genter on transport and built environments, particularly in climate terms, and Eugenie Sage on the natural environment and ecosystems, again with a strong climate focus.

But the Greens have done themselves and the country a great disservice by forgetting, hopefully only briefly, that its activists and experts have two complementary but different jobs to do.

The talent and energy of the activists is best directed out in the community. If they do their job well they can help drive grass roots action, and changes in political culture and representation.

The talent and energy of experts is best directed in Parliament. If they do their job well they can build parliamentary support for changes in law, government policy and action, as they have so far, for example, on climate.

If the two sides of the Green Party can figure out how to work together again – and in much better ways - they will have far more impact on politics and progress.

If they can’t, they will makes themselves irrelevant; and Aotearoa would be worse off, dogged more than ever by its dysfunctional party politics.