Australia is in a domestic violence crisis, the prime minister has declared, after a spate of alleged murders of women put the issue at the top of the political agenda. Following a national cabinet meeting on Wednesday, when Anthony Albanese and state and territory leaders sought to come up with solutions, several concrete proposals have been made. The federal government vowed to permanently establish a financial support program for victim-survivors leaving violent relationships, and to take action to curb harmful content online.

How did we get here?

Violence against women is a perennial problem globally, including in Australia, but in recent weeks the country has reached what some have called a “tipping point”. The alleged murder of 28-year-old Molly Ticehurst by her partner shocked the nation, and has renewed debate on whether bail laws are sufficient.

Ticehurst is far from the only woman allegedly killed by their partner this year. Last week, West Australian police charged a 35-year-old man with the murder of Erica Hay, a mother of four. The man, who police allege was known to Hay, has also been charged with one count of criminal damage by fire, after he set their Perth home on fire. Last Tuesday, 49-year-old Emma Bates was found deceased in her home.

According to data interpreted by Counting Dead Women, 28 women in Australia have been violently killed so far this year, as of April 30. Data released by the Australian Institute of Criminology on Monday showed a 28% jump in intimate partner homicide in 2022-23, compared with the year before. Previously, such killings had been in decline.

“It is a sizeable increase, and to some extent, one that we weren’t expecting,” Samantha Bricknell, research manager at the Australian Institute of Criminology, told CNN.

Where is the national conversation at?

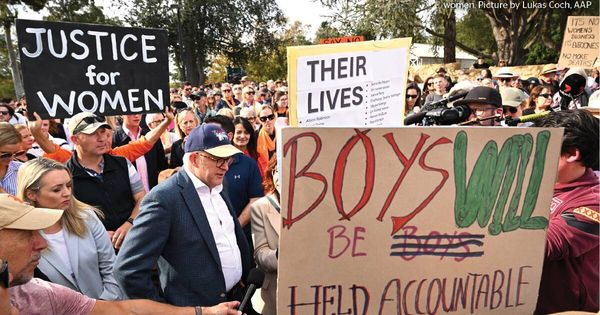

There have been marches and vigils across the country, including events in several major cities last weekend. In the opinion pages, debate has raged about whether violence against women should be considered terrorism, and about whether there is enough funding for anti-domestic violence services. Advocates such as Jess Hill, author of the award-winning book on domestic abuse See What You Made Me Do, hasve argued Australia needs to rethink methods for preventing domestic violence.

State and territory police ministers will meet with federal Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus in Canberra on Friday to discuss law enforcement strategies. Meanwhile, the ACT Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and young people commissioner Vanessa Turnbull-Roberts has argued authorities shouldn’t rely on punitive measures alone — rather, she writes, “It is crucial to establish comprehensive support systems for survivors, including access to trauma-informed care, counselling [and] legal supports.”

What’s the federal government’s response?

The national cabinet meeting earlier this week led to several announcements, including permanent funding for a program called Leaving Violence. Established as a trial by the former Morrison government in 2021, the program gives money to people fleeing violent relationships.

The program was due to end in January, but Albanese has vowed to make it permanent, investing $925.2 million over five years. Under the program, eligible victim-survivors can get up to $1,500 in cash and up to $3,500 in goods and services, “as well as safety planning, risk assessment and referrals to other essential services for up to 12 weeks”, according to yesterday’s announcement.

Will it help?

Advocates say any extra funding is welcome, but many hope the government will go further.

La Trobe senior lecturer and sexual violence prevention researcher Jess Ison said individual $5,000 payments would not go far enough.

“We know the evidence shows that one of the really key reasons women don’t leave [a violent relationship] is because they don’t have secure housing, and that’s particularly true if they have children, if they have pets,” she told Crikey.

“When we work in this area, we’re so used to taking bread crumbs, and particularly those doing frontline work are chronically overworked and underpaid. Of course it’s great, but we need so much more.”

Full Stop Australia chief executive Karen Bevan said the funding was “a step in the right direction, although we would like to see the government go further”.

“We welcome ongoing funding for the Leaving Violence program. This program puts resources directly in the hands of women and children leaving violence, supports healing and recovery and provides victim-survivors with an opportunity to re-establish their independence,” Bevan said in a statement.

How will the government limit harmful online content?

There were two different initiatives announced relating to harmful online behaviour. The government has committed to trialling a system whereby access to online pornography would be age-restricted. The pilot will be funded in the May budget and aims to “identify available age assurance products to protect children from online harm, and test their efficacy, including in relation to privacy and security”.

The other initiative is to criminalise so-called deepfake pornography. A statement from the government said there would be legislation introduced “to ban the creation and non-consensual distribution of deepfake pornography”.

Will the age restriction technology be effective?

Cyber experts have limited hope the government will succeed in shielding children from online pornography. Former eSafety commissioner Alastair MacGibbon said, in theory, accessing adult content would be “similar to getting into a pub”.

“Is it possible to verify a person’s likely age? Yes. Do I think people could get around that tech? Of course. That’s my biggest concern,” he told ABC’s RN Breakfast radio program.

“Inaction in this modern environment has led us to the place we are now, which is a terrible place of complete lack of control on the internet. [But] let’s give it a go. Do I think it will fail? Likely. But let’s have a crack.”

How about criminalising deepfake pornography?

Asher Flynn, associate professor of criminology at Monash University, said criminalising non-consensual sexual deepfake imagery would likely help reduce violence against women.

“It sends a clear message that this form of abuse is not acceptable behaviour from a social standard, and helps reiterate that people, women in particular, are not objectified,” she told Crikey.

“It is also likely to impact on the accessibility of digital technologies that are designed purely for the purpose of generating and creating sexual and nude deepfake images. A quick Google search can bring up thousands of sites where you can get access to paid and free technologies that will create a deepfake image. By criminalising this act, it will reduce the ease, accessibility and availability of these tools, meaning that it is harder to create the images in the first place.”

She said such a law would put Australia at the forefront of global efforts to tackle AI-generated harmful content.

“There are very few jurisdictions that capture the non-consensual creation of sexual deepfakes … Victoria is currently the only Australian state where the non-consensual production or creation of a sexualised deepfake of an adult is captured under law. So Australia will be again leading the way in responding to the harms of this form of technology-facilitated violence.”

If you or someone you know is affected by sexual assault or violence, call 1800RESPECT on 1800 737 732 or visit 1800RESPECT.org.au. In an emergency, call 000.

For counselling, advice and support for men in NSW, Victoria and Tasmania who have anger, relationship or parenting issues, call the Men’s Referral Service on 1300 766 491. Men in WA can contact the Men’s Domestic Violence Helpline on 1800 000 599.