The protests sweeping Texas cities are a stark reminder of the pain caused by police violence.

By Michael Barajas

June 5, 2020

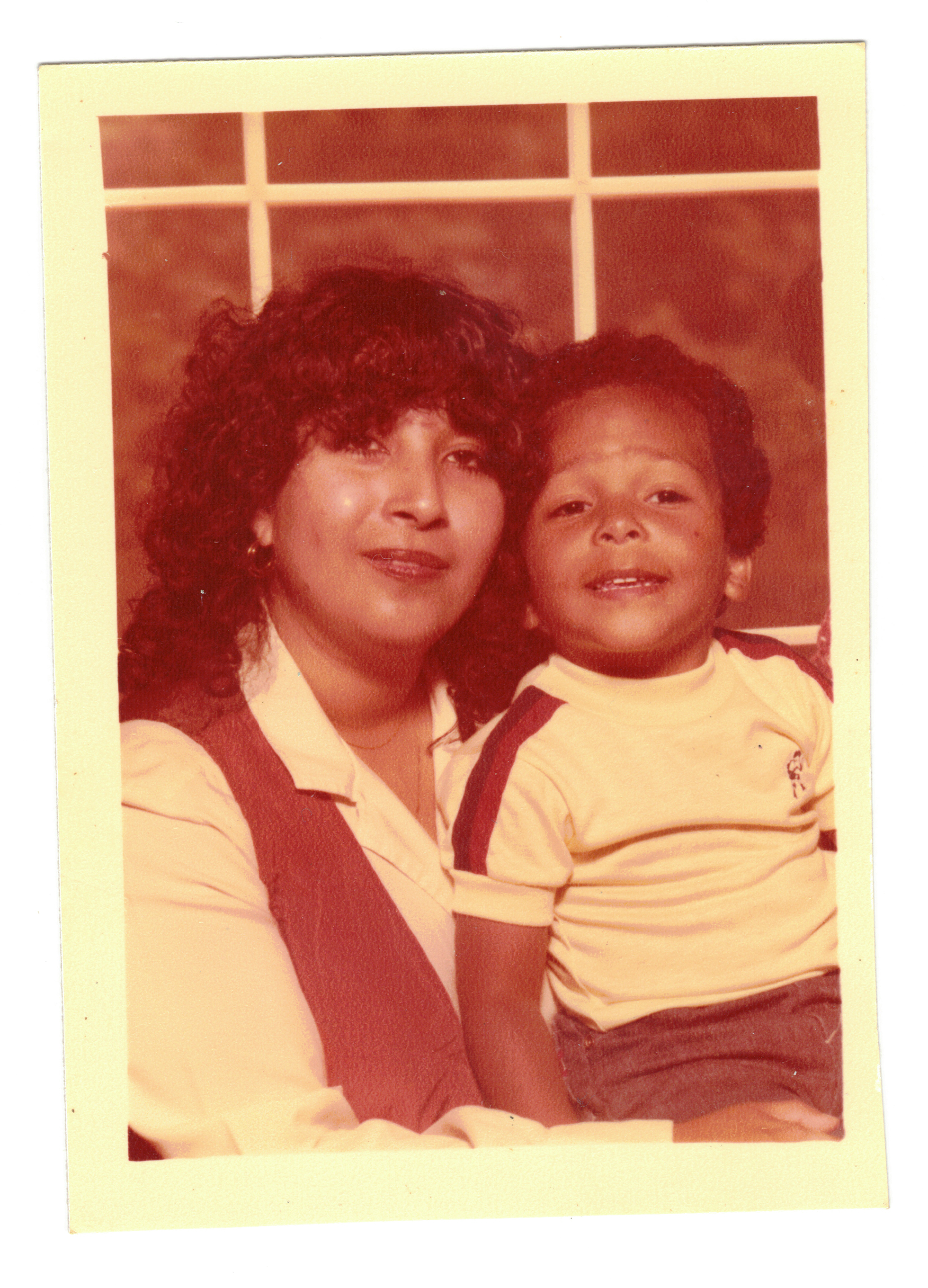

Red rose bushes grace the lawn outside the South Austin home where Mike Ramos lived with his mother, Brenda, for a decade. He planted them several years ago in memory of his grandmother. Brenda thinks of her son whenever she sees them, and when she walks down the agave-lined pathway he cleared for her leading to the backyard. But the lawn is overgrown now that her only son is no longer alive to tend to it.

“My baby did everything for me. He used to do the yard, and now look,” she says, pointing to the grass.

Earlier this year, on the evening of April 24, officers with the Austin Police Department (APD) were dispatched to the apartment complex where Mike Ramos, 42, had recently moved with his girlfriend. Someone had called 911 claiming they saw two people doing drugs in a car. According to a report filed with the Texas Attorney General’s Office late last month, as police closed in on Ramos, “an update to the call indicated the male subject had a gun.”

When officers arrived, they cornered Ramos and his girlfriend in the parking lot, blocking the exit to the complex and ordered them out of the car at gunpoint. Cell phone video recorded by a neighbor shows Ramos standing at the driver side door with his hands up, shouting that he was unarmed, before an officer fires a “less-lethal munition,” a so-called bean bag round, striking Ramos on his left side. In the video, Ramos then gets back into the car and pulls out of the parking spot as his girlfriend bails from the passenger side, narrowly escaping the volley of bullets fired by another officer as Ramos drives away from police, toward a dead end in the complex. Ramos was killed. Weeks after his death, police confirmed that he didn’t have a gun.

Ramos’ name has been shouted by thousands of marchers who have flooded the streets of Texas’ capital city in the enormous protests sparked by the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis. Ramos, who was Black and Latinx, was the latest unarmed person killed by police in Austin, a city that espouses progressive politics but has a long and ugly history of segregation and racist and brutal policing. Activists in the city have struggled for years to dismantle the systemic barriers to police accountability, such as amending a police union contract that shields cops accused of misconduct. In light of this weekends’ protests, many in Austin and across the country are calling for deeper, more fundamental changes, such as divesting funds from law enforcement to reinvest in other community services like health care, substance abuse treatment, and affordable housing.

Yet as police chiefs across Texas join the international calls of “Justice for George Floyd,” they have also largely avoided talking about the legacy of police brutality and killings that have fueled the protests in their own backyard. Austin-area police chiefs who condemned Floyd’s killing have declined to weigh in on Ramos’ death. Houston Police Chief Art Acevedo, who’s drawn national praise for his emotional response to Floyd’s killing, has clashed with protesters calling him a “fucking liar” and “hypocrite” over how he’s handled a recent spate of police shootings in his own city. “You walk for Minnesota, will you walk for what happens in Houston?” one angry protester shouted at Acevedo this week. Politicians alike have demanded justice for George Floyd, listing him alongside other nationally known victims of police brutality such as Eric Garner and Tamir Rice, while conspicuously ignoring the shootings of unarmed Black men that occurred in their own cities in recent years.

In Austin, and other major Texas cities, officials’ condemnation of Floyd’s death also stands in stark contrast to the violence their police forces have inflicted on protesters. On Monday, Austin Police Chief Brian Manley, who faced calls for his termination even before the recent demonstrations, confirmed that police injured several people by firing “less-lethal” rounds at crowds last weekend. The victims include a pregnant woman, a 16-year-old boy, and a 20-year-old college student who remains in critical condition and is expected to suffer serious brain damage. Police also fired on medics who tried to help injured protesters.

Several community groups are demanding the resignation of Dallas Police Chief Reneé Hall for deploying officers who fired tear gas, rubber projectiles, and pepper balls at protesters, leading to several reported injuries. In Houston, police fired pepper spray into crowds and corralled protesters into a cramped police substation, increasing their risk of contracting COVID-19. Cops in San Antonio have gassed protesters and fired rubber and wooden projectiles into crowds.

The violence against protesters in Austin, along with the killings that preceded the demonstrations, highlight the limits of police reform efforts in the city. Natasha Harper-Madison, the only Black member of Austin’s city council, began a meeting this week with an emotional plea to her colleagues, condemning the violence against demonstrators and urging her colleagues to push for systemic change. “This weekend we saw thousands of Austinites take to the streets in what were largely peaceful demonstrations against an absolutely broken system,” she said. “The deaths of people like George Floyd, Mike Ramos, and Breonna Taylor continue to highlight the racism embedded in our criminal justice system.”

As Harper-Madison continued, her voice shook with anger and sadness. “We cannot continue to stick our fingers in our ears and wait for the next eruption of anger. We have got to start to root out the racism in our police department. … The time for talk is absolutely over.”

The killing of Mike Ramos also appears to illustrate problems that are endemic to policing in Austin and other U.S. cities.

While training varies by jurisdiction, some experts who instruct cops across the country have been criticized in recent years for justifying almost any police shooting. The former director of Texas’ state police academy has rationalized shooting and killing a suspect with his hands raised.

Mitchell Pieper, who fired the “less than lethal” bean bag round at Ramos while his hands were in the air, was a rookie just three months out of a police academy that has been accused of promoting a violent “warrior” mentality. In 2018, ten former cadets sued the Austin police training academy, claiming instructors berated prospective officers who expressed a desire to help the public. They reportedly were taught that suspects who resist or fight deserve “a legal ass-whooping.” The cadets also claimed that instructors repeatedly demeaned homeless people and sex workers, calling them “cockroaches.” The trainers even allegedly encouraged cadets to target “transients” when bored to make an easy felony arrest.

National data on police shootings is notoriously deficient, however. A Texas Tribune analysis of five years worth of shootings in 36 police departments across the state found that people of color were more likely to be shot regardless of whether they were armed. In 2015 the Washington Post investigated and discovered that many officers who kill have previously been involved in fatal shootings. Officer Christopher Taylor, the 10-year APD veteran who fired the fatal shots at Ramos as he drove away from police, was already under investigation for his involvement in the shooting death of a college professor from Sri Lanka who was having a mental health crisis 10 months before—an uneasy reminder of APD’s terrible track record for responding to people with mental illness.

“He had just killed someone right before he took my son,” Brenda Ramos says. “That shows right there that they haven’t done anything to stop this from happening again.”

Ramos says officers questioned her mere hours after he was killed, leaving her feeling further traumatized by APD’s handling of the shooting. “It just wasn’t the right time, getting questioned right away like that,” she says. “I’d just found out, I was hurting so bad, it just wasn’t right.” Later, when Brenda started asking her own questions about the shooting, police told her to go through the public information office.

Her anguish was exacerbated by coverage of her son’s killing by local media. She says she wanted to wait several weeks to watch the video of the shooting, but it was unavoidable. “They were playing it on TV and I walked away, but I could still hear it. I just started crying because I could still hear my son’s voice,” she says. After pleading to see her son’s body, officials told her to bring a hat to cover the damage to his skull. A lifelong University of Texas football fan, Brenda brought his favorite Longhorns cap. “I almost didn’t see my son at all because they shot him up so bad,” she says between sobs. “Come on, that’s murder.”

Brenda waits to see whether Officer Christopher Taylor will face serious discipline or criminal charges—both of which are historically rare. She wants state legislators to pass a law requiring immediate sanctions for cops who kill unarmed people and provide protections for grieving families. For now, she visits her son’s gravesite every day, sometimes sprinkling holy water or orange rose petals. She also keeps a tub of Mike’s T-shirts at her home to give to his grieving friends who stop by. She says one of his best friends plans to frame one in his memory.

Read more from the Observer:

The Protests Against Police Brutality in Texas, in Photos: Demonstrations against police brutality are taking place in cities large and small across Texas.

‘Heroes’ No More: Grocers Are Already Clawing Back COVID-19 Worker Benefits: Kroger revoked its “Hero Pay” in May, while public health experts warn of COVID-19 surges as Texas reopens.

Why Is APD Responding to Mental Health Crises like Violent Crimes?: The police officer who shot Mike Ramos was involved in the death of neuroscientist Mauris DeSilva in July, which called into question law enforcement’s outsized role in mental health incidents.