An Islamic State-linked group in Uganda attacked a school in June, killing more than 40 people, mostly students, in what seems to be an escalating trend of terrorism against schools. The attackers set fire to school dormitories and used machetes to kill and maim students.

This was the latest in a cycle of shocking attacks on schools around the world. The Nigerian group Boko Haram infamously kidnapped more than 200 girls from a school in 2014, and it has attacked other schools throughout the country.

Many more attacks have occurred since then. In Afghanistan, IS affiliate IS-K has repeatedly bombed educational institutions in recent years, often killing dozens of children or teens. In 2020 in Cameroon, sources suggest that separatists fighting for their own, independent state attacked a bilingual school, killing eight children.

Why would a group carry out such an attack, killing schoolchildren? These attacks are happening more frequently in recent years, and they also tend to be carried out by particular types of groups.

I recently co-wrote a book, Insurgent Terrorism: Intergroup Relations and the Killing of Civilians, with political scientists Victor Asal and R. Karl Rethemeyer, examining the use of terrorism (intentional civilian targeting) by rebel organisations in civil wars. We dedicated a chapter to understanding attacks on schools and discovered a few patterns.

First, attacks on schools are on the rise. In the years examined in our book, 1998-2012, we found a marked increase starting in the late 2000s during civil wars. In the 1990s and early 2000s, there fewer than 20 attacks per year on schools by rebel organisations. But between 2009 and 2012, there were more than 90 such attacks per year.

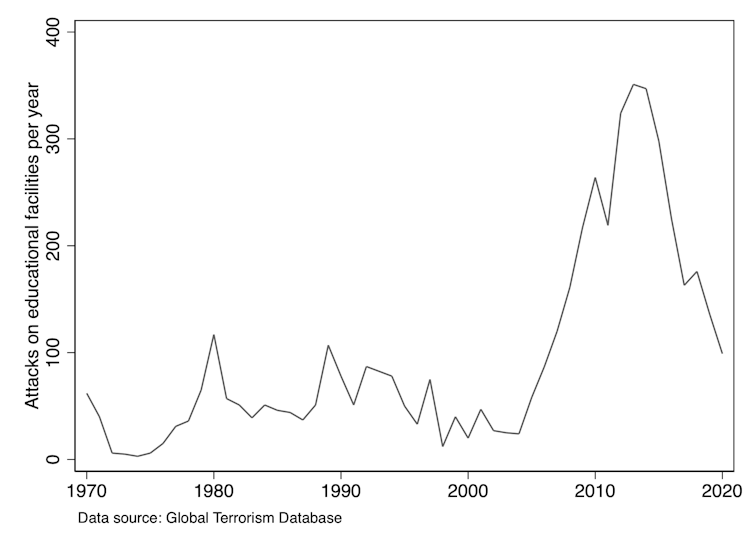

Examining more recent data on terrorism generally, and not only during civil wars, we see a similar increase starting in the late 2000s. The graphic below shows a massive increase in terrorist attacks on schools.

Terrorist attacks on schools, 1970-2020

The annual average number of terrorist attacks on schools in the 1980s and 1990s, according to the Global Terrorism Database, was less than 60. In the 2000s, the average year saw nearly 80 school attacks. In the 2010s, there was an average of 250 terrorist attacks on schools per year. After the early 2010s peak, the number of attacks started to decrease, but numbers are still far above what they were in the 1990s or early 2000s.

The increase in terrorism against schools is in part because influential global networks such as al-Qaida and IS seem to encourage it, but also because groups learn from others that this is a good way to bring attention to their cause, to force a government to give in, or to intimidate a rival community.

Read more: Nigeria's new national security bosses: 5 burning issues they need to focus on

A second pattern we noticed was that the organisations that carry out these kinds of attacks tend to have a few attributes in common. Groups that attack schools tend to be in alliances with other rebel or terrorist organisations. These alliances provide extra resources to groups, which are essential for large-scale attacks. For example, allies might provide explosives, vehicles or recruits. Cooperative relationships with other rebels can also contribute to heinous attacks because groups learn tactics from each other, and they might pressure each other to use extreme tactics.

This seems to be the case with the group behind the recent Uganda attack, the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF). It has been cooperating with IS since 2017 and has received funding from it. The funds and propaganda support seem to have enabled ADF to carry out increasingly vicious attacks. Additionally, other IS-affiliated groups have attacked schools, so it is possible that the main IS encourages this, or that the groups are learning from each other.

We found that groups that had recently been subjected to government crackdowns were more likely to subsequently target schools, while groups that had recently received government concessions didn’t attack schools the following year. This is consistent with other research finding that government repression of religious freedom seems to lead to terrorist attacks on school.

The Uganda school attack, where boys and girls were killed and buildings set alight with people inside, was apparently intended to send a message to the government and its president Yoweri Museveni. Victims reported that the attackers said: “We have succeeded in destabilising Museveni’s country.”

Interestingly, in our research, we did not find that religiously oriented groups, such as Islamist groups, were more likely than other types of groups to attack schools. Certainly, some Islamist groups have carried out these attacks – such as the recent Uganda school killings.

IS-K’s attacks are intended to intimidate the mostly Shia Hazara minority community, consistent with IS-K’s extreme religious views. But non-religious groups, such as the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia and the Communist Party of India (Maoist), have also repeatedly attacked schools.

Overall, attacks on schools occur because militant organisations see that they bring a great deal of attention – including from international news media – to their cause. Terrorism is fundamentally violent propaganda, and groups that use terrorism constantly innovate, seeking new tactics to help them stand out. They also hope the increasingly extreme methods will pressure governments to give up.

It seems likely that terrorist attacks against schools are going to continue. Governments should prioritise safeguarding educational institutions, and the international community should work harder to prevent these kinds of attacks.

Brian J. Phillips does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.