Tightened Reserve Bank LVR mortgage deposit rules, and impossibly restrictive Kāinga Ora price and salary caps are keeping first home buyers out of houses, experts say. The recent CCCFA debacle is just a sideshow.

Last week, the Government righted a wrong. Lending restrictions introduced in December under the Credit Contracts and Consumer Finance Act (CCCFA) and intended to stop unscrupulous loan sharks from saddling borrowers with debt they couldn’t afford had had the unintended consequence of seeing legitimate bankers treat many people wanting to borrow money like criminals.

Faced with the possibility of a $200,000 personal fine if they lent to someone who couldn’t pay, bank bosses started asking for crazy amounts of information about potential borrowers’ personal financial affairs before giving them a mortgage - anything from all the coffees they had bought over the past three months, to any discretionary Kiwisaver payments they made.

Many creditworthy customers couldn’t get loans at all. First home buyers were the worst hit, since they were potentially the most risky borrowers.

It seems Consumer Affairs Minister David Clark listened to the backlash from banks, mortgage brokers and customers - including 10,000 people who signed a petition. Late last week he announced changes to the new CCCFA rules that will hopefully keep the pressure on the loan sharks but allow banks to lend with more normal levels of information.

The details aren’t fully-formed, but changes should come in in June, Clark says.

Joss Lewis from apartment developer Ockham Residential was just one of many Newsroom spoke to who welcomed the news.

“Changes to CCCFA had to happen, there were just so many completely illogical things going on.”

Jeff Kerwin, co-founder and director of Hamilton-based Nest Home Loans, says the Government sent the draft proposals for consultation last year and was warned about the unintended consequences, but took no notice.

“The banks said this would happen. The Government didn’t listen, passed the legislation, and lo-and-behold this is what happened.

“The aim was to target predatory lenders, but there’s no indication banks have any predatory lending habits.”

Problem solved for first home buyers? Not remotely, say the experts.

"It’s certainly a step in the right direction and great to see some practical, common sense changes being proposed, but first home buyers have a whole range of hurdles to overcome,” Lewis says.

“The main issue we see time and time again with first home buyers is the struggle to pull together a 20 percent deposit.”

And that problem is getting worse, not better.

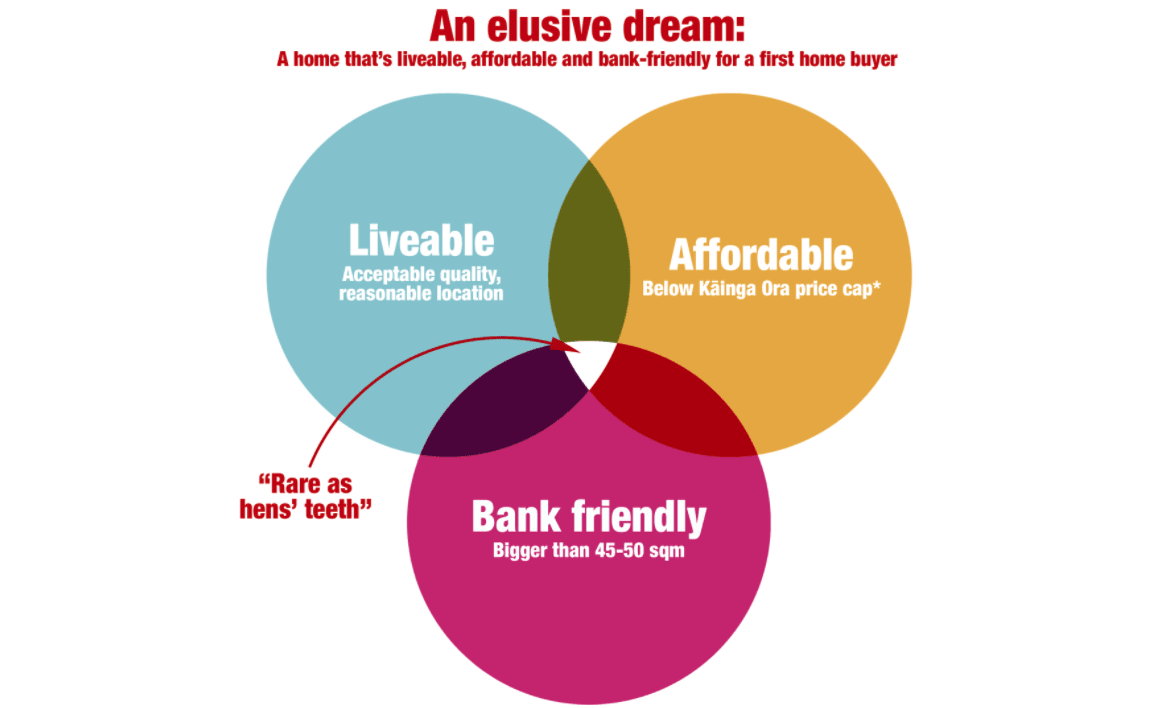

It’s complicated, but there are three big problems Newsroom sees particularly impacting first home buyers' ability to get into the market. First: the Reserve Bank’s well-intentioned but increasingly restrictive loan-to-value (LVR) ratio restrictions on the banks. Second: Kāinga Ora’s crazily-out-of-line-with-reality First Home Grant and Loan schemes - schemes whose very raison d’etre is to help people into homes. And third: banks’ long-harboured, but not totally logical, unwillingness to lend on apartments, particularly small apartments.

1) LVR restrictions tighten

Loan-to-value restrictions were first introduced by the Reserve Bank in 2013 as a temporary measure to improve bank lending practices. Restricting the number (or more accurately the value) of low-deposit mortgages a bank could have on its books to a certain percentage of the total value of its mortgages, was seen as a way to improve banks’ financial stability.

Less risky lending, less chance of banks getting into trouble.

For most of the decade since LVRs were introduced (as a temporary measure at first - previously RBNZ had said they were too intrusive), the restrictions for banks lending to people wanting to buy a home to live in (“owner-occupiers” in RBNZ speak) have varied between 10 percent and 20 percent of a bank’s total lending being allowed to be be to borrowers with a deposit less than 20 percent of the house value.

Banks get to choose which people for whom they are prepared to go below the 20 percent deposit mark. The trouble for first home buyers is they are by definition more risky for banks - they probably don’t have much of a credit history and they don’t have any other property the bank can use as security for their loan. So if there are restrictions on how many high-risk loans a bank can hold, first home buyers aren’t going to be top of the list.

Of course there is a school of thought that it's no bad thing to make people save up for a 20 percent deposit. But with house prices so high, a 20 percent deposit can be a hell of a big sum to raise.

Estate agents say there are a lot of people - young people recently out of university with good jobs, for example - who could service a loan on a $1 million house, but don’t remotely have $200,000 in the bank.

Before Covid hit, and from March 2021 onwards (LVR restrictions were lifted at the height of the 2020 phase of the pandemic), the RBNZ’s rule was for banks to have no more than 20 percent of their mortgage book in high loan-to-value ratio loans.

But on November 1 it moved that to 10 percent.

“Our analysis indicates house prices are above their sustainable level, and the risks of a housing market correction are continuing to rise. The proposed tightening of LVR restrictions will over time help reduce the number of highly leveraged borrowers and help to build resilience in the financial system,” then Deputy Reserve Bank Governor Geoff Bascand said at the time.

What with that, and the CCCFA changes which came into force a month later, the banks practically stopped lending to first home buyers, Kerwin says.

“As soon as the RBNZ introduced the new restrictions, the lending just stopped - every first home buyer was immediately cut out,” Kerwin says. “Banks didn’t have any choice in the matter - they had to get their loan books lower.”

The situation is starting to ease, he says, and he thinks over the next month banks will be in a position to start taking on more first home buyer loans.

Meanwhile the restrictions and other factors, including rising interest rates, has dampened the housing market - which is what the Reserve Bank wanted.

But first home buyers will still be the ones missing out.

“Banks will still be able to write only half the number of low deposit mortgages they used to be able to,” Kerwin says. “It’s counter-intuitive when the Government’s stated goal is to help first home buyers.

2) Kāinga Ora loans and grants “irrelevant”

Newsroom has written a fair amount about the Government’s Kāinga Ora loans and grants schemes, which are intended to help first home buyers into homes by:

- guaranteeing loans at a 5 percent deposit (the First Home Loan scheme). The loans allow borrowers to use gifted money (Mum and Dad/Granny/Uncle Walter) for that 5 percent deposit, when commercial banks expect at least 5 percent of so-called “real savings”. And importantly, because the loans are guaranteed by the Government, First Home Loans are excluded from the Reserve Bank’s LVR restrictions on low-deposit lending described above, meaning banks in the scheme are confident to lend without getting themselves offside with RBNZ.

- allowing first home buyers who have been making KiwiSaver contributions for 3-5 years to get up to $10,000 (for a single person, $20,000 for a couple) from the Government to help towards a deposit (First Home Grant).

The problem with both schemes is that the eligibility caps both on the house price and on the potential buyer’s earnings are so low that very few people or houses meet the criteria, except in a few less popular regions.

For example, to qualify for a loan or grant in Auckland, the house you want to buy has to be under $625,000. The lower quartile house price (the indicator of the most affordable 25 percent of the market) for Auckland in January was $922,000.

“There are no homes you can get in Auckland for $625,000,” says Andrew Murray, chief executive of Auckland real estate company Apartment Specialists. “The loans and grants are irrelevant.”

Similar story from mortgage broker Jeff Kerwin. He says five years ago a lot of Nest customers bought their home using a Kāinga Ora loan and/or grant. Now it’s just a few in regional centres - and even that’s rare.

That’s crazy, given how tough things are for first home buyers, with the LVR restrictions and, until June, the CCCFA rules, he says.

“The first home product is exempt from the banks’ rules around 10 percent LVR, so technically the banks could write as many of those mortgages as they like and not affect their books, but the Kāinga Ora criteria mean effectively they don’t write any.”

The Kāinga Ora schemes should have a crucial role to play getting first home buyers into properties while the fundamental issue - supply - is sorted, Kerwin says.

“When supply is fixed, the government will no longer need to tinker with demand by cutting first home buyers out of the market completely. But I realise we can't build 50,000 houses overnight, so an interim solution would be to change the eligibility criteria for the First Home Loan, so that it becomes more accessible and relevant to the marketplace.”

Read more about the problem with Kāinga Ora loans and grants in Newsroom’s stories from last year.

Governments Kāinga Ora home loan mortgage scheme ‘totally redundant’ and Higher house price caps would have helped only a few hundred first home buyers.

Since we wrote these stories the only thing that has changed is house prices have gone up, making the scheme even more irrelevant. The Government has made no move to lift the caps.

3) The apartment conundrum

Newsroom has also been banging on about the problems first home buyers have purchasing apartments, particularly small apartments, for a while.

In March last year, under the headline The lending trap: Small apartments, big deposits, we wrote: “banks are demanding 50 percent deposits from customers wanting mortgages on small, cheap apartments, making the most affordable homes unaffordable for the very people Government wants to help into the property market - first home buyers.”

After problems in the past with people who bought small apartments ending up losing their shirts when they turned out to be leaky, banks are wary. But agents like Apartment Specialist’s Andrew Murray say banks fail to distinguish between badly built apartments and solidly designed ones - or ones which have been substantially refurbished following leaky building problems.

Instead they are all lumped together in the too hard, too risky basket.

Murray says some banks have dropped their size restrictions down a little over the last year - ANZ is now prepared to lend on an apartment bigger than 38 square metres - as opposed to 45 or 50 sqm, without asking for a 50 percent deposit.

But they are still far less likely to lend on an apartment than a house - and when the banks are choosing which borrowers to give low deposit mortgages to under the LVR rules, it isn’t people buying apartments.

Murray says that’s about profits for the banks.

In general, apartments cost less so the loan sizes are smaller, but banks still have to do the same amount of work to get an apartment mortgage across the line, he says - more in fact because there are body corporate rules to check out and more investigation needed around, for example, water tightness.

“So if I’m a bank and I’m choosing between a $400,000 apartment mortgage and $900,000 for a house, I’ve got more than double the income on the house and more than double the work on the apartment.

“I make more profit off the house.”

Once again, lower income first home buyers miss out - even when they are purchasing a good quality apartment and have enough income to service their mortgage.

“Overseas it’s not like that,” Murray says. “The Government should say loan-to-value ratios should be treated the same for apartments as for houses.”

This is even the case with new-build apartments, which should in theory get preferential treatment because, like with Kāinga Ora loans, new builds are exempt from the Reserve Bank loan-to-value restrictions.

Not for apartments, says Ockham’s Joss Lewis. Most of what she sells is off the plans, but “no one is getting under 20 percent”, she says.

“For young people to save that amount of money in today’s environment is just so tough. A lot of people we meet have 10-15 percent now but they are really going to struggle trying to get to 20 percent.”

A buyers market - or almost

It’s ironic, says Scott Dunn, a licensed real estate broker with City Sales, which specialises in Auckland apartments, because the market is more favourable for buyers than it’s been in a decade.

“Stuff is difficult to sell at the moment,” he says. “Sometimes we are getting just one potential buyer turning up at an open home; sometimes no one at all.” In October last year, Barfoot & Thompson’s auctions were seeing two thirds of properties sold, that dropped to a third in December and fell to under a quarter at the latest auction, Dunn says.

“Covid has hit us like a freight train; people are too scared to go and look at units. Then there are the interest rate rises and the banks with the LVRs.

“We are saying, ‘if you are a first home buyer with a deposit, don’t wait.”

But if you haven’t got a deposit? “Sometimes it feels like they go one step forward [in terms of the conditions improving for first home buyers to be able to get a property], and then they tumble back to the bottom of the hill. A lot of people we’ve been working with have been told ‘No’ so many times they have just given up.”