Williams-Sonoma Inc. (WSM) CEO Howard Lester was skeptical.

Very skeptical.

It was 1997 and Pat Connolly, a top executive at the famed home goods retailer in San Francisco, just told his boss that the company should launch its own website.

“I just can’t imagine that people are going to sit in front of the computer and buy our merchandise,” Lester said at the time. “Right now, I think (the Internet) is way over-hyped.”

Though Lester ultimately approved Connolly’s plan, the latter felt the heat.

“If the company’s overall sales (from stores and its catalog) were soft, it was clear people were going to blame e-commerce,” Connolly said.

Today, in a reverse, bizzaro twist, Williams-Sonoma stores, not its online operations, pose the biggest question to the company’s future.

Digital First

Under current CEO Laura Alber’s “digital first” strategy, two-thirds of Williams-Sonoma’s annual revenue of $8.7 billion now comes from e-commerce. And this year, the company plans to allocate 80% of its total capital investments, or $200 million, on its e-commerce operations.

So “what’s the role of the physical stores?” said Brian Kilcourse, managing partner of RSR Research consulting firm. “It’s not quite clear.”

Like most retail CEOs, Alber preaches the vision of an omnichannel business in which e-commerce and physical stores seamlessly complement each other. For example, it’s fairly common now for consumers to pick up or return online orders at a store. And retailers now use stores as mini-distribution hubs to ship internet orders to homes and businesses.

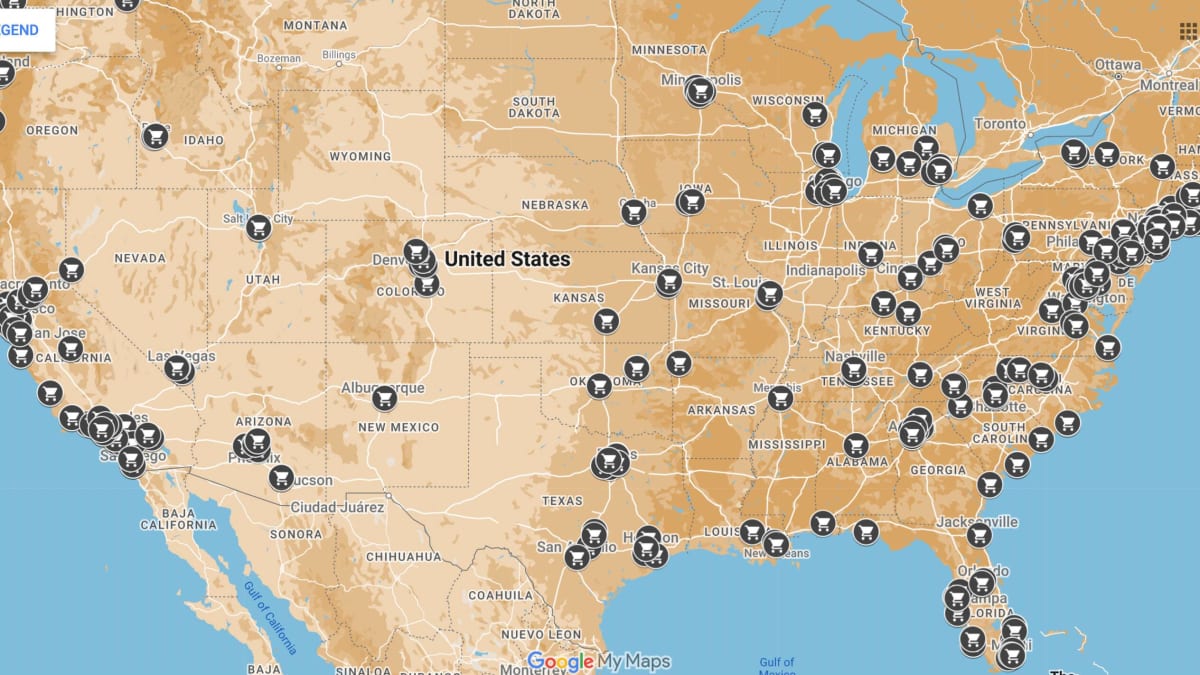

But evidence suggests that Williams-Sonoma lags far behind the industry in this regard. So much so that the company seems more like an e-commerce retailer that just happens to operate 530 stores.

In a presentation to investors last year, the company said omnichannel sales account for less than 5% of its total business. (Interestingly enough, the investor presentation the company released earlier this month excludes this data.)

By contrast, Target Corporation (TGT) says it now fulfills more than 95% of its sales (physical and digital) directly from its stores.

“We have a substantial runway to drive more omnichannel sales,” the Williams-Sonoma presentation said. “We will continue to expand and optimize our omni services, including more dedicated associates for omni fulfillment.“

Nothing can replace stores

What makes Williams-Sonoma’s focus on e-commerce over stores so unusual is the category it operates in. Goods like beds, coffee tables, and arm chairs seem more suited for a physical store where consumers can experience and interact with the merchandise before committing to such higher end purchases.

You can see why Lester was so skeptical in 1997.

The company cites data that shows e-commerce so far has penetrated only 30% of the home furnishings market, far behind consumer electronics (80%), office supplies (72%), and apparel (46%).

But Alber clearly has figured something out. Online sales last year hit $5.7 billion compared to $3.1 billion in 2019, a compound annual growth rate of nearly 17%.

Moreover, Williams-Sonoma has learned how to actually make money selling stuff online. Building a supply chain network to serve e-commerce is expensive and the inevitable returns eat away at profits. Yet the company still generated a healthy operating profit margin of 17.5% last year and nearly 18% in 2021 during the pandemic.

But nothing can replace the intrinsic value of physical stores. Bricks and mortar are the best ambassadors for the brand, Kilcourse said. People also tend to purchase more in stores versus online, he said, a fact that really benefits Williams-Sonoma because their shoppers always plan to buy something when they visit a store.

“People just don’t wander into Williams-Sonoma by accident,” Kilcourse said.

As for omnichannel, stores offer a much easier way to return merchandise than shipping it back to the retailer, he said.

Alber, for her part, insists stores remain crucial to Williams-Sonoma’s strategy.

“You see people with large e-commerce businesses but no stores,” she recently told analysts during a conference call. “You see people who have enormous stores, but they really don't invest much in e-commerce. And we know that the multichannel shopper shops more, and it's the experience they're looking for so they can research online and go sit on the sofa in the store.”

Clicks, not bricks

But unlike retailers like Dick’s Sporting Goods Inc. (DKS) and Burlington Stores Inc. (BURL), Williams-Sonoma has made it clear the company is not interested in expanding its store count. Under its “retail optimization strategy,” Alber says the company is targeting fewer, more profitable stores.

Burt Flickinger, managing director of Strategic Resource Group, a consulting firm in New York, thinks Williams-Sonoma’s “digital first” approach gives the company time to see “where the customer ultimately settles out” as the economy recovers from the global pandemic.

Ideally, the company would rebalance its real estate portfolio towards off-mall locations like lifestyle centers, especially near retailers like Target that score high on shopper safety surveys, he said.

Ultimately, Williams-Sonoma’s journey from a chain of furniture stores to a major e-commerce retailer defies conventional wisdom.

Whereas traditional brick and mortar chains, especially mall-based department stores and apparel shops, have struggled to build e-commerce businesses, the company’s biggest challenge is figuring out what to do with its stores.