For most of her life, she was known as Lisa Qin, even though her birth name was Qin Qin (pronounced "Chin Chin"), the daughter of Chinese migrants.

As soon as she started school in Canberra, she changed her name to Lisa.

"Lisa was the acceptable, easy-to-pronounce name," she said.

Now, decades later and after throwing off the shackles of expectations, of who or what she should be, she's reclaiming her identity.

"And now Qin Qin is who I am," she said.

Qin Qin, a 38-year-old now living in Lawson with her husband James Gutteridge and their golden retriever Oprah, has been on a journey. Oh, what a journey.

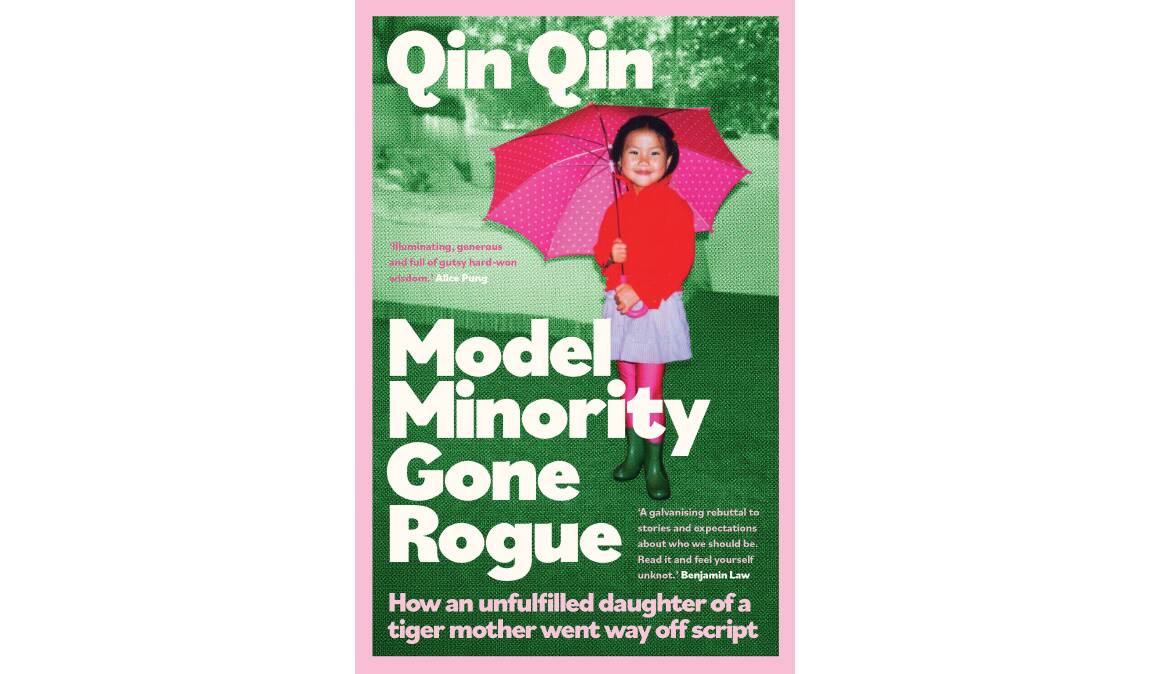

Her first book - Model Minority Gone Rogue - is being published by Hachette and will be launched in Canberra on Tuesday at the National Library of Australia.

It's her story of being a first-generation Chinese Australian. The model daughter, model student, model minority. Until she wasn't. Until she decided to live life on her own terms. Ditch the career in a commercial law firm in Sydney and go find out who she really was. Seek out her voice and use it.

"Model Minority Gone Rogue is my story of how I went off-script," she said.

"I was a corporate lawyer in Sydney and I realised, 'What am I doing with my life'?

"I was sitting at my desk and I watched out the window at the window washers and envied them. So something had to change."

In the book, Qin Qin unpacks how she internalised the "model minority stereotype", which emerged to describe Asian migrants' societal success. High-achieving. Law-abiding. Don't rock the boat. Be grateful. Career is everything.

"We have to be obedient migrants who stay quiet, keep our heads down, work hard and achieve. If we fail to do so, it's our fault," she said.

Model Minority Gone Rogue is one of the first titles to come out of Hachette's publishing partnership with broadcaster Benjamin Law.

Qin Qin had approached him about telling her story as a podcast, not realising he had also taken on this new role as a literary scout for Hachette.

"He told me to do what was 'closest to achievable', and for me writing was something I'd always wanted to do. He encouraged me to submit a proposal for a memoir rather than focus on a podcast," she said.

The idea for the book started to stir during COVID, when people talked about the "Wuhan flu" and Asian grandmothers "were being sucker-punched" because the world blamed Asians for the pandemic.

"When COVID hit, I realised, 'What is the cost of not speaking out'? The cost is vitriol, that anti-Asian vitriol and I needed to reclaim my story and my voice," she said.

Model Minority Gone Rogue is sassy, sad, funny, unvarnished. It's about the Asian experience but it's also universal. About a young woman grappling with life, whether that's career, travel, relationships.

"It's not just Asians who feel that pressure. It's migrants. Women. Girls. We feel like we have to be 'good'," she said.

Qin Qin was born in South-West China. Her father Ting Kui Qin was offered and accepted a place at the Australian National University and moved to Canberra in 1987 to complete his masters and then doctorate in the entomology, the study of insects.

In 1989, in the wake of the Tiananmen Square massacre, then-prime minister Bob Hawke offered asylum to Chinese students, including her dad. After graduation, he worked at the CSIRO

Qin Qin and her mother Ping Hua He moved to Canberra in 1989, initially living with her dad in his dorm room at Bruce Hall.

Qin Qin - aka Lisa - went to Turner Primary, Telopea High and Narrabundah College. She was the kid who loved stories and libraries but had to do maths and piano lessons after school. She was the high distinction student. Her mother, a university lecturer in China who cleaned houses in Canberra, wanted only the best for her daughter and her son.

In the book, Qin Qin writes about having one other Asian friend who had similar parents who were "overprotective and fanatical about ensuring our future academic success".

"Asian immigrant culture expresses itself through two primary vehicles (apart from Honda and Toyota): education for upward mobility and a strong work ethic," she writes in the book.

But, as she notes wryly, Canberra 30 years ago was a different place. She felt alone.

"In Canberra, back in the early 90s, there were so few Chinese people that if you saw one on the street, you'd go over, say hello and ask them to be your child's godparent," she writes in the book.

Qin Qin dreamed of being a foreign correspondent. She thought about doing Asian studies at university. She ended up doing commerce and law at ANU. Ended up working at a commercial law firm where going home at 10 every night was the norm. Where people hated their jobs but were too scared to change.

"One of my colleagues would say, 'Every time I walk into the building, I can smell the stench of decaying dreams'," Qin Qin said, with a laugh.

Something had to give. And it did. Qin Qin found out about the Teach for Australia program which fast-tracked high-achievers into teaching positions.

"It sounded crazy but I applied and I got in and I became a high school teacher in a disadvantaged school near Geelong," she said.

She loved it.

"No one was pretending to be someone they weren't, unlike in corporate law, where I had to hide all but 10 per cent of my personality," she writes in the book.

It was the start of her journey but it shocked people.

"They couldn't understand. It wasn't just my parents, it was my friends, too. 'You spent seven years studying to be a lawyer, why would you waste that'?" she remembered.

"Nothing is ever wasted, nothing is ever wasted."

Over the years, Qin Qin has still achieved. She's got a degree from Harvard. Worked for UNICEF. Been named as one of Australia's most influential young Asians. But she followed a path that was fulfilling, not necessarily prestigious or high-paying. Success came to her on her terms.

"It's listening to that quiet voice within that gets louder and louder if I ignore it. Every time I've listened to that voice, even though it's hard, there's a freedom that comes from that," she said.

Qin Qin now works at the National Library in Canberra as the coordinator of its Asian collection.

"In terms of now owning a peaceful, quiet life - I don't have to chase the external validation anymore. And through my story, you find out how that happens. It's messy but hopefully it's relatable, as well, to people feeling unfulfilled," she said.

Everyone is getting used to Qin Qin, including her husband James, who met her as Lisa.

"It's been a shift. I've gone by Lisa for decades. I changed it when I went to school because it was easier to pronounce and made me fit in more," she said.

"The reaction has been generally pretty good. There's more acceptance now. It's different from growing up in Canberra in the '90s as an Asian person. There's a lot more acceptance, curiosity, understanding

"It comes back to, 'I am worthy of my own name' and even if that takes a bit more time to try understand or pronounce, that's OK."

- Model Minority Gone Rogue is published on Wednesday by Hachette Australia. The Canberra launch is at the National Library at 5pm on Tuesday. Tickets are from trybooking.com.