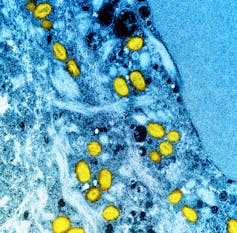

Monkeypox virus, or MPXV, is an emerging threat to public health. The World Health Organization recently declared the current outbreak a global public health emergency.

For decades, several African countries have experienced ongoing outbreaks of MPXV, driven primarily by contact with animals and transmission within households. However, before last year, most people in Europe and North America had never even heard of the disease. That was until the current outbreak among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men.

Debates over the epidemiology of MPXV

Over the past several months, a controversy has raged about whether it’s OK to say that the current MPXV outbreak is primarily affecting gay and bisexual men, and that it is primarily being spread through close personal contact, such as sex.

As a social and behavioural epidemiologist working with marginalized populations, including gay and bisexual men, I believe it’s important that people know that sexual and gender minority men are the primary victims of this MPXV outbreak. I believe this knowledge will help us end the outbreak before it bridges into other communities.

For reference, more than 90 per cent of cases in non-endemic countries have been transmitted through intimate sexual contact, and the vast majority of cases are among gay men. Very few cases are linked to community transmission.

While these statistics are undisputed, some have feared that identifying sexual behaviour as the primary cause of current MPXV transmission would dampen the public health response. Others have warned that connecting MPXV to an already stigmatized community will worsen stigma towards gay sex.

Non-sexual transmission is possible, and a considerable threat

It is true that MPXV can transmit through more casual contact and through fomites (inanimate objects on which some microbes can survive, such as bed linens, towels or tables).

However, months into the current outbreak, we have not seen these routes emerge as important pathways of transmission. This may be due to changes in the fundamental transmission dynamic of MPXV or due to enhanced cleaning procedures implemented in response to COVID-19 in places such as gyms and restrooms.

Why it’s crucial to know MPXV affects gay and bisexual men

Informing the public about MPXV is important because public opinion plays an important role in shaping public health policies, such as who gets access to vaccines and what interventions are used to stop disease transmission.

A recent study conducted by my team aimed to demonstrate the importance of public health education by asking Canadians to participate in a discrete choice experiment.

We asked participants to choose between two hypothetical public health programs across eight head-to-head comparisons. Descriptions for each hypothetical program identified the number of years of life gained by patients, the health condition it addressed and the population it was tailored for.

From our analyses of this data, we learned a lot about how the public wants public health dollars to be spent and how their knowledge and bias shapes these preferences. There were five major takeaways:

People preferred interventions that added more years to participants’ life expectancy. In fact, for one year of marginal life gained, there was a 15 per cent increase in the odds that participants chose that program.

We found that people tended to favour interventions that focused on treatment rather than prevention. While this approach is emotionally intuitive, large bodies of evidence suggest that it is more cost-effective to prevent disease than to treat it. As the old saying goes: An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

People generally preferred interventions for common chronic diseases — such as heart disease, diabetes and cancer — and were less likely to favour interventions for behaviour-related conditions, such as sexually transmitted infections.

People generally preferred programs focused on the general population as opposed to those tailored for key marginalized populations. In fact, people were least likely to prefer interventions tailored for sexual and gender minorities.

The bias against behavioural interventions and those tailored for key populations was overcome when the programs addressed a health condition that was widely understood to be linked to the population the program was tailored to. For example, people were more likely to support interventions for sexually transmitted infections when these interventions were tailored for people engaged in sex work or for gay and bisexual men.

This study highlights why it is important to educate the public about health inequities. People are smarter, more pragmatic, and more compassionate than we give them credit for. If we take the time to share evidence with them about the challenges that stigmatized communities face, they will be more willing to support policies and efforts to address these challenges.

Ending MPXV quickly is critical, especially since the virus has the potential to evolve in ways that could make the disease more infectious. Protecting gay and bisexual men first, protects everyone.

We should, of course, always be aware of the potential harms and the corrosive effects of stigma. However, in public health, honesty really is the best policy.

Kiffer George Card receives funding from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, the Canadian Research Coordinating Committee, Michael Smith Health Research BC, and Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. He is affiliated with Simon Fraser University's Faculty of Health Sciences, The Institute for Social Connection, The Community-based Research Centre, the GenWell Project, The Island Sexual Health Society, and the Mental Health and Climate Change Alliance.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.