An inglorious mess. That is precisely what Bengaluru’s bizarre, chaotic outward expansion has become, despite decades spent articulating the crying need for planned, regulated, controlled growth. How long should the city wait for a Master Plan that really works?

The last such attempt, the Revised Master Plan (RMP 2031) was scrapped two years ago. By all accounts, a new plan would take at least two years. But there is no sign that work on a draft is in the making. Does this mean Bengalureans would have to perennially endure the consequences of random infrastructure projects envisioned with zero connection to what the city really needs?

Tasked with preparing the draft, the Bangalore Development Authority (BDA) had insisted that groundwork on the plan would be taken up on priority. Last year, the new commissioner had talked about drone surveys to identify the residential, commercial, agricultural and other zones, analysing the city’s planning needs for the next 10 years. He had agreed it was a long process and a survey was only the first step.

Moving on from RMP-2031

Approval for the draft RMP-2031 was reportedly withdrawn for not incorporating the recommendations of a Transit Oriented Development (ToD) policy. It also lacked the integration of a Comprehensive Mobility Plan (CMP), prepared by the Bengaluru Metropolitan Land Transport Authority (BMLTA). This legislation was passed well over a year ago, but the Authority is yet to take shape.

In the current vacuum, the BDA has been using the outdated RMP 2015 to approve plans. For the record, RMP 2015 has been blamed for all the havoc triggered by constructions on storm water drains and lake beds. Many policy experts are convinced that the genesis of the floods that had the city in a twister of mobility woes and marooned scores of localities could be attributed to the old plan prepared in 2006.

Problematic old plans

Bengaluru does have a history of Master Plans. But did they really help the city grow in an organised manner? Not really. Planning, as articulated by the 74th Constitutional Amendment, should be a local government function, as urban planner Anjali K. Mohan points out. This bottom-up approach would mean the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) prepares a spatial plan embodying, through the ward committees, socio-economic development as the goal.

The Bengaluru Metropolitan Planning Committee would then provide a framework for such ground-up planning. It would also be tasked with coordinating and collating such efforts across local governments to prevent overlaps and gaps in large infrastructure planning and implementation.

Needed: A bottom up approach

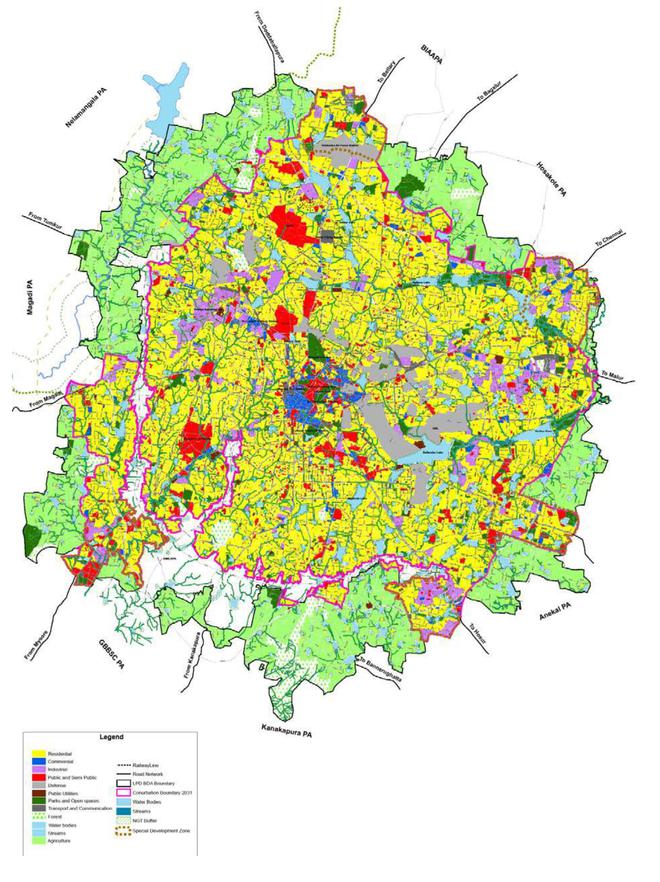

Architect and urban planner Brinda Sastry who was consultant planner for RMP 2015 notes that the now withdrawn RMP 2031 “brought in the critical perspective of building the city’s vision in the regional context. However, it is imperative for the proposed vision of the upcoming Master Plan to include a framework for local area planning, which would provide opportunity to coordinate development initiatives across scales while involving ward level participatory planning.”

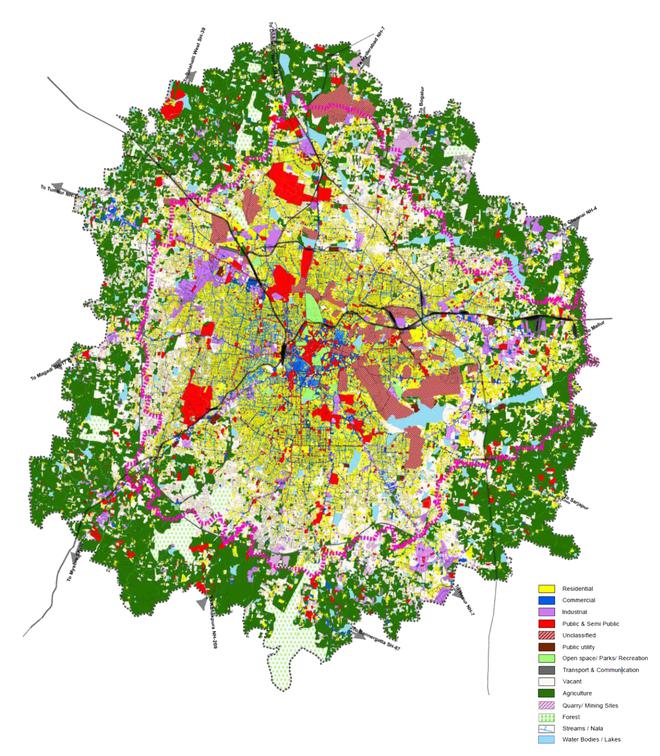

The Bangalore Master Plan 2015, she recalls, had several new perspectives for envisioning the future of the city. “It was the first time that the city’s system of tanks and nullahs were documented using GIS, with the aim to conserve them. Ecologically sensitive areas were zoned for protection. The proposed land use zoning plan was responsive to the development trends while recognizing the prevailing traditional urban patterns of the city,” elaborates Brinda.

Specific projects and programmes were proposed in the Planning District report for implementation at a local scale. “However, the plan was not implemented as envisioned and violations of the proposed zoning led to unmanageable consequences. Provision for periodic update of the Plan and frameworks for conducting local area planning exercises were lacking. It required coordinating future projects and plans across various departments in the government and allocation of funds for implementation.”

The Master Plan is mandated to be revised once every 10 years as per the provisions of Section 13D of the Karnataka Town and Country Planning Act, 1961. RMP 2015, prepared and approved on June 25, 2007, was in force when the draft for the 2031 plan was prepared.

Violated with impunity

Master plans have been violated with impunity in the past. For instance, the areas marked as agricultural zones in the RMP 2015 have seen massive land use changes, with authorized and unauthorised developments mushrooming. Road networks are rarely integrated, triggering severe traffic gridlocks.

The 2007 expansion of the old Bangalore Mahanagara Palike (BMP) to a 198-ward Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) only added to the chaos. Seventeen years after that transition, vast swathes of the city’s outer areas are still without a proper drainage system, well connected roads, parks, bus connectivity, street lights and other basic amenities.

‘Revisit plan every five years’

“A new master plan, whether RMP 2041 or 2051, should be more dynamic. What we need more are guiding principles, and the plan must be revisited on a five-yearly basis,” feels urbanist V Ravichandar. While it can have long goals and vision, the plan must be dynamic and open to readjustment.

Bringing all agencies linked to the city on board is one way to keep violations at bay, he notes. “It should have a lot more ground up inputs, including from citizens. It needs to ensure that all agencies are part of the process. Currently, the BDA makes the plan and others are not bothered.”

The city’s rapid population growth, exasperated by a grossly inadequate public infrastructure, has had the planning process play catch up. By one estimate, the city’s population grew by a whopping 38% from 1991 to 2001, adding another 47% in the decade thereafter. Although the 2011 census put the city’s population at 8.4 million, Bengaluru is to be home to 12.5 million by 2025.

The lack of a consultative process in preparing the master plan is learnt to have directly impacted RMP 2031. Although non-integration of ToD and CMP were cited as factors that led to the plan’s scrapping, objections from landowners and political players on the demarcation of green zones were also a key deciding factor.

Going beyond surveys

“Updating the master plan is definitely important because we are now working off 2015 survey data. A lot of development has happened since then which is not in alignment even with that master plan,” notes urban mobility activist Sathya Sankaran. “This shows we don’t just need to do surveys, we need to know the problems we are trying to fix,” he says.

The master plan, he reminds, “should not be relegated to just drawing lines on a document by some consultants who don’t understand the nature and systems of the city.”

From a mobility perspective, he draws attention to Bengaluru overtaking Delhi as the city with the most number of car registrations. “Without the BMLTA being constituted and making the ToD plans for the city, the master plan will be relegated to drawing lines on the map based on individual transport agencies working on their independent financial indicators and plans,” elaborates Sathya.

A business as usual approach would mean Bengaluru will continue to lag behind on efficient mass movement of people using public transport, cycling and walking, he cautions. The time is now to think ahead and plan for sustainable urban development for the city. Grand plans such as the tunnel roads are just not the way forward.