The 2022 World Series turned on the most important element of hitting today. The defining moment arrived in the fourth inning of Game 5: The series stood tied at two games, and the game stood tied at one run. The series would diverge depending on which team scored the next run. Astros rookie shortstop Jeremy Peña stepped into the box against Phillies starter Noah Syndergaard.

What happened next defines how much the classic pitcher-batter confrontation has changed and how teams evaluate what makes a great hitter has changed. For a hundred years the fastball was the ultimate measuring stick. Pitchers tested rookies on whether they could hit “major league velocity.” They established their fastball so they could blend in their appropriately named “secondary” pitches. They threw challenge fastballs when behind in the count.

No more. These are the new rules of engagement:

- Fastballs, for the first time in the history of the game, no longer account for the majority of pitches (48.6% last year, not including cutters).

- Most breaking pitches are not in the strike zone (56%).

- Hitters bat .121 when they chase breaking pitches out of the zone, with one hit for every 19 times they try to hit one.

Rookies like Peña already have seen elite velocity in the minors. They can train off high-velocity pitching machines that make the average big league fastball of 93.7 mph look like BP. The true measuring stick now: swing decisions, especially against breaking pitches that wind up out of the strike zone, known as “chase breaking pitches.” The quality of those swing decisions is how young hitters are being evaluated.

“I think if you break it down,” says Mariners hitting coach Jarret DeHart, “hitting in the major leagues today is about hitting somebody’s best fastball and hanging breaking ball. If you lay off the chase breaking ball, you’re going to be pretty good.”

Careers can be made or lost based on swing decisions against breaking balls. So, too, can a World Series.

Syndergaard began the at bat with the pitch of the decade: a slider. Major league pitchers have increased their slider use for 13 consecutive seasons, reaching 21% last season. Sinkers historically outnumbered sliders—until 2019. Now it’s not even close. Following analytics that reveal an average slider is harder to hit than a great sinker (and has more swing-and-miss to it), the average game has 15 more sliders than sinkers.

This wasn’t a garden-variety slider Syndergaard threw. It was a museum-quality oil painting, as sliders go. It tracked the outside edge of the plate at 88 mph; Peña read it as a fastball and swung. But just as his barrel came around, the pitch darted away from him and outside the strike zone. (Classic chase breaking ball.) Peña missed it. Syndergaard had perfectly executed the Greg Maddux definition of pitching: “Make the balls look like strikes and the strikes look like balls.”

Syndergaard decided on a curveball next. It is the worst of his five pitches; he throws it once every 10 pitches to right-handed batters. This one was so bad—hanging in the middle of the zone—that Syndergaard flinched as Peña took a whack at it. Too anxious, Peña pulled it foul.

Dale Zanine/USA TODAY Sports

Given a reprieve, Syndergaard went back to a slider. It was another beauty, once again presenting as a strike on the outside corner before snickering its way off the plate. It was everything the pitcher wanted to end the at bat in his favor. But Peña recognized the chase breaking ball this time. Even at 0-and-2, he did not take the bait. He never started his bat.

That swing decision would help decide the World Series.

Taking note of Peña’s pitch recognition, catcher J.T. Realmuto called for a sinker inside, inversing pitch type and location. Peña took that one, too, for ball two.

Now what? Peña had taken the slider away and the fastball in, both while on balance. Those were two elite swing decisions with two strikes. Realmuto and Syndergaard went back to the righthander’s fifth best pitch: the curveball.

Uh-oh. This one was as bad as the 0–1 curveball. Another hanger. Middle of the zone. Peña did not miss this one. He popped it 350 feet to left field, a few rows into the seats, for a 2–1 lead. Houston held the lead to win, 3–2, then won Game 6, 4–1, to close out its championship. Peña was named World Series MVP.

How did we get here? Steadily, at least once the pitch-tracking service known as Statcast changed the way baseball decision-makers looked at the game. It took a generation of pitching coaches who questioned the “establish your fastball” ideology and who absorbed data that undeniably encourages more spin. Technology led to pitchers fine-tuning the spin and shape of their breaking pitches in pitching labs. Most importantly, hitters dictated that pitchers should spin the ball more. Last year, in what is a typical pattern, batters hit worse against an average 84-to-85-mph slider (.211) than a fastball at the extreme velocity of 98 mph or more (.217).

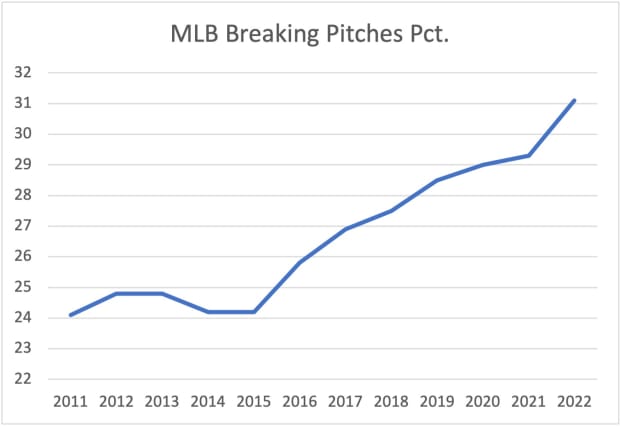

Here is a look at the steady increase in spin ever since Statcast came along in 2015. Breaking pitches have increased from roughly one out of every four pitches to one out of every three pitches.

Have hitters adjusted to seeing more spin? No. They struggle against and chase spin at about the same rates. See for yourself:

Batting vs. Breaking Pitches

That leads to an important question for teams: If making good swing decisions against spin is the most important element in hitting today, is that a skill that can be learned, or is it mostly an innate trait?

“Welcome to the big leagues, Julio Rodríguez.”

A generation ago, pitchers would have made that statement by seeing if the rookie could hit their fastball. No more. Rodríguez, the Mariners’ center fielder, saw more breaking pitches in his first month in the big leagues last year than any hitter in baseball (157, or 49%). Here’s a quick thumbnail of how hitting has changed for rookies:

Fastballs Seen, First 20 MLB Games

Rodríguez hit .167 against spin in April and .209 overall that month with no home runs. Unlike fastball velocity, hitters simply will not see the same quality of breaking pitches in the minors as they will in the majors.

“The breaking ball approach, we specifically saw him develop in that area over the course of the year,” says DeHart, when asked how Rodríguez overcame the slow start. “He has no problem handling the best fastballs.

“Through the minor leagues, he was always a pretty good breaking ball hitter. He would swing at anything he thought he could hit, which led to some chase out if the zone. But you’re not penalized as much there as you are in the in big leagues because the quality of the breaking ball is not as good.

“Throughout the year he started to see so many of them he began to adapt. Once he learned how hard they were to hit, he began to lay off the chase breaking ball and learned how to hit the hanger. The power really showed in the second half. It was a gradual process.”

Rodríguez slugged .609 against spin in the second half, trailing only Nathaniel Lowe, Aaron Judge, Manny Machado, Mike Trout, Eduardo Escobar and Pete Alonso.

But consider Javier Báez of the Tigers. There has been no improvement. Now 30 years old and entering his 10th season, Báez still makes the worst swing decisions against spin. He saw the most breaking pitches (42.5%) and chased them the most (50.2%), including an absurd 62% chase rate with two strikes. (The average MLB two-strike chase rate against spin is 41%).

Every year since 2016, Báez swings at more than half the two-strike breaking balls that are not in the zone. There is no discernible improvement on his two-strike chase rate against breaking balls, starting with ’16: 67%, 61%, 57%, 59%, 55%, 64%, 62%.

Watch MLB games live with fuboTV: Start a free trial today!

Before the Red Sox drafted Mookie Betts, one of their scouts pulled him out of lunch at Overton High School in Nashville to play a laptop game that simulated swing decisions. The franchise had purchased propriety rights to the program from a Boston-area developer and tried it on its major league hitters. The idea was to find a way of measuring how quickly a hitter made swing decisions and how accurate they were. The Red Sox were blown away by the results from Betts; he graded at the level of established major league stars such as David Ortiz and Dustin Pedroia.

Sure enough, Betts has proved to be one of the best hitters in baseball when it comes to swing decisions. He ranked 22nd in lowest chase rate in MLB last season. His career chase rate of 20.2% is well below the major league average of 28.4% over his career.

Kevin R. Wexler/NorthJersey.com

Today’s hitters can train their eyes by watching hours of breaking pitches on virtual reality headsets. They can hit off pitching machines calibrated to the exact velocity and break of the starting pitcher that night.

Does such training work? It can, but only a little. Only three hitters last year improved their chase rate by more than 5%: Andrew Benintendi, Kolten Wong and Jesse Winker. Benintendi posted a career high OBP. Wong reached career highs in homers and OPS+. Winker set a career best in walk rate but had an otherwise miserable season.

The best hitters when it comes to swing decisions have that skill at an early age, like Betts and like Juan Soto, the king of swing decisions. Soto chased only 19.9% of pitches outside the zone last year, the best in baseball.

Nationals scout Johnny DiPuglia saw the plate discipline in a teenage Soto the way others might see foot speed or arm strength.

“His eyesight—it’s ridiculous,” DiPuglia says. “Barry Bonds’s eyesight was something like 20/10. Pedroia was like 20/8. Guys like that can see the ball hit the ground and see the dirt come off the ball. It’s like in any sport every once in a while you get a guy that’s just different.

“You can tell he has good eyes by the way the ball hits the barrel. A lot of guys, when you pick up their bat and see where the ball hits [it], and it’s all the way from the knob down the bat. This guy wore out the barrel. It was unbelievable. When you’re playing golf and that one guy has that one part of the cavity that’s worn out? He’s got good hand-eye coordination.”

The average big leaguer chases breaking balls 31.4% of the time. Soto is more than twice as disciplined, at 14.5%. Other hitters with great swing decisions against chase breaking pitches include Max Muncy of the Dodgers (15.5%), Matt Chapman on the Blue Jays (18.6%) and Judge of the Yankees (20.9%).

Since 2016, Paul Goldschmidt of the Cardinals has seen the most breaking pitches out of the zone but chased them only 22.7% of the time, well below the MLB average of 31.1%.

How do you win an MVP? You consistently make good swing decisions on the chase breaking pitches. Both MVPs, Judge and Goldschmidt, ranked in the top five in seeing the most chase breaking pitches, but both pulled the trigger far less often than the major league average.

Most Breaking Pitches Seen Out of Zone, 2022

The ultimate test of swing decisions is the two-strike breaking ball, and it’s a test administered with increasing frequency. (They have gone up 22% since 2015.)

Hitters are a prideful bunch. They especially hate striking out on a pitch on which they didn’t swing. Pitchers know this and prey upon it, which is why 58% of all two-strike pitches are not in the strike zone. Last season 77% of all strikeouts were on swings. Of those, 61% were on pitches out of the strike zone.

With pitchers throwing more chase breaking pitches, maintaining strike zone integrity with two strikes becomes even more important. Soto and Báez are at opposite ends of the swing decision spectrum. Soto saw 146 two-strike chase breaking pitches last year and swung and missed at only 10 of them. Báez saw 213 of them and whiffed on 65 of them.

Nobody struck out swinging at a chase breaking ball more than Báez. And who was number two on that list of infamy with 56 whiffs on chase breaking balls? None other than the Astros’ Peña.

Postseason pressure is real. The stakes are higher. The quality of stuff on the mound is better. The scouting reports are more detailed. Pitchers are more careful. The game changes. We see that in pitch selection and swing decisions:

Pitchers throw more breaking pitches in the postseason and keep them out of the strike zone more. Hitters chase more. Swing decisions get tested even more in the postseason, which is why what Peña did against Syndergaard was even more amazing.

Peña is not a very good hitter when it comes to swing decisions; he was in the bottom 4% in walk rate last season and bottom 8% in chase rate. Only five hitters chased more two-strike breaking balls, and only Báez and C.J. Cron did so at a higher rate than his (53.3%).

When Syndergaard threw that nasty 0–2 chase slider, the odds were greater that Peña would chase it rather than take it, especially in a pressure-packed spot. In the postseason, Peña had swung six times at nine two-strike chase sliders, going 0-for-6 with four strikeouts.

This time, somehow, he held up with a perfect take. Then, when he saw the only fastball in the sequence, he held up again. Only then, with the count, game and series all square, and having given an unlikely master class in swing decisions, did he change history.