Improvements in living standards over generations have been taken for granted in recent history, but these days young people are looking worse off than their parents in one major area: wealth.

Income and wealth have evolved at very different rates in the UK in recent decades, mostly due to sky-rocketing house prices. As a result, millenials and those in younger age groups are much less likely to be on the property ladder by their thirties than their parents. This has significantly restricted younger people’s prospects for future social mobility.

The last 60 years have seen large increases in income inequality in the UK, but most of this change occurred in the 1980s, and on most measures income inequality has been relatively steady over the three decades. House prices and other assets have been growing in value for decades, but this has benefited all property owners and so inequalities in the relative amounts of wealth held by rich and poor have not changed drastically as a result.

But, as recent findings from the Institute for Fiscal Studies Deaton Review of Inequality show, the key change in economic inequality in the UK has been the rising importance of wealth relative to income. This has significantly shifted the balance of economic power between the generations.

This article is part of Quarter Life, a series about issues affecting those of us in our twenties and thirties. From the challenges of beginning a career and taking care of our mental health, to the excitement of starting a family, adopting a pet or just making friends as an adult. The articles in this series explore the questions and bring answers as we navigate this turbulent period of life.

You may be interested in:

Entrepreneurs know that failure is sometimes necessary – here’s what we can learn from them

Quiet quitting: why doing less at work could be good for you – and your employer

Since 1995, average house prices in the UK have risen from £56,000 to over £290,000 by August 2022. This huge growth (which went into a temporary reverse after the 2008 global financial crisis) has far outpaced general price inflation. The price of other assets, such as equities, has also risen during this time, boosted in part by a period of very low interest rates over the last decade. This has allowed large proportions of the population to build up significant wealth because around 65% of UK households are homeowners.

On the other hand, a sizeable minority of the population – those that do not own property or other assets – has almost no wealth at all, and will have gained nothing from this period of huge wealth accumulation. As a result, even though the proportion of wealth owned by richer people hasn’t changed much, the size of the gap between the haves and the have-nots has grown.

Earnings have stagnated

But while wealth has soared, earnings from work have stagnated since the Great Recession of 2008. The average worker’s real (inflation-adjusted) earnings haven’t increased at all during this time, which means their nominal earnings (not adjusted for inflation) have not risen any more than prices. Total household disposable income has also grown slowly, which makes it harder for people to become more wealthy by earning and saving.

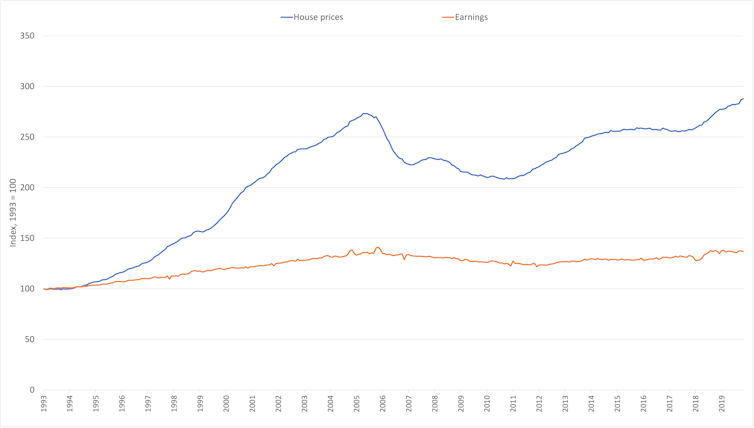

The gap between the middle and the top of this wealth distribution grew from 10 years’ worth of earnings to almost 16 years in the decade after 2008, making it harder to climb the wealth ladder. And even before that, earnings were growing more slowly than house prices. Since the mid 1990s, average earnings (adjusted for inflation) grew by around 37%, while average house prices grew by 188%, meaning they almost tripled in value.

The growing gap between earnings and house prices

This means that saving for a deposit and earning enough to qualify for a mortgage has become much harder for recent generations, for reasons unrelated to excessive consumption of avocado on toast. More than 60% of those born in the 1950s and 1960s were homeowners by age 30, but only 36% of those born in the 1980s were.

Addressing the wealth gap

The combination of rising wealth and stagnating and unequal incomes means older people own increasingly larger shares of wealth, threatening the historic pattern of each generation being financially better off (on average) than the last. Younger generations must rely more on inherited wealth, rather than climbing the wealth ladder with their own earnings. This puts those whose parents and grandparents with little wealth to pass on at an increasing disadvantage. It also risks creating a crisis of worsening social mobility.

The need to tackle inequalities in income and wealth has been a key dividing line in British politics in recent years, both within and between the main parties. But people are likely to find these income and wealth inequalities far more worrying as they become more entrenched and start to threaten social mobility.

The economic outlook has become increasingly uncertain. Without fundamental improvements to productivity to facilitate greater earnings growth, and an increase in the supply of housing, it is difficult to see the recent trends of a growing wealth gap and stagnating incomes coming undone any time soon.

Tom Wernham works for the Institute for Fiscal Studies.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.