In defending a Federal Court case brought by opponents of her decisions to approve two export coal mines, Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek is relying in part on what critics call the “drug dealer’s defence”.

It’s reasoning that argues: if we don’t sell this product, someone else will.

Prime Minister Albanese has argued the same thing, telling The Australian

policies that would just result in a replacement of Australian resources with resources that are less clean from other countries would lead to an increase in global emissions, not a decrease.

Albanese’s reasoning is that saying no to new Australian coal mines wouldn’t cut global emissions, it would just produce “less economic activity in Australia”.

If it sounds like a familiar argument, it is – past prime ministers and the coal industry have made similar claims for decades.

It’s possible to test this argument using economics, putting to one side the question of whether it is morally justifiable.

The defence works for drug dealers

Let’s look at how this defence works with retail drug dealers, many of whom are drug users themselves.

Street-level drug dealing is a job that doesn’t require much skill and pays above the minimum wage, even after allowing for the risk of arrest.

As a result, as soon as one dealer is arrested, someone will enter the market to replace the dealer. For this reason, drug policy has shifted away from traditional modes of street-level enforcement and towards community partnerships.

But coal is different. Global markets are supplied by a range of producers, each with different costs. Some mines can cover their costs even when world prices are low, others require very high world coal prices to break even.

In the case of metallurgical (coking) coal used to make steel, Australia’s mines are mostly at the low-cost end of the spectrum as shown below:

Indicative hard coking coal supply curve by mine, 2019

Thermal coal, used in electricity generation, is more complex, since much of the variation in price relates to its quality, rather than extraction cost.

Nevertheless, the fact remains that if one producer withdraws from the market or reduces output, it is highly unlikely to be replaced by an identical-cost producer.

It is likely instead to be replaced by a higher-cost supplier who needs a higher price to cover its costs. That’ll make the coal less attractive to the buyer who would have bought from the low-cost producer, making that buyer likely to buy less of it.

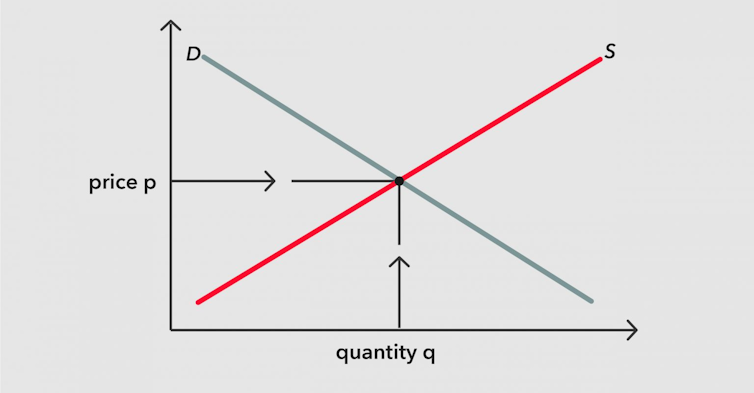

This is Economics 101, illustrated in the supply and demand diagrams in just about every economics textbook.

Why Australia’s coal matters globally

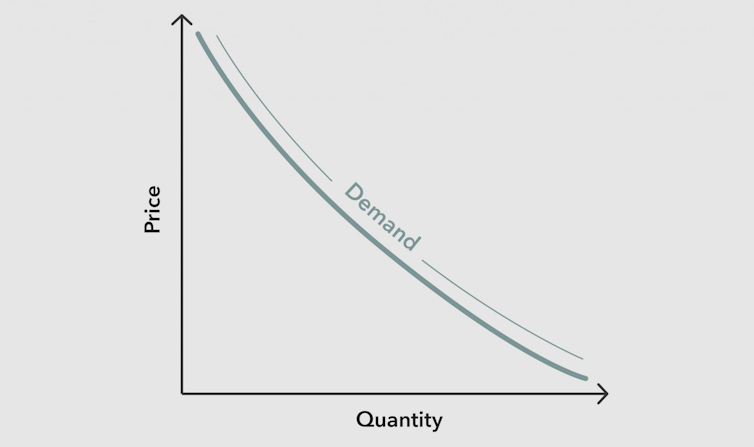

In most markets, the demand curve is downward sloping, meaning the higher the price, the less the buyer wants.

And in most markets, the supply curve is upward sloping, meaning the higher the price, the more the seller is prepared to sell.

What’s bought, and for how much, depends on where those curves meet.

If the supply curve moves up, because the cost of supply has increased, the price at which the good is bought will move up and the quantity bought will move down.

In the figure below, the supply curve S1 is the current global supply.

If Australia supplies less coal, the supply curve will shift from S1 to S2, resulting in the higher price P2.

The higher price will result in increased supply from competitors, but also a reduction in the total amount consumed, a cut from Q1 to Q2.

This means that, contrary to government claims, our decisions will have an impact on global emissions and ultimately on global heating

Moreover, Australian decisions aren’t isolated.

All around the world, governments, financial institutions and civil society groups are grappling with the need to transition away from coal.

Proposals for new and expanded coal mines and coal-fired power stations face resistance at every step. In particular, the great majority of global banks and insurance companies now refuse to finance and insure new coal.

This means that the long-run response to a reduction in Australia’s supply of coal will involve less substitution and more of a drop in use than might be thought.

For coal, the drug dealer’s defence is shoddy

It makes the drug dealers defence for exporting coal especially shoddy.

It would be open to Plibersek to make another argument: that in the government’s political judgement, Australians are not willing to wear the short-run costs of a transition from coal, regardless of the impact on the global climate manifested every day in bushfires, floods and environmental destruction.

But instead, we are being told that if Australia cuts supply, other suppliers will rush in, without being told about their costs and what will happen next.

In markets like coal, with a fixed number of suppliers facing different costs, demand responds to the withdrawal of supply in the way the economics textbooks say it should.

John Quiggin is a former Member of the Climate Change Authority.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.