SCOTS have long been known as a martial race, with a reputation that cuts both ways. On the one hand the soldier has been feared for his ferocity and, on the other, admired for his generosity.

An example is a man who stands at the roots of the Jacobite movement, born about 1650 as plain John Graham, who came from a landed family of Claverhouse in Angus.

By Sir Walter Scott he was nicknamed Bonnie Dundee, recalling that his toughness was all the same softened by an almost feminine beauty. To his many enemies he was Bluidy Clavers, one of the most savage figures in an age marred by incessant war.

It would be going too far to think of Claverhouse as the common type of boneheaded military gentleman. He got a degree at St Andrews University but straight afterwards left to make his military fortune as a mercenary in Europe. There he met and befriended another cold warrior, William of Orange, and through him a later father-in-law, James, Duke of York, the younger brother of King Charles II.

By the time Claverhouse returned home, there was plenty of work for him in Scotland, especially in suppressing the Covenanters. These were for the most part simple country folk who believed religion should conform to the beliefs of the people rather than be controlled by princes and priests.

Despite the restoration of the House of Stewart, they wanted a Presbyterian Kirk. When they were not allowed to have one, they worshipped at services held in the open country.

Claverhouse was an uncompromising supporter of the governments trying to put a stop to all this. In 1678, Charles II made the Duke of York a sort of viceroy in Scotland, permanently resident at the Palace of Holyroodhouse.

He led the suppression of religious dissenters and gave Claverhouse a central role in the rustic operations. Claverhouse gained a reputation for cruelty which won him political influence, as a soldier who could win victories for the royalist government where others could not.

Even so, this method of ruling Scotland could not be counted a success and by 1688 it was a country ready for revolution. King James VII had succeeded his brother Charles three years before and had done everything possible to prepare for the official toleration of a Catholic minority.

To Presbyterians this was merely the prelude of an effort to convert them all back to Rome, if necessary by force.

In November 1688 the mob took over the streets of Edinburgh, sacked the royal palace and burned down the medieval abbey next to it. The king’s ministers hid or fled.

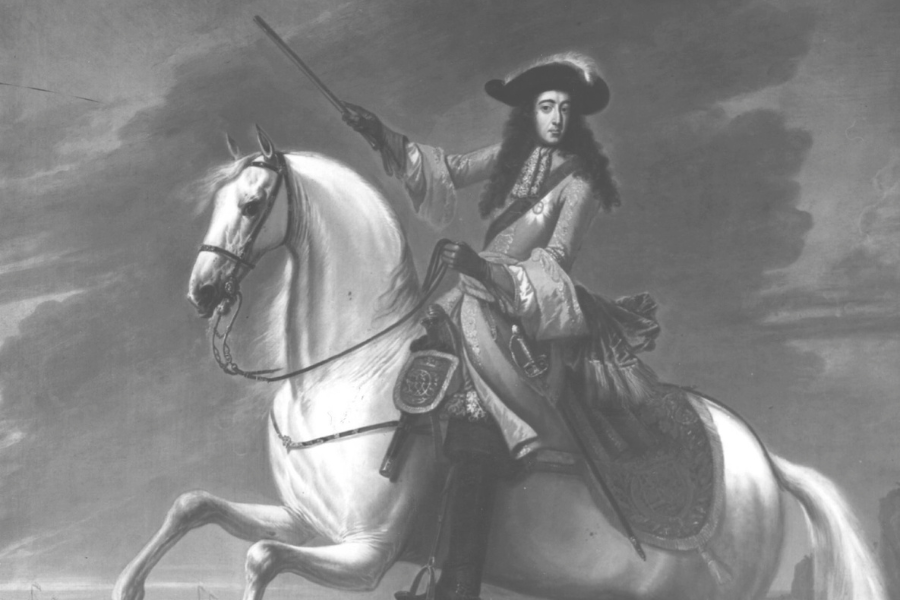

James VII looked to Claverhouse as one of the few loyal and able men on his side. He made the uncompromising soldier Viscount of Dundee and Lord Graham of Claverhouse. In addition to his military duties, Claverhouse was now entitled to attend the convention which was called for in the spring of 1689 to chart a way forward in this Glorious Revolution.

As soon as the convention met it was clear there would be little chance of it restoring the legitimate line of Stewarts. Apart from anything else it had a majority of Presbyterians who would take over the Church of Scotland once again, and it adopted the principle, completely new to Scotland, that the Scottish monarchy was responsible to Parliament.

Claverhouse and a minority of royalists soon decided they had had enough. The viscount consulted the Duke of Gordon, governor of Edinburgh Castle, and rode for the north. He headed for Dundee Law and there raised the old king’s standard to signify that, for him and his friends, there was to be no change of regime.

He rode down the Tay to threaten the city of Dundee (though he did not try to take it). Then he turned into the mountains to set about the task of rallying the Highland clans.

Scotland was therefore in turmoil, and this was not something the governments either in Edinburgh or in London could afford to ignore. William of Orange was about to be crowned king of the three British kingdoms, with his wife Mary, a daughter of the Stewarts, as his consort. William won the Battle of the Boyne and conquered Ireland. It would be Scotland’s turn next.

These were days, however, when Scotland had to be secured by Scotsmen. The Highlands remained largely under the control of clans loyal to the Stewarts with Claverhouse as their commander. He might not appeal to the Lowland population, but they were not protected by any regular forces capable of the task.

Forces had to be rushed from elsewhere and they were placed under the command of a Scottish general recalled from Europe, Hector Munro of Scourie. He landed at Leith and set about organising an army as best he could. He could count on organised units of Covenanters from the southern counties.

They were not regular soldiers but their absolute commitment to the Protestant cause and consequent discipline on any battlefield where they might be placed made them just as good.

The advance guard of Munro’s army began its operations in the north by advancing there along the shortest route, which led through the Pass of Killiecrankie. The road before them was empty and the summer weather glorious.

The royal army did not know that behind the visible contours of the hills Claverhouse’s army was waiting.

It held still until the hot afternoon had tired the soldiers somewhat and brought them to the narrowest part of the pass.

Then Claverhouse gave the order for the Highland charge, a so-far undefeated manoeuvre that owed its invariable success to its terrifying nature.

The clansmen came at a bound down the slopes screaming their battle cries and slashing with their broadswords at everything in their way. All their enemies could do was run. And usually they were slaughtered anyway as they turned and fled. Killiecrankie was soon a pass full of corpses. Only the Covenanters starting their climb at the bottom held their ground.

With this triumph certain, Claverhouse sought a little height where he could get a view over the scene. With his closest officers he rode up an eminence partly obscured by smoke from the fighting. Nobody could see quite what was happening. But when the smoke blew onwards, the corpse of Claverhouse lay on the ground. An ugly wound marked the oxter that had been penetrated by a bullet.

The greatest victory of this gallant and fearless general had been marked by his own death. The Jacobites had won, yet they had lost, since they never again attained the military superiority that Claverhouse would have given them if the war had continued. He was brilliant and inspiring enough to set the Jacobite bandwagon on the road, yet without him it was doomed to failure.