The Bank of England base rate has increased steeply from 0.25% in January 2022 to 4.25% in March 2023. More than 4 million UK households now have significantly higher mortgage costs as a result, while also dealing with the impact of soaring prices for other items such as food and energy.

This pain will only continue as those households that secured low fixed rates before the recent rake hikes start to roll off their current mortgage deals in the coming months and years. But Bank of England data shows that many UK borrowers expect rates to fall back to recent lows again by 2027. Signals from central banks, continued rising inflation and a relatively improved economic picture, however, mean that such expectations are unlikely to be met any time soon, if ever.

Commercial banks look at a range of factors when setting mortgage rates, particularly for fixed-rate mortgages. For example, mortgage lenders tie their rates closely to long-term (typically five-year) government bond rates because this is where they would invest despositors’ money if they weren’t lending it out to mortgage borrowers. Therefore, when the cost of borrowing for government increases, so do mortgage rates.

Banks also factor in additional risk (called a risk premium) to their mortgage rates. Unlike the Bank of England or the government, households and individuals can default as their mortgage repayments hinge on their financial wellbeing. When calculating this risk, lenders typically consider how much they are lending you versus the deposit you have for a home (called the loan-to-value or LTV ratio), as well as your credit history, ability to make your repayments and future job stability.

The Bank of England’s base rate also plays a key role in your mortgage rate. This is the single most important interest rate in the UK economy because it determines how much the central bank pays the commercial banks that hold money with it. As such, it sets the benchmark for the cost of borrowing and lending and so it determines how banks calculate what you must pay in mortgage interest.

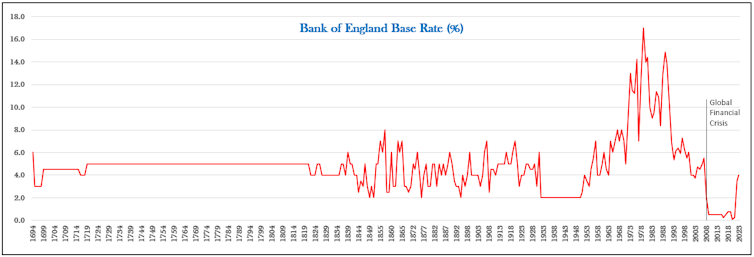

For the 13 years between 2009 and 2021, interest rates were historically low. The Bank of England base rate has not been at this level at any other time in its 325-year history.

UK base rate over time:

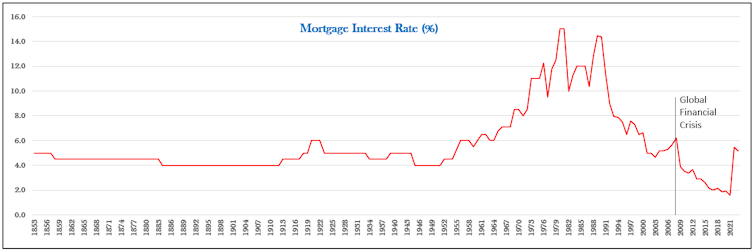

Similarly, rates for new mortgages had never been below 4% before this time, at least since banking records began in 1853.

Changing mortgage rates:

People that bought their first home during this period have never experienced anything other than historically low mortgage rates. This means that the current soaring prices and increasing mortgage costs has been even more of a shock to the system for this group.

There also seems to be an expectation among many borrowers that interest rates will return to historical lows. In a 2022 survey by the Bank of England, 40% of the participants (excluding “don’t know” responses) said they expect the base rate to be below 2% by 2027 – a level rarely seen even in previous low rate periods.

Why mortgage rates will defy expectations

So what should you expect from mortgage rates in the coming months and years? Certainly not a return to low rates.

Central banks across the world have been increasing their interest rates to tackle the sharp surge in inflation. Many central banks want inflation to be around 2% but it has been recently five times that in the UK and in the European Union. While inflation (caused by recovering economic activity post-COVID, supply chain bottlenecks and the Ukraine invasion) has started to slow down, interest rates are unlikely to fall soon for three reasons.

First, at least in the UK, the Bank of England will need to monitor inflation in the coming months – particularly after the most recent unexpected increase in the headline rate to 10.4% in March 2023.

Second, central banks have already been criticised for failing to react quickly enough before last year to suppress inflation. Rather than large interest rate hikes that we saw in the late 1970s, they have chosen to steady increases. Changing this course too quickly could cause credibility issues because it might make them seem indecisive and erratic.

Third, if central banks reduce rates from where they are by a small margin it could make very little difference on the ground for borrowers, but could give mixed signals to the markets. Again, this would dent their credibility.

Fighting inflation

So does this mean central banks’ have completely given up on the effectiveness of rates as their most trusted inflation-fighting tool? Two recent incidents suggest they are certainly more willing to try methods other than rate cuts at the moment.

When the Bank of England had to intervene following the UK’s mini-budget saga to support financial institutions, it used other means, namely quantitative easing. It purchased sovereign bonds to increase the flow of money into the financial system rather than lowering rates.

More recently, amid the ongoing financial turmoil around the Credit Suisse takeover, the European Central Bank and the US Federal Reserve have gone ahead with increases in their key policy rates.

Further, the ECB has continued to scale back its quantitative easing programme and declared the European banking sector to be resilient, with robust levels of capital and liquidity. These announcements reflect a lack of desire to use rate cuts to ease market turmoil.

So, there is no sign that any of the major central banks plan to lower interest rates any time soon. While the governments’ cost of borrowing in some of these countries have come down lately, compared to the last decade they are still relatively high. Since interest rates for businesses and households are decided partly based on these bonds, it means mortgage payments may not come down significantly in the foreseeable future either.

And of course, the improving economic outlook in both the UK and Europe – with better growth figures now expected for later this year versus four months ago – also reduces pressure to cut interest rates.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.