The latest state-of-our-waters report shows why we really need Three Waters reform. It's partly because there are still some pretty grim numbers, but also because there are welcome signs the reforms we already have are starting to make a difference

Analysis: With all the political shenanigans around Three Waters it’s easy to forget the push to reform our water systems began with the Havelock North campylobacter contamination disaster in 2016. Four people died, 5000 got sick; the problems around our water quality got up-close and real.

It’s also easy to forget that merging 64 water providers into four water entities is just one part of a bigger Three Waters reform package triggered initially by Havelock North.

Taumata Arowai became New Zealand’s drinking water regulator in November 2021 and will take on responsibility for regulating quality in wastewater and stormwater networks in 2024.

READ MORE: * Our water problem in 15 worrying charts * Urgent need to change the narrative on Three Waters

Meanwhile, the Government is also setting up the Commerce Commission as an economic water regulator. Its job will be to make sure there’s the right level of water infrastructure investment, to enforce information disclosure, drive efficiency gains, and ensure consumers are protected.

This is important stuff, as Water NZ’s National Performance Review (NPR) report, published last week shows all too well.

As Newsroom has reported in the past, the NPR has tended to be an unappetising inventory of a water system in turmoil – a fifth of water wasted through leaks, persistent problems with contaminants in some places, consent breaches, long-running under-investment, and much more.

This year’s report still contains plenty of bad – and in some cases worsening – news. But as early reforms bite, and as the powers-that-be react to increasingly visible signs of failing infrastructure and the reality of further oversight looms, there are a few positive signs.

Lesley Smith, author of the National Performance Review and Water New Zealand’s insights and sustainability advisor, talked to Newsroom’s business editor Nikki Mandow about what the report tells us about the need for water reform.

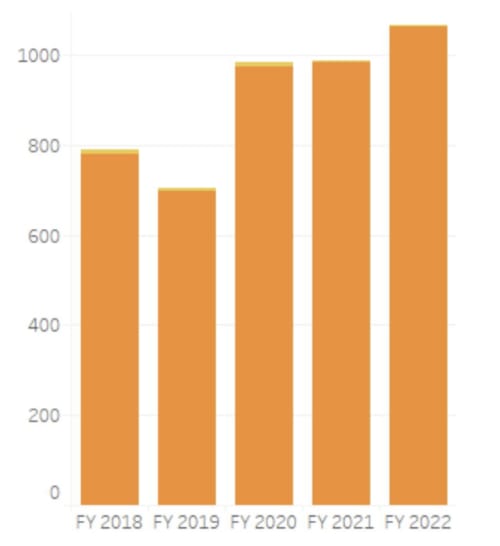

Chart 1: Drinking water investment is up

The good news is investment is up in our drinking water systems, which is where the reform started, and it’s getting better in wastewater, the second reform tranche.

Three Waters capital expenditure trends (2018-2022)

More critically, there’s been a big turnaround in how water authorities, mostly councils or council-controlled organisations, spend money on drinking water. In the past, they have tended to collect money from ratepayers to cover depreciation of their water infrastructure (as they’ve had to by law since 1996), but then they have spent much of that money on other stuff – from playgrounds to potholes.

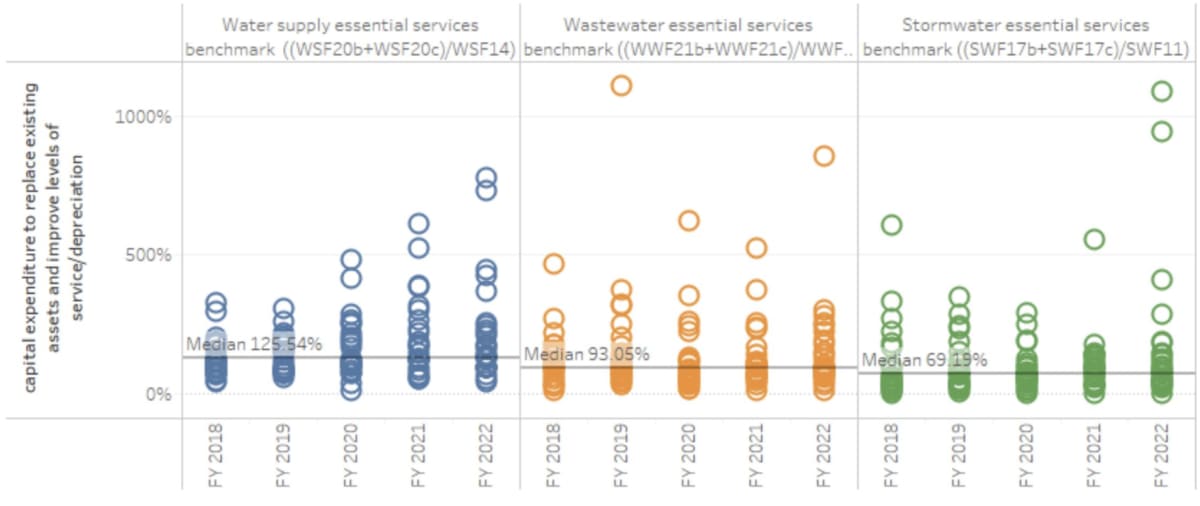

Now the National Performance Review figures show water authorities in the study are spending on average 125 percent of their drinking water depreciation money on (shock horror!) their drinking water infrastructure.

READ MORE: * Wellington’s water chaos a warning for all * Auckland’s drought: fate or failure

"This suggests that all else being equal, our water supply services across New Zealand would be expected to improve," Smith says. "This is a promising shift, when compared with reporting prior to this five year period."

In the 2017 fiscal year, for example, only 81 per cent of depreciation was spent on water.

In some places, Wellington for example, the numbers were far worse. As Newsroom reported in 2021, the percentage of depreciation spent on drinking water supply in the capital in 2019 was 36 percent, the figure for wastewater was 51 percent, and for stormwater 44 percent. Under-funding had been going on for decades.

Smith says the fact investment in wastewater and stormwater still trails depreciation is, in a bizarre way, a good sign.

"This suggests that the spotlight shone on drinking water networks through the Havelock North enquiry and the introduction of Taumata Arowai as a water service regulator has shifted the dial on investment in water supply – admittedly with some help from central government through Covid stimulus and reform support funding packages.

"It’s a really promising sign that regulatory changes are leading to changes in water authority expenditure. Now we need a similar shift in wastewater and stormwater."

Chart 2: Wastewater performance: we could do (a lot) better

As the chart above shows, investment in wastewater is starting to pick up. About time, according to the figures in the National Performance Review.

Wet weather overflows, a key measure of failure in the wastewater system, are still going up. These happen when heavy rain makes its way into the wastewater system and causes it to overflow, sending diluted sewage into streams, rivers, the ocean, or as we’ve seen in recent times, onto the streets and into people’s homes.

Number of reported wet weather wastewater overflows

The situation is made worse by the hodge-podge of reporting systems and regulations around wet weather overflows in different councils, meaning it's hard to know exactly what’s going on.

It's the same problem with wastewater treatment plants, particularly when it comes to the consents they have around what effluent they are allowed to discharge back into the environment, and whether they are sticking to the rules.

It’s not possible to compare the efficacy of different treatment plants, Smith says, because authorities monitor different parameters and set different consent conditions. “Development of standardised consent conditions is needed to enable meaningful comparisons. That would also assist in understanding impacts on water bodies, improving community engagement, lowering reconsenting costs and assisting consent compliance and enforceability."

The review report shows sixteen wastewater treatment plants, or nearly 10 percent of those whose details were provided to the report, were operating on expired consents; meanwhile, 20 percent of New Zealand’s total treatment plant consents are up for renewal over the next five years.

“Urgent action is needed,” Smith says. Roll on 2024 when Taumata Arowai takes on reporting for wastewater too.

Chart 3: Stormwater, very much the poor cousin

Figures from the review show stormwater is very much the poor cousin when it comes to anything being done to sort our failing infrastructure. The average investment in stormwater from the latest NPR report has been at only 70 percent of what is needed to cover asset depreciation, meaning the pipes and other infrastructure are getting more dilapidated every year.

The chart below looks complicated, but it's the median line that's important. Drinking water: 125.54 percent; wastewater: 93 percent; stormwater: 69 percent.

Drinking, waste and stormwater investment as a percentage of depreciation

At the same time, the way councils raise money for stormwater systems is “piecemeal”.

"Stormwater charging is really weird. We identified seven different rating approaches," Smith says.

"Lots of councils couldn’t tell us what people pay for stormwater because it’s bound up in general rates, and for those that can pull out stormwater charges, there’s a 10-fold difference between what people are paying, depending on where you live, from $33.54 to $409.12."

There are the same inconsistencies when it comes to consenting stormwater systems. Four of the councils in the review don’t have any consents at all; only seven are fully consented. Four survey respondents didn’t even know the answer to the question.

In the light of recent flooding, the approach for funding stormwater networks and keeping checks on their performance needs urgent attention, Smith says. Economic regulation will help provide transparency and a gauge as to what level of stormwater charging is going to ensure pipes are maintained and culverts don't collapse, she says.

“Is a tiny charge good or is a $400 charge good? What level can people afford and are they getting good value?”

Chart 4: Small centres (mostly) pay more than large cities

If you want cheap water, don’t live in Kaipara. Or Coromandel, Carterton or Western Bay of Plenty. These are all small places with big water costs.

If you use 200 cubic metres of water a year in Kaipara, you’ll be paying more than $2,300 a year in drinking and wastewater charges, compared with $600 in Palmerston North – a factor of four times.

As the chart below shows, Kaipara is the most expensive of the 32 water entities which participated in the 2022 review; another 32 didn’t take part, including Auckland’s Watercare. The average charge was $1100.

Water and wastewater charges, by territorial authority

Taking just the water supply charges (in blue, as opposed to the wastewater charges in orange, above), the difference between the cheapest ($244) and the most expensive ($1,209) is five times. But between urban centres, Smith says, water charges are less variable – with no major centre paying more than $617 for water supply, and $654 for wastewater.

The trouble for small centres is there is a smaller ratepayer base to pay for infrastructure, so each customer has to stump up more. In addition, bigger centres can achieve economies of scale not available to smaller regions, she says.

"This means the biggest cost burden is falling on people who generally earn less," Smith says. "Urban areas have higher average incomes than smaller towns and communities."

Ironically, the postcode lottery for water charges doesn’t just impact the households paying the most; there’s also a risk for those paying the least.

In Palmerston North, the council with the cheapest water charges, the issue of poor quality wastewater treatment processes breaching consents and polluting waterways, has been going on for more than a decade. The battle between the city and the regional councils over who should pay for existing problems and new wastewater treatment facilities has been going on – often in court – for just as long.

Where prices are considerably less than the national average you have to ask whether councils are achieving great efficiencies or whether they simply aren't spending enough to protect the environment and water quality.

"We need an economic regulator to tell us if these are good operators, or if there is a shortfall in necessary infrastructure spending,” Smith says.

Will the Three Waters reforms help? Smith thinks they should. On the one hand, consolidating the 64 councils and council-controlled organisations into four new publicly-owned Water Services Entities should see the costs and the charges spread more evenly across the areas covered by each entity, evening out the inequities.

At the same time, an economic regulator would hopefully provide more professional governance around infrastructure investment decisions.

And detaching the day-to-day running and performance of water entities from the consenting and compliance aspects (which will still be in the hands of regional councils post the reform) might help remove the conflicts of interests which can occur when the same or related local bodies find themselves acting as both poacher and gamekeeper – taking legal action over water quality consent breaches, but also having to pay for those breaches and invest in improving the system.

Chart 5: Could reform fix staff shortages?

A lack of people to fix NZ’s water infrastructure has been a problem for a long time, and it’s getting worse, not better.

Across the 32 water authorities which took part in the 2022 performance review (out of 64 in total), the number of employees has increased slowly since 2019, but vacancies have soared.

The number of staff is going up, but vacancies are going up faster

At the moment, the total number of staff employed in the three waters sector is more than 3200, plus contractors. But this varies dramatically across different councils. Mackenzie District Council has 4.5 full time staff working on water, Wellington has 272, and Watercare more than 1000.

Addressing the long-term lack of investment could mean an additional 6000 to 9000 skilled workers needed in the industry over the next 30 years, according to a workforce development strategy released last year. But attracting people into the profession has been difficult over recent years, Smith says, and the uncertainty around water reforms has made it worse.

"It’s all very well for Government and officials to tell people that these new entities will be kicking off in 2024 and you will have your job, but turn on TV and you see all that uncertainty, and that’s reflected in rising vacancy rates. Plus there is so much work to be done, it’s not particularly attractive."

Once the political uncertainty is resolved, however, Smith thinks the consolidation of smaller water bodies into bigger entities should increase the visibility of water as a career option.

"With economies of scale, you can have technical skills progression and subject area experts in a way you can’t with a small council."

And the sector needs more specialists, she says. Take the critical task of measuring greenhouse gas emissions from water assets and developing climate adaptation plans.

"Based on our information, only a third of all water service providers have assessed climate risks to all their water assets, and even fewer have in place adaptation plans to respond," Smith says. "Having technical staff focused on these area could be expected to be well beyond the resources of a small council, which might have just a handful of staff working on water services."

Blythe says New Zealand needs a national water workforce strategy.

"We need to know exactly what our workforce needs are for the next five to 10 years and how we can develop long term career pathways to attract and retain workers."