The opening shot of Bird, Kent-born director Andrea Arnold’s new cinematic masterpiece, is a clue that can help to unlock the confounding film that will follow. We see two birds swooping through the air, coursing through a pastel blue sky – but our view is partially obscured by an ugly metal fence. The image is also being snapped by 12-year-old Bailey (played by screen newcomer Nykiya Adams), a fellow Kent native who spends much of the film taking pictures on her smartphone.

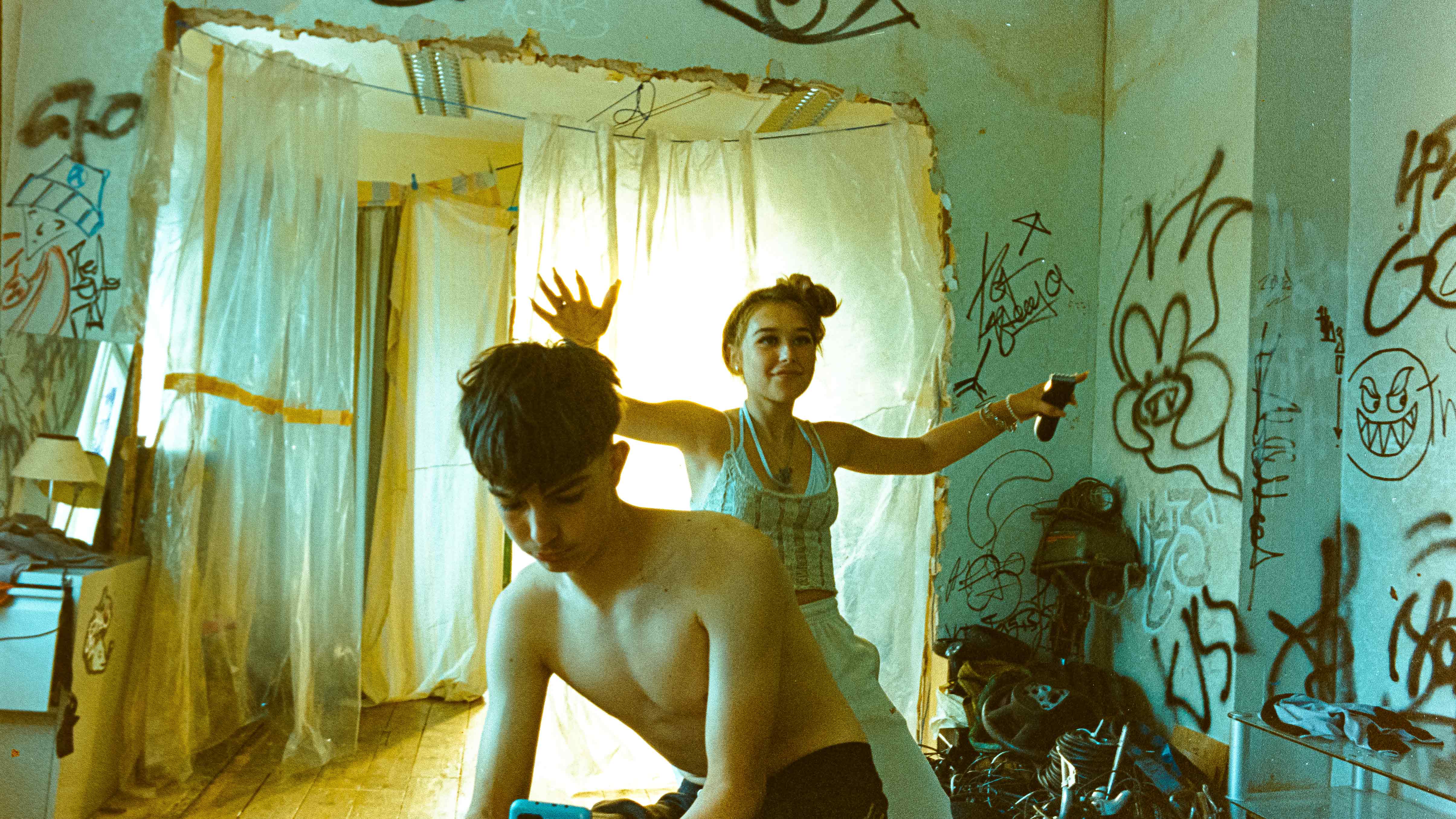

Living in a graffiti-strewn squat with a feckless Dad (Barry Keoghan) and her disaffected half-brother, Hunter (Jason Buda), Bailey clearly feels out of control. Her father’s similarly disaffected friends come and go as they please and he’s about to marry Kayleigh (Frankie Box), a woman he’s known for a few months – never mind his daughter’s disapproval. So, like many a photographer before her, the 12-year-old captures images to try and make sense of her world, to create a version of it that she can contain.

Mirroring the birds behind the metal fence, she will also find a way to soar above her prosaic surroundings. One morning, out in lush fields away from the violence of the town, she encounters a man who calls himself Bird (Franz Rogowski). He says that, having grown up locally and moved away long ago, he’s trying to reconnect with his family. Slowly, over the course of the film, Bird reveals himself as a magical figure who can apparently bend reality. This initially manifests with relative subtlety, before the full extent of his abilities are revealed.

Critics haven’t quite known what to make of Bird, Arnold’s sixth feature film and the latest proof of her status as a bonafide modern-day auteur. In an age where critical consensus seems to have become the norm, the picture has proved curiously divisive. There have been one or two raves, but it’s equally been described as “chaotic” and “flawed” and accused of “artful indulgences” that detract “from its purported authenticity”. This is perhaps an indication of Bird’s weird power and a reluctance to believe that the director could have combined social realism with magical realism in such an unprecedented way.

63-year-old Andrea Arnold’s entire career has been similarly audacious. After a trio of short films (the third of which, 2003’s Wasp, took that year’s Oscar for Best Live Action Short Film), she released her debut feature, 2006’s Red Road. Mostly shot according to rules outlined by Dogme 95 (Lars Von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg’s 1995 filmmaking movement that, among stipulations, decreed filmmakers must use handheld cameras), this was an aching depiction of grief that cemented her essentially optimistic outlook.

Arnold followed Red Road with further social realism in 2009’s acclaimed Fish Tank, set on east London council estate, before pivoting to period drama with 2011’s Wuthering Heights, an experimentally gritty adaptation of Emily Bronte’s novel. After these most British of projects, she naturally made an all-American road epic: 2016’s American Honey starring Riley Keough and Shia Labeouf, her first true masterpiece.

Bird might feature a call-back to American Honey in a shot of Bailey floating in water as a brief respite from the challenges she faces, just as Star (Sasha Lane) did in the earlier film, but it’s arguably closer to Red Road in Arnold’s oeuvre. This is a film that depicts a brutalist, apparently cruel world, but offers ever-brighter flashes of hope and magic. What’s different is that, this time, the magic is literal.

Cinema has, successfully or otherwise, previously combined depictions of urban decay with fantastical elements: see Ryan Gosling’s 2014 directorial debut Lost River. Yet Bird flies alone as a British social realist film that explodes its naturalistic world with such rainbow-hued streaks of magical realism. A review of Fish Tank described Arnold as “Ken Loach's natural successor”. With her new film, she transcends that restrictive description like the birds dipping and diving above the metal fence in its dreamy opening shot.