Joseph Shinn was sure, in his heart, that if we all just acted sensibly during the nascent stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, there would be plenty of toilet paper for everyone.

Most people, he says, knew what was right. Be human. Don’t race up and down the shelves gobbling up all the paper products. But most people also knew that most other people wouldn’t act in the interest of a greater good. Someone was going to start hoarding. And when someone else started hoarding, we were all going to start hoarding.

“I’m an economist, and I didn’t overdo it, but I went out and bought a little extra,” says Shinn, who has his Ph.D. in economics. “Because I knew that if everyone was going to be irrational, if I didn’t take these steps, I was going to fall into that issue.”

Meaning: He’d be “literally up s---’s creek.”

Illustration by The Sporting Press

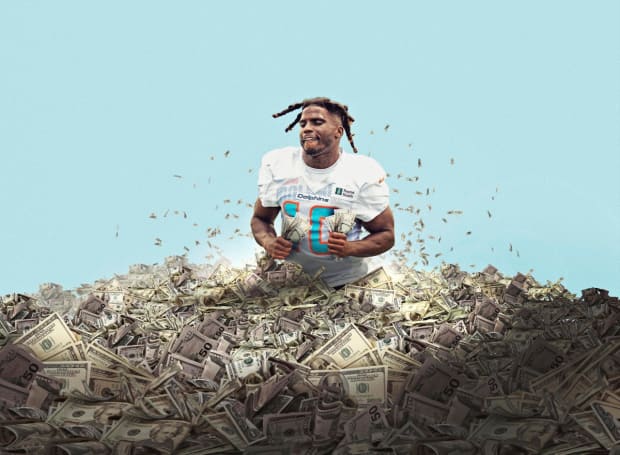

This is Shinn’s way of explaining what may have happened at the wide receiver position this offseason in the NFL. Shinn, who dabbles in the economics of labor markets, public health and housing, is also a fantasy football fanatic who teaches courses in sports economics at Rutgers. Like the rest of us, he observed the Jaguars’ signing of Christian Kirk—a player who has never logged a 1,000-yard season—to a four-year, $72 million deal. He saw the Raiders trade first- and second-round picks for Davante Adams, signing the 29-year-old to a five-year, $140 million contract. And he saw the Dolphins acquire Tyreek Hill, spending first-, second- and fourth-round picks in 2022, plus fourth- and sixth-round picks in ’23, and sign him to a four-year contract worth $120 million. (He’ll be the first receiver to earn $30 million in a season.) Then there was draft night. The Cardinals traded a first-round pick for Ravens receiver Marquise Brown, and the Eagles traded first- and third-rounders for A.J. Brown, signing him to a four-year deal worth $100 million. (Additionally: Six receivers were drafted in the top 20, including two by teams that traded up for the privilege. Only nine times in NFL history— two in the last three years—have that many receivers gone in the first round.)

Executives gobbled up veterans at the position seemingly without care for financial norms or precedent. The average wide receiver salary ballooned. For years, wideouts had been viewed as a luxury. Unscientific studies of past Super Bowl champions (specifically, the Patriots) revealed a cast of mostly anonymous role-playing pass catchers. Between 2000 and ’20, only once had a Super Bowl team employed the NFL’s leading wide receiver (Torry Holt, of the Rams, in ’01). But then Super Bowl LV featured top-of-the-line pass catchers like Hill, with the Chiefs, and the Buccaneers’ Mike Evans, Antonio Brown and Chris Godwin. Super Bowl LVI? The Rams’ Cooper Kupp, who led the league in receptions and yards; and the Bengals’ Ja’Marr Chase, the NFL Rookie of the Year.

The fear of missing out is real, and intense. The market’s ebbs and flows lead consumers to buy now, pay more and abandon potential best practices in the process. These waves of societal consumption, be it with new cars, foam mattresses, backyard pools or kettle bell weights, hit us one after the next. (Shinn cautions that housing is a bit different.) The same seems to be true of NFL GMs, who looked at the wide receiver market and then mashed the bright-red panic button.

“Everyone saw it happening quickly and said, ‘If everyone is going to do it, I better do it now—or else I’ll be without the quality player I need,’ ” Shinn says.

But while a sizable chunk of the league did pony up for elite receivers, a couple of the NFL’s best teams from 2021 decided they weren’t willing to pay the going price. Which means that this season will help point us toward some answers to these questions, and in real time: Are great receivers essential for a great offense, or will the system carry the day? Or, in short, did all these teams really need to run to the supermarket and clear out the aisles?

While this offseason’s run on receivers was a leaguewide trend, let’s momentarily narrow the lens to four teams: the 49ers, Packers, Titans and Dolphins.

Each of the above runs a version of the same offense, which was recycled in the NFL by Kyle Shanahan, coach of the 49ers. Shanahan learned the offense from his father, Mike, and Mike’s offensive line coach, Alex Gibbs, who together ran the stretch-running, play-action-heavy scheme en route to two straight Super Bowl victories with the Broncos in the late 1990s. Packers coach Matt LaFleur worked with Kyle and Mike Shanahan in Washington, and then with Kyle in Atlanta, and he brought the offense to Tennessee for a year as coordinator before taking the Packers’ top job in 2019. The Titans simply retained the offense after LaFleur left, handing it down to their next two play-callers: first coordinator Arthur Smith (now coach of the Falcons) and then Todd Downing, their current coordinator. Finally, first-year Dolphins coach Mike McDaniel was the younger Shanahan’s longest-tenured associate, having been Kyle’s run-game guru for more than half a decade at various stops.

Despite running similar systems, each team behaved differently when it came to the wide receiver gold rush. The Packers traded away Adams, far and away Aaron Rodgers’s favorite target for the past four seasons, and added journeyman free agent Sammy Watkins plus two rookies, second-rounder Christian Watson out of FCS program North Dakota State and fourth-rounder Romeo Doubs of Nevada. The Titans traded away Brown, their leading receiver in each of his three NFL seasons, and drafted a replacement, Arkansas’s Treylon Burks, in the first round. The 49ers, meanwhile, refused to trade away their star wide receiver, Deebo Samuel, despite a bustling market and Samuel’s open desire to leave San Francisco. The Dolphins traded for Hill, less than a year after drafting similarly speedy Jaylen Waddle with the 2021 draft’s sixth pick.

Scoping this scene, similar conclusions were reached by three people who spoke to Sports Illustrated: an NFL personnel executive, a coach who’s deeply familiar with the Shanahan offense and a high-profile agent (SI granted them anonymity in exchange for their candor). While the moves may look like they were made under the same roster-building logic, they could easily be separate reactions to individual problems. The 49ers, for example, likely wanted to keep Samuel because they planned to start second-year quarterback Trey Lance, who would benefit from the assistance of elite pass-catching talent. The Dolphins, who are trying to ignite the career of QB Tua Tagovailoa, the fifth pick of the 2020 draft, were willing to pay the price for Hill. The Packers have Rodgers and can trust that he will buoy the talent around him. And, as with any situation in the NFL, there is always a murkiness as to whether ownership wants to hand over market-altering money. Replacing Brown (who would go on to say that the Titans’ contract-extension offer to him was far below what he ultimately attained in Philadelphia) with an unproven rookie is a risk, but there’s an argument that it makes more business sense for the Titans.

The agent who spoke to SI added that the receiver market had been unrealistically stagnant for too long, and that the position was due for a market correction. Now, Hill and Adams are among the 20 highest-paid players in the sport for 2022 (Nos. 13 and 17, respectively). Along with left tackle, pass rusher and cornerback are often considered the premium non-quarterback positions. Yet, Hill and Adams are each set to make as much as or more than T.J. Watt and Myles Garrett, the two best pass rushers in football; and each is set to make nearly $10 million more in ’22 than the league’s highest-paid corner, Green Bay’s Jaire Alexander.

Whatever the explanation, this cluster of decisions helped electrify the market. Backdropped against a much larger and far-reaching clamor for wide receivers, the variance in decision-making and homogeneity in offensive philosophy between these four teams gives us a chance to discover what the value of a receiver is. If the Dolphins rapidly improve, if the Packers and Titans falter, if the 49ers ultimately regret passing on the chance to trade Samuel, the outcome will influence the future of league behavior.

Consider: Roughly 40% of the league’s offensive play-callers are somehow connected to the Shanahan offense and are borrowing heavily from its concepts. Imagine being able to prove by some pseudo-concrete measure that an offense produces its playmakers, and not the other way around. Or, imagine demonstrating a desperate need for certain talent to make the most popular offensive scheme in the NFL function properly. Returning to Shinn’s metaphor: Imagine a perpetual toilet paper shortage that, for some teams, lasts not months, but years.

When it comes to trading high-profile wideouts, there’s a grim track record for teams on the receiving end. Odell Beckham Jr. to the Browns (for a first- and third-round pick), Julio Jones to the Titans (second- and fourth-round with a sixth-rounder coming back), Antonio Brown to the Raiders (third- and fifth-round), Percy Harvin to the Seahawks (first-, third- and seventh-round), Roy Williams to the Cowboys (first-, third- and sixth-round) and Joey Galloway to the Cowboys (two first-rounders) all cast a heavy shadow over the relatively few successful trades (Stefon Diggs to the Bills, DeAndre Hopkins to the Cardinals, Terrell Owens to the Eagles . . . ).

One general manager who did not select a wide receiver in the early rounds of the 2022 draft said that he lamented that fact simply from an economic standpoint. Here was a way to try to get something cheap. Example: The first receiver drafted in ’22, USC’s Drake London, is making roughly $5.3 million per year on his rookie contract for the Falcons, which is less than, for instance, Jets veteran slot receiver Braxton Berrios. London could be just as effective as the pass catchers that some teams are paying $30 million a year, but at less than 20% of the cost.

Even beyond the first round, the draft has produced no shortage of stars at the position over the past couple of seasons. Samuel and Brown, plus the Seahawks’ DK Metcalf, Commanders’ Terry McLaurin and Steelers’ Diontae Johnson all went on the second day of the 2019 draft. The ’20 draft’s second round included Cincinnati’s Tee Higgins, Indianapolis’s Michael Pittman Jr. and Pittsburgh’s Chase Claypool. And the rookie wage scale locked them into contracts that average roughly $1 million per season over four years, with no chance to renegotiate until after their third year in the league.

In that way, the rookie route is a means to get the good toilet paper at a pre-pandemic price, not from some seedy price-gouger on Craigslist. This attitude, which seems to be sensible for any market-savvy GM adept at noticing trends, makes the exploding veteran receiver market even harder to understand.

In fact, we have a fairly good idea of how likely a given team is to hit on a first-round wide receiver, and it appears to be getting better. Of the receivers drafted in the first round between 2000 and ’19, just 27% have reached the Pro Bowl at any point, over the course of 20 seasons. For the ’20 and ’21 drafts the rate is the same, 27%—three out of 11—already.

This could explain why the GM that SI spoke to was sore about missing out. Or why, for instance, the Saints traded for additional draft capital in 2022—which many viewed as offering a weak overall draft—to select Ohio State’s Chris Olave.

Jasen Vinlove/USA TODAY Sports

Or, think of it this way: The Titans took a first-round pick in exchange for Brown, knowing they would draft Burks. Both are signed to four-year contracts. But Burks’s deal is worth 14% of the average annual value and 25% of the total guarantees of Brown’s . . . with a 27% chance of being almost as good.

“[Some teams] are making clear economic decisions,” says Donn Johnson, chair of the economics department at Quinnipiac. “Receiver prices are hitting $30 million . . . or you can draft one in the first round [and] you’re not paying anything close to that amount of money. The calculation in their head is that they may only have a 50% chance of hitting, but they’re only paying that person $4 million [annually].”

Back in 2008, Johnson and his co-author, Matthew Rafferty, were putting the finishing touches on an economic paper entitled “Is the NFL Draft a Crap Shoot? The Case of Wide Receivers and Running Backs” when Rafferty, a revered economics professor at Quinnipiac, died. (Johnson plans to finish the paper with the help of Ramapo College economics professor Alexandre Olbrecht, a fellow football data obsessive.) And Johnson and Rafferty found that the information that exists for scouts is a fairly solid determinant in future success. For example: A team that drafted a player high on the board of Pro Football Weekly draft savant Joel Buchsbaum—someone with, say, an 8 out of 9 on Buchsbaum’s grading scale—had an 8.3% greater chance of landing a future Pro Bowler than if they’d drafted a 7 on Buchsbaum’s scale. This is their data-driven way of saying that most of the information the draft machine produces-—a consensus of scouting and executive groupthink, along with combine measurements, collegiate stats and relevant athletic information—can give you a fair educated guess at receiver success.

Another recent study by Conor McQuiston, an analytics intern for the Cardinals, shows that wide receivers drafted in the first round tend to outperform second-round picks only slightly, extending the position’s range of value beyond a first-round pick. A third study, by Pro Football Focus data scientist Timo Riske, shows that receivers take less time to get used to the NFL and succeed faster than most of their positional counterparts.

Today’s college game “features much more throwing,” says Johnson. “It’s helping [NFL] teams gauge players better than in the past.”

This drives at the heart of what Shinn was saying about toilet paper. NFL teams know this information. They know the hit rates. They know the acclimation rates. They know that, on average, for every four financially responsible swings they take at the position via the draft, they’ll have a player they are paying a fraction of what they’d have to spend on Adams or Hill, with a statistically similar output. They know, in their hearts, the right thing to do.

In certain circumstances, teams cannot help themselves. And yet, sometimes, feeling like you’re up s---’s creek is the catalyst for a brilliant decision. If economists can get caught up in the toilet paper rush, and the Bucs and the Rams have been hoarding receivers for years, how bad can it really be?