“I didn't start out with any funding, I didn't have any investments, I didn't spend all of my money on one big project,” David Gilbert, founder of Wadjet Eye Games, maker, and publisher of point-and-click adventure titles, tells me. “I started with a little game I could afford to make, and it earned a little bit of money. I made another game that earned a little bit more, and I was able to grow very slowly from there. This wasn't my big plan; that's just how I worked.”

Gilbert and I aren’t talking about the current state of the industry; we’re talking about how he started his company in 2006 and has made a living for 18 years creating games that appeal to a small audience. But we didn’t ignore the backdrop of layoffs driven by companies who over-extended, over-invested, or put shareholders' profits ahead of sustainability. It was a few days after we spoke that Microsoft laid off 1,900 staff across its Xbox division and announced it had passed a $3 trillion valuation.

“My games don't take the world by storm, but enough people know about them,” Gilbert tells me. “I have a number of dedicated fans, and the games continue to earn my living. I'm very happy with that. The biggest fear I have is that it will go away one day if I over-invest in something.”

Hobby to profession

Gilbert loved games growing up, playing adventure titles on his family’s Apple II computer, learning to program in Beginners' All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code (BASIC), and – “like every other nerd back in the late ‘80s” – even made a Star Trek adventure game. But it wasn’t until he came back to the US from a year abroad that his hobby turned into a living.

In 2006, Gilbert was returning to New York after a job teaching English in South Korea and traveling in China. He had no clear idea of what to do for a living. Throughout his 20s, he had worked office jobs in corporations and in the garment industry, but nothing had stuck, and those weren’t the kinds of jobs he was keen to return to.

Even though Gilbert still made point-and-click games in his spare time as a way to “creatively vent,” using software called Adventure Game Studios (AGS), it wasn’t as a side hustle; it was a hobby. “I was able to just put a game on the AGS forum, and bam, people were playing it and giving me feedback,” Gilbert says. “That immediacy, the positive feedback loop, it's my dopamine hit.”

Even while traveling in China, writing game ideas in his notebook, all the time thinking, “'Gee, what should I do with my life now that this gig in Korea is over?'” Gilbert says he never thought, “Oh, I should write games [for a living].”

While in Korea, Gilbert had rented out his apartment, and the lodgers still had a few months on the place when he came back to the US, so he moved back in with his parents. “There’s nothing like being almost 30, living with your parents, and not having a job.”

At a loose end but wanting to be busy, Gilbert worked on a game to enter into an Adventure Game Studio monthly jam. These regular competitions stoked creativity in the community, keeping the forums active. There was no prize money attached, just kudos to earn among like-minded folks.

The game Gilbert made was a detective game, like many adventure games, but it had an unlikely protagonist: you play Russell Stone, the Rabbi of a New York synagogue.

When I came back from Korea, I wanted to reconnect with that part of myself. So I wrote this game

David Gilbert

The game Gilbert made was a detective game, like many adventure games, but it had an unlikely protagonist: you play Russell Stone, the Rabbi of a New York synagogue.

The idea for the game had come to Gilbert while he was in Korea, and faced, for the first time, being a minority. “I took being surrounded by other Jewish people for granted,” Gilbert says. “I've never been particularly religious, but South Korea was the first time I was acutely aware of being Jewish. Not only wasn't I around any Jewish people, but people didn't know what it meant [to be Jewish], or they'd never met one. There was this one guy, another Westerner like me, we were out for dinner, and he said, 'Wow, they really Jew-ed us on the guacamole.' When I came back from Korea, I wanted to reconnect with that part of myself. So I wrote this game.”

In The Shivah, Rabbi Stone is investigating the death of someone who used to be a member of his synagogue. The two parted on bad terms, but the police tell him the victim left Stone $10,000 in his will.

Gilbert completed the small game in less than a month, submitted it to the contest, and it won. Players had liked his previous games, but the win, combined with the fact he had some savings and was between jobs, caused something to click for Gilbert: “I couldn’t envision doing anything else.”

Leaving the bubble

Gilbert had seen other Adventure Game Studios developers try and fail to turn their freeware popularity into a career. “The community was tight-knit,” Gilbert says. “The challenge when you decided to sell something was to expand beyond that little community.” One of the first AGS games sold commercially was a superhero parody called The Adventures of Fatman. It went on sale in 2003, and its developer SOCKO! Entertainment closed down within the year. “I think he got disillusioned very fast because he had a lot of trouble selling it,” Gilbert says.

The problem with those games, as Gilbert saw it, was that they were large and took years to develop. After winning the AGS competition in June, Gilbert spent just two months expanding The Shivah, adding puzzles, improving the art, and bringing in friends from his improv group to voice the dialogue, and then he released it, selling copies of the game through a website his brother-in-law set up for him.

While sales weren’t huge, when added to his savings, Gilbert had enough money to work on his next game for about six months. He completed it in four.

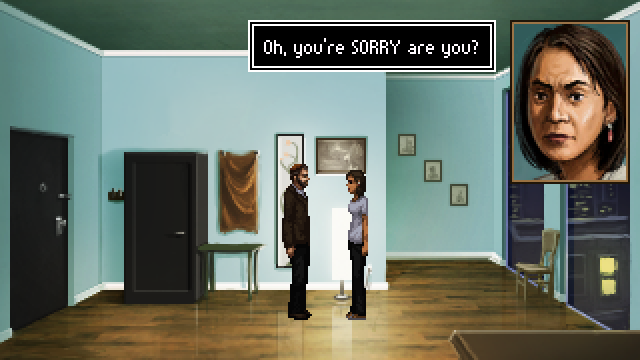

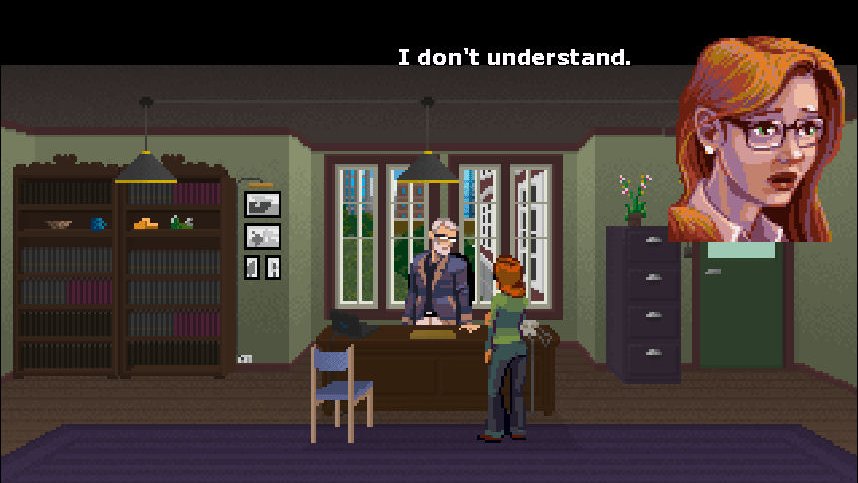

The Blackwell Legacy is an adventure where you play a New York writer who becomes a private investigator after she develops the ability to see and speak with the dead. Gilbert had explored the idea in an earlier freeware game called The Bestowers of Destiny, but now the game was bigger, the art was better, and, as with The Shivah, he brought in voice actors to make the game seem larger than its freeware roots.

“For my first couple of games, I brought in friends and actors who were willing to work for free or for pizza,” Gilbert says. Living in New York, he knew of lots of people who were up for taking part in projects. When working on a later game, he went to a play directed by his friend Abe Goldfarb, who voiced Rabbi Stone, and from the actors “cast half of Blackwell Unbound by attending this one play.”

As Wadjet Eye Games has grown, Gilbert no longer approaches casting voice actors as hobbyist work – “You can't do some big epic thing and expect people to work for free or cheap” – and even casts and directs voice actors in other games he’s involved in. In those first days, though, it was just fun to get together with friends and put on voices.

There were trade-offs to making The Blackwell Legacy that Gilbert quickly admits, “It's the jankiest of the five games for sure. People still find bugs in that little game almost 20 years later.” In part, those bugs came from how sleep-deprived he was. “I remember, towards the end, running out to get some coffee late at night and thinking: 'Okay, I know I'm not sleeping tonight. I don't think I slept last night... did I sleep the night before?' My brain was all over the place. I never want to go through that again.”

But Gilbert also says: “If I had spent years working on my first games, who knows where I'd be now?”

In 2006 there were fewer people making games than there are now, certainly as independent developers. You weren’t competing against the torrent of releases you see on Steam every day, but then you also weren’t able to get your games onto Steam anywhere near as easily. It wasn’t until 2013, with Steam Direct, that the company offered a way for developers to get their games onto Steam without an invitation, so back in those early days of Wadjet Eye Games, earning a living as a game developer was a very different picture.

One advantage was when someone bought the game, I got the money right away. I didn't have to wait until Steam or GOG paid me

David Gilbert

Many people were wary of using their credit cards online, Gilbert tells me, so customers would often send him money in the post, sometimes in foreign currencies. He remembers traveling uptown to a bank that would change it, then heading home, burning off a CD of the game and posting it to the customer – “I bought everything from Staples – who knows how much money I wasted.”

Without Wi-Fi in his apartment, Gilbert would go to a nearby café to work. “There's this one café I spent so much time in I gave them the physical copy of Blackwell when it came out,” Gilbert says. “I don't know if they ever played it.”

With the advent of PayPal, customers became more confident using their credit cards online. “I ended up getting most of my business those first few years through PayPal, and I actually got a PayPal debit card which I could use in shops and at events,” Gilbert recalls. “One advantage was when someone bought the game, I got the money right away. I didn't have to wait until Steam or GOG paid me. I still remember being at dinner with some friends, and for some reason, a lot of people bought The Shivah that day. On a whim, I said, 'This is on Rabbi Stone,' and I slapped my card down. It felt so good to actually pay for something with game sales.”

Gilbert released his first two games in just six months, but after launching The Blackwell Legacy on December 23rd and only seeing the sales trickle in, he says: “There was a big learning curve in terms of ‘How do I make this my living?’”

For the first half of 2007, instead of working on his follow-up to The Blackwell Legacy, Gilbert learned how to market and advertise his games. “Back then, there were so few indie games, but at the same time, no one was taking them seriously,” Gilbert says. He went looking for “anyone who showed a willingness to review or talk about indie games.” He found magazine and blog writers and creators on the newly launched YouTube who covered adventure games and pushed them toward The Shivah and The Blackwell Legacy while also letting them know he would have something new out that year.

By July, with money running short, Gilbert raced to develop a sequel to The Blackwell Legacy, releasing Blackwell Unbound just three months later in September. “I pulled it out of my butt,” Gilbert says. “And ironically, it's a fan favorite.”

The game is also a favorite for Gilbert. “It was just after my second game, I had a little bit of experience, a little bit of clout, a tiny bit of a name, but at the same time, I didn't have a lot of experience getting in the way,” Gilbert says. “I wasn't second-guessing myself all the time.”

Is this marketable?

While Wadjet Eye was growing and he was sustaining himself with game sales, Gilbert was growing worried that his business was too fragile. “My games took a year to make, and by the time they came out, I was almost out of money,” he says. “If the game failed, I would be done. I didn't like those odds.”

Through 2008 and into 2009, Gilbert made Emerald City Confidential, the first game he made for a publisher. Playfirst had made its success selling to the casual market, and Gilbert saw first-hand how that could be worked into an adventure game. Emerald City’s puzzles weren’t as complex as traditional point-and-click games because casual players were more interested in the story and characters. And, like in the old LucasArts adventure games, you couldn’t die, lowering frustration for players who may be more tempted to walk away from a game they were failing.

At the same time, Gilbert was finding his own success on the casual portals, selling his adventure games on the Apple Store. “My first royalty check from them was more money than I had ever seen at that point,” Gilbert says. “I thought, ‘Okay, the casual market seems to be where things should go.’”

Between these two experiences, Gilbert realized, “If I could have other games being worked on at the same time, I could spread out the risk, take more time with my own stuff, and keep the Wadjet Eye name out there. Hubristically, I thought, ‘I know how to publish games. I will just do what PlayFirst does for me.’”

Gilbert’s first attempt at publishing a game didn’t go exactly to plan. Hoping to appeal to the casual market, he approached Erin Robinson Swink, the artist who worked with him on Blackwell Unbound. She had just released a freeware puzzle game, Nanobots, that Gilbert thought could be perfect for casual players: “Cute colorful sprites seemed to be what was really popular.”

That lived-in experience is something you can't really fake [and] sincerity is a huge part of creating anything

David Gilbert

Gilbert had planned to make his own games as he published other developers’, but as Robinson Swink wasn’t a programmer, he took on that side of Puzzle Bots’ development. “I was paying for the privilege of working [on Puzzle Bots], and I wasn’t working on Blackwell,” Gilbert says. But the real problem came at release, Gilbert says. “The trends changed. It wasn't cute sprite art anymore. It was now spooky, realistic, hidden object games.”

The game sold, but nothing like what Gilbert had hoped. In the meantime, he had been making changes to Unbound’s sequel, Blackwell Convergence, that he thought would appeal to a more casual audience: “I was thinking, ‘Is this marketable?’” Looking back, it’s the game Gilbert “likes the least” in the series. “After that,” he says, “I just focused on what I liked.”

The lesson is echoed later in our conversation when I ask why all of his games are set in the same city. “I live in New York, I know New York, I love New York,” Gilbert says. “That lived-in experience is something you can't really fake [and] sincerity is a huge part of creating anything. You have to like what you're doing. If you're phoning it in, people can tell.”

Despite the missteps with Puzzle Bots and Blackwell Convergence, Wadjet Eye Games was now an adventure games publisher and the right people knew it.

Keeping the lights on

In 2010, Josh Nuernberger, a UX designer who had worked with NASA JPL to make interfaces for robots and an app to control drones for the Navy SEALS, contacted Gilbert. He had made a point-and-click game he wanted Wadjet Eye to publish

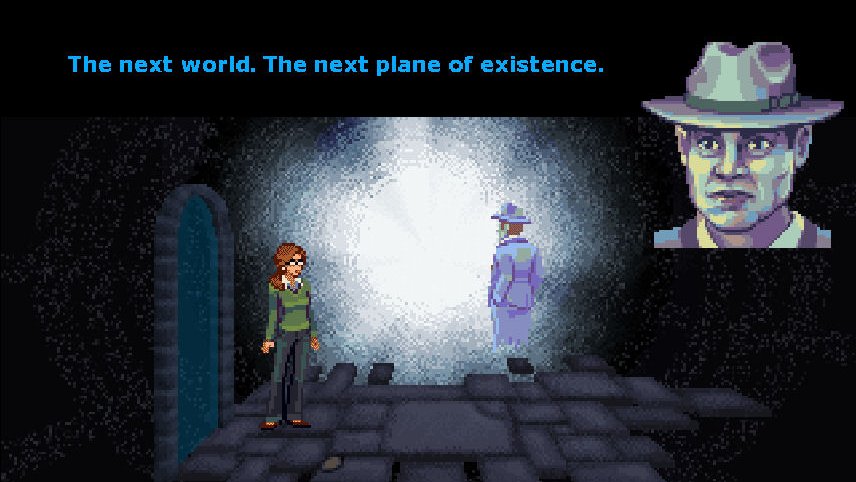

“My wife, Janet, and I played it,” Gilbert says. “We were on the edge of our seats for the entire thing. There was just nothing like it at the time.” Nuernberger’s game, Gemini Rue, has you play as two characters, an ex-assassin-turned-cop searching for his brother and Delta-Six, an amnesiac trapped in a mysterious rehabilitation facility on the outer reaches of space.

The game was almost complete; Neurnberger “basically wanted to finish it and not think about it anymore,” Gilbert says. As the publisher, Gilbert sourced QA, found voice actors, and handled sales and marketing, but he was able to stay out of the development and focus on his own game, The Blackwell Deception.

The sci-fi adventure was an instant success. “Gemini Rue sold more within its first week than everything Wadjet Eye had done by that point,” Gilbert says. “It was a phenomenon. It was the first game to go beyond the adventure game bubble.” Major sites like Rock, Paper, Shotgun and Giant Bomb were covering it, and it won PC Gamer’s Adventure Game of the Year 2011 award.

Gemini Rue was released in February 2011, and in October, Gilbert was able to launch his new Blackwell game. The model he originally envisioned while working on Emerald City Confidential, of publishing one game while developing another, worked.

Since then, Gilbert's has continued to both develop and publish games. “It works for me because when I reach the end of my own thing,” he says, “I'm about to have a nervous breakdown. The idea of starting over with another project is overwhelming, so being able to help someone else for a while appeals, but then I work on those projects for a few years, and I get all prima donna. 'Ugh, what about my vision, dammit?' I want to do my thing again.”

All I want to do

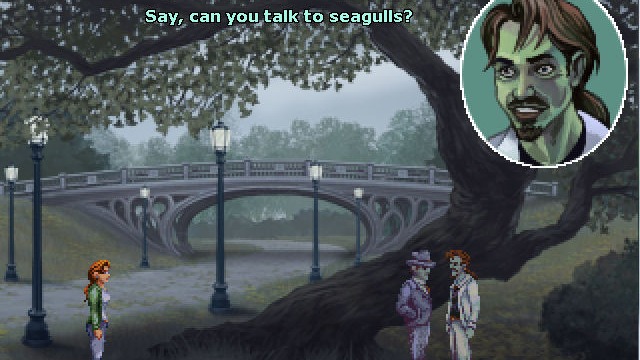

Gilbert is currently working on his next game, Old Skies, where you play a time-traveling tour guide, taking people to points throughout two centuries of New York history. It's larger than his previous work, with some chapters longer than his older games, but the production is still deliberately small – the largest team he has managed was just four people strong.

“Just managing four people was stressful,” Gilbert says when I ask what he would do with a larger budget for a larger project. “I can't imagine managing individual teams of people. I would have to rethink how I do everything.”

“If I got several million dollars to make a game, the fear is that now I gotta make a game that will earn that back,” Gilbert continues. “If I made one of my games with higher production values, I don't know if it would earn significantly more than I do now. There's a plateau for what these games can earn. At least, I don't think it would earn a several-million-dollar budget back.”

That’s not to say he doesn’t look at other game developers' work and wonder. “When a game like Baldur's Gate 3 comes out, and it's this phenomenon, I have this wistful feeling, 'It would be so nice to be part of something so big',” Gilbert says, “Then I think, ‘No one will know me, they'll just know the game.’ Being a small part of a big project doesn't sound very rewarding, but being a big part of little projects...”

This makes me look back at the headlines of the last month, the thousands of layoffs in January alone. Gilbert’s games have won awards and made him a living for nearly two decades. The way he works is sustainable in a way other larger studios are not. Since we spoke, he has acknowledged on X (formally known as Twitter) that the studios and publishers that chase growth have created jobs in the industry for people who wouldn’t have gotten into making games otherwise. But, while this terrible stint of news has continued, I’ve returned to something he told me repeatedly:

“I love doing what I'm doing. I love this. And my worry is that I will have to stop one day; that's always my fear that I'll screw up somehow, and I will have to have to stop. If I were given that kind of money, I would be able to make these types of games forever. And that's all I want to do.”

If you're looking to check out some more smaller games take a look at our best indie games list as well as the best roguelike games.