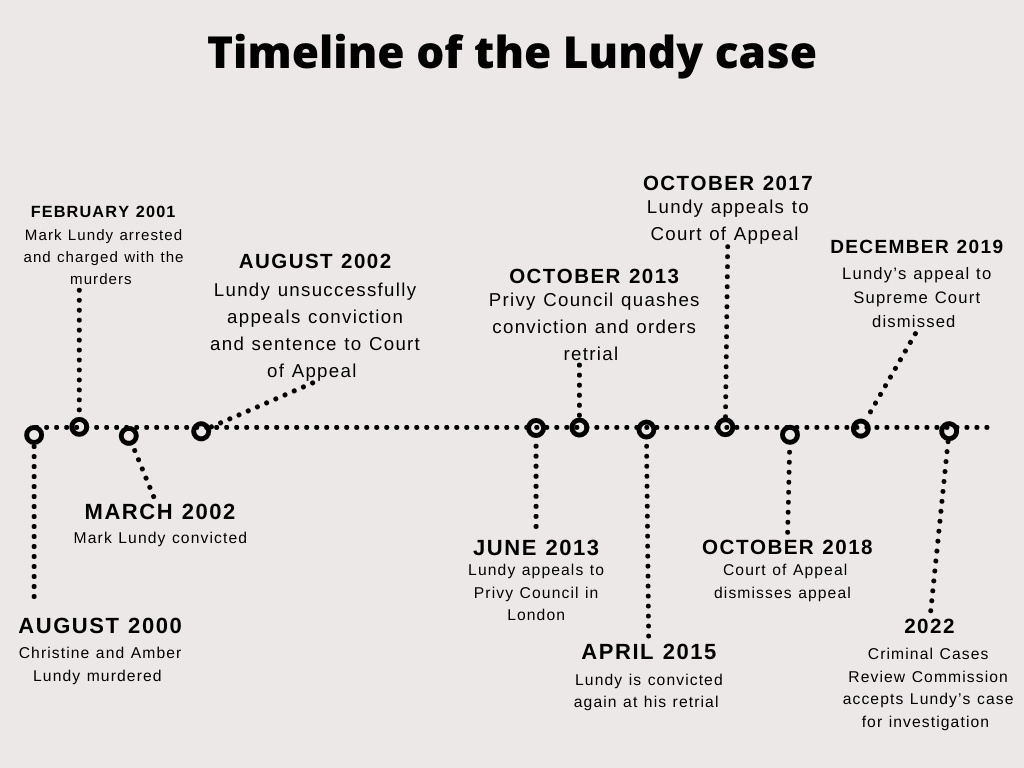

The whole nation was transfixed by scenes of big, tall Mark Lundy being held up as he broke down at the funeral of his wife and child, only to be jailed for their murder less than two years later. Twenty years on, following two unsuccessful Court of Appeal bids, a successful Privy Council appeal, a retrial that saw Lundy convicted again, and a failed Supreme Court hearing, it is a case that is not going away.

Digestion. Brain tissue. Wine. Cellphone tower. Petrol. Life insurance. Timing. Computer. A psychic.

This banquet of nine key elements is the moveable feast presented, altered and re-presented by the Crown in its arguments in one of this country’s longest running and most sensational criminal cases.

Mark Lundy was first convicted and imprisoned for the murder of his wife, Christine, and seven-year-old daughter Amber in March 2002, more than two years after they were found bludgeoned to death in their suburban Palmerston North home on August 30, 2000.

They had died from severe brain trauma, left by a small axe or tomahawk that has never been found.

Lundy has always maintained his innocence.

What followed has been more than two decades of failed attempts by Lundy’s defence team to exonerate him, mounting counter arguments to those put forward by the Crown, some aspects of which have been described by experts who have looked at the case as “beyond reality” and “little short of ludicrous”.

All along Lundy says he has been honest about his whereabouts on that August night when he was in Petone on a business trip for the sink company he ran with his wife.

Lundy said he drove to the nearby foreshore that evening and read his book, before returning to his motel where he drank half a bottle of rum. At 11.30 pm he called an escort agency, something he had done before on other trips, and spent an hour in his motel room with a prostitute.

But that’s not what the Crown said happened at the first trial. It alleged Lundy drove from Petone to Palmerston North where he murdered Christine and Amber sometime between 7pm and 7.15pm, before making the return trip to his motel - all within a three-hour window.

This meant he had to have driven the 300 kilometre round trip to Palmerston North at an average speed of 120km an hour.

Sometime just after seven

The night of August 29 had begun with Christine and Amber calling Mark Lundy in Petone at around 5.30pm, before ordering a meal from McDonald's at just before 5.45pm.

Later reports from the pathologist used by the Crown in the first trial suggested the two had died not long after their meal - at some time just after 7pm. This was based on their full stomachs and undigested food.

But with cellphone evidence pegging Lundy back in Petone at 8.29pm, the Crown was moved to prove he was able to cross the lower North Island during rush hour, kill his family, dispose of the murder weapon and clean himself up, before driving back to Petone, all while taking into account traffic lights, speed limits and potential traffic cops.

The psychic

Only one person claims to have seen Lundy during the three-hour window in which the Crown alleged he made his mighty dash.

That person was Margaret Dance, a self-described psychic who says she saw a fat man wearing a blond curly wig rushing away from the area at around 7.15pm that night.

On the stand, Dance denied her psychic powers would get in the way of her giving credible evidence, saying she was able to turn them off so she could remain completely factual in her remembrances.

What else did Lundy have to do in that short window of time to prove the Crown’s case? Manipulate the home computer, which evidence showed had been turned off at 10.52pm.

The Crown said Lundy had tampered with the computer to make it look as if it turned off at this time, something a forensic expert and former police intelligence officer would later describe as “so far-fetched and beyond reality it can’t be comprehended”.

The Texan pathologist

One of the most contentious issues was the organic matter found on Lundy’s shirt. In 2001 there was a pathologist named Rodney Miller visiting from Texas. He had never been on a crime scene or dealt with a criminal trial, nor received forensic qualifications aside from a three-month course almost 20 years prior.

He was approached by the police, who wanted him to confirm that the organic matter on the shirt was brain matter.

Miller was quoted as being amenable to police requests, saying “it would be great to nail the bad guy”.

Miller employed a technique commonly used to identify different diseases in laboratories called immunohistochemistry, or IHC.

It’s a technique well-documented in its usefulness at identifying different diseases, but not known for its ability to determine what part of a body any given sample comes from.

Nevertheless, Miller told the court that the stuff on Lundy’s shirt came from brain or central nervous system tissue.

It’s a test that hasn’t been used this way in criminal trials elsewhere in the world.

(Eventually - after the trial - the Court of Appeal were to agree with the defence submissions that this evidence should not have been included in the trial.)

The money

Another part of the Crown’s case rested on the state of Lundy’s bank account.

He and his wife ran a kitchenware business together. Mark went out on the road doing the sales, while Christine handled the administrative and accounting functions.

Together they had a business that had its head above the water, and were handling their mortgage and looking to expand into the wine business.

The couple had received a good amount of advice on how to best get into wine.

A Palmerston North businessman, whose name is suppressed and is known as Mr M, spoke to the Court about the Lundy’s vintner ambitions.

The Crown theory at trial was that Lundy murdered his wife and child to solve his financial issues and avoid declaring bankruptcy. It was not so straight forward and this theory was roundly challenged.

Evidence was given by Mr M who confirmed he offered to cover all costs that Lundy had incurred which was $100,000 excluding the penalty interest on the land. So as far as Lundy was concerned those costs were covered.

Furthermore, Mr M also confirmed that he had spoken to Lundy about the penalty interest and advised that if they simply put the land back on the market that would recover the costs of the penalty interest and the original purchase price. Therefore, the land could simply be sold avoiding any penalty interest.

The land was in fact sold following the murders for a profit. Lundy’s team said all of this evidence negates the Crown’s theory.

They also add there was no benefit financially to Lundy murdering Christine. Whilst the Crown pointed to a recent increase in both of their life insurances, it was agreed by the broker this was at his behest, and that the Lundys had not increased the amount as much as he had first suggested as they thought the repayments would be too great. In any event, the policies had not yet taken effect, and any benefit from that was greatly outweighed by the fact that in murdering Christine, Mark Lundy would not be able to run his sink business.

(In the first three months of the 2000 financial year the sink business went up in sales by 37 percent.)

The sink supplier got all the money owed and the receivers netted about $50,000 so there was money in the sink business.

Two counts of murder

The Crown was successful and Mark Lundy was convicted on two counts of murder. In August that same year he took the conviction to the Court of Appeal, but was unsuccessful.

He would be in prison for more than a decade before an appeal to the Privy Council in 2013, which saw his conviction quashed and a retrial ordered.

The Privy Council raised three main flaws with the Crown’s case, including questions over forensic testing methods used to analyse specks of tissue found on the polo shirt Lundy said he was wearing that night, which the Crown posited was brain matter from Christine. The second flaw was the plausibility of conducting the murders within the window of time proposed by the Crown.

The third issue was the scientific analysis of food digestion used to determine time of death, with the Privy Council stating: “Since the trial, a ‘welter of evidence’ from reputable consultants has cast doubt on the methods the Crown had relied on to establish the time of death based on the contents of the victims’ stomachs.”

Crown U-turn

Lundy spent almost two years out of prison before his retrial and second conviction in 2015.

The Crown made an almost complete U-turn, throwing out much of their evidential arguments that were used to convict Lundy in the first place.

Instead of talking about Lundy’s frantic drive from Petone to Palmerston North, they now contended he arrived at the family home sometime in the early hours of the morning to kill his wife and child.

The pathologist’s report about the partially digested McDonald's was not used in the Crown’s case this time, meaning it could expand the time window in which the murder occurred up to 14 hours - the time between Christine’s last phone call with a friend at just before 7pm and when her brother, Glenn Weggery, found their bodies the next morning.

The Crown also changed tack on the computer evidence. Instead of, as in the first case, claiming Lundy had manipulated the home computer to show a different shut down time, at the retrial the Crown said it hadn’t been tampered with after all.

The testimony from psychic Margaret Dance was also left out of the Crown’s second try at the case, as it pinned Lundy’s movements down to a specific time in the evening.

Instead, the Crown’s case at the second trial painted a very different picture – rather than speeding back to Palmerston North, Lundy would have driven carefully so as not to be seen.

The Crown now accepted Lundy’s earlier testimony that he had left the motel in the early evening to read a book by the seashore, but now they alleged this movement was so he could get his car out of the motel carpark without arousing suspicion when he made his middle-of-the-night moves later.

The first trial had hinged on a spattering of organic matter on a polo shirt found on the backseat of Lundy’s car by police. Lundy himself had volunteered this was the shirt he had been wearing on the night in question, and under the microscope it went.

Institute of Environmental Sciences and Research forensic scientist, Bjorn Sutherland, found two spots of some kind of organic matter on the shirt’s pocket, and another on the sleeve, which he tested and concluded there was a significant likelihood they contained traces of Christine’s DNA.

Just before the retrial, the samples were tested once more and cow, pig and sheep DNA also showed up.

At the time of the first trial, a neuropathologist named Dr Heng Teoh had said the samples were in too poor a condition to form the basis for a conviction. These comments, however, were not passed over to the defence, and only came to public attention when they were released around the time of Lundy’s first conviction being quashed at the Privy Council.

The very same samples were then given to the FBI and UK Home Office for further examination, but both bodies reported that they would not be able to tell what kind of cells were present.

Unknown male DNA

Perhaps the biggest mystery in this saga is the forensic evidence that has never been solved.

Christine was found with 21 unknown strands of hair entwined in her hands, from an unknown male, which did not match to samples of Lundy’s own hair. DNA was also found under the fingernails of both Christine and Amber, which remains unidentified.

Fingerprints, palm prints and footprints around the scene were also not matched to Lundy, with police unsure to this day as to who left them.

Lundy’s next appeal was in 2017, which took more than a year to be dismissed by the Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court.

Te Kāhui Tātari Ture or the Criminal Cases Review Commission is investigating an application for a review of the case, after which it will make a call on whether to refer the case back to the Court of Appeal or not.