Board games have been having a bit of a cultural moment. They experienced a resurgence of popularity at the beginning of the pandemic. A Statista report projected the total overall board game market might reach US$12-billion by 2023.

It makes sense that board games gained popularity during the pandemic. Board games can provide relatively affordable, reusable, home-based entertainment. Scrabble was designed by Alfred Mosher Butts during the Great Depression. Eleanor Abbott created Candy Land after her contracting polio and spending extended time in the hospital during the epidemic in the United States.

I have loved board games my whole life and in the last 10 years spent my time browsing shops for the newest releases, growing increasingly addicted to watching board game channels on YouTube and collecting games — a collection which has taken over several rooms in my home.

I regularly noticed that these friendly local game shops were filled with mostly white men, often on their own, wandering the stacks. It made me wonder, why is board gaming so white and male?

As a doctoral student at X University and York University in their joint communication and culture program, I have noticed a lack of contemporary scholarship on board games, as most game scholarship focuses on video games.

To fill this gap, I decided to spend the last four years of my life delving into the industry.

Socially shaped and constructed

Board gaming, like many other cultural spheres, has been socially shaped and constructed, with products being created for an imagined audience. The imagined audience for board games is, most often, a cis, straight, middle-class able-bodied white man.

The result of this social shaping has been that board gaming spaces have, over time, have become an exclusive preserve for this default, imagined audience. Sometimes, this kind of social shaping, intentionally or not, can create a vicious circle of exclusion for other identities.

As I talked to people in board gaming communities and examined the games themselves, I realized that there were big, systemic social, labour and economic issues that were limiting the wide-spread adoption of board gaming and market growth.

My research argues that one of the key factors facing board gaming is the homogeneity of the current board game design labour pool and limited representation on the products themselves.

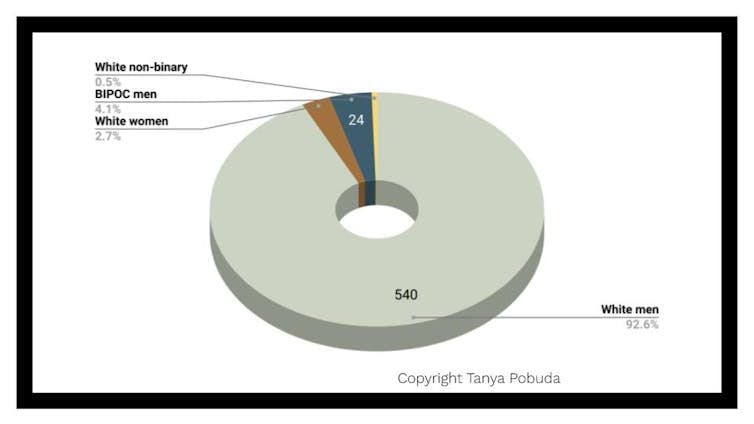

I found that 92.6 per cent of the designers of the 400 top-ranked board games on BoardGameGeek were white men.

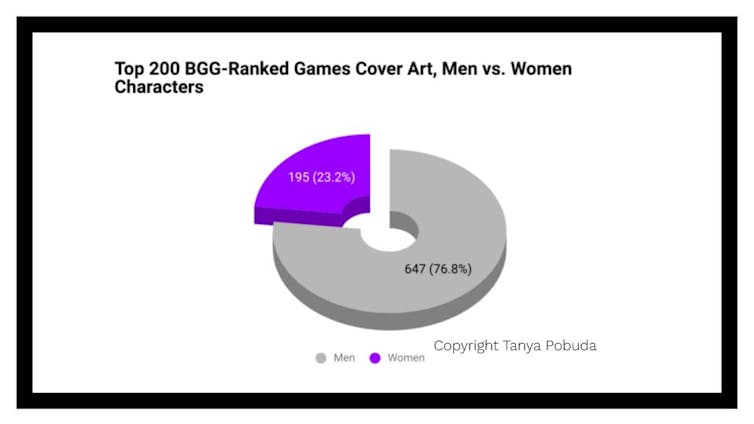

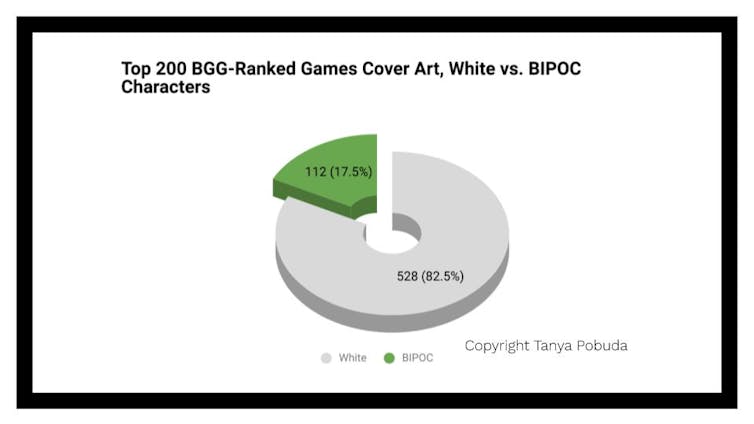

The cover art images on the boxes of the top-ranked 200 BoardGameGeek ranked games with games such as Gloomhaven (2017),Marvel Champions: The Card Game (2019), Terraforming Mars (2016) and Through the Ages: A New Story of Civilization (2015) skewed heavily toward white-presenting males. Of the total 1,974 figures analyzed during my board game cover art analyses, white male imagery was predominant.

Images of men and boys represented 76.8 per cent of the human representation on covers, or 647 images in games such as Great Western Trail (2016) and War of the Ring: Second Edition (2012), compared to 23.2 per cent of the images of women and girls, which represented only 195 of the images counted as in games with more gender representation like Arkham Horror: The Card Game (2016) and Pandemic Legacy: Season 1 (2015)

White imagery was found on 82.5 per cent of the images or 528 compared to BIPOC imagery which made up only 17.5 per cent of the images, or 112 total images.

Representation matters

A lack of representation sends a message to potential audiences. But does this lack of representation matter to current board gamers?

I conducted an online survey of 320 respondents in late 2020. In total, 70.7 per cent of respondents shared that they play board games at least once a week. More than half (53.5 per cent) of the sample have been board gaming for 11 years or more.

I tried to get a diverse sample through exhaustive recruitment efforts as I was looking to hear from voices that were not often heard from in other board game surveys.

I got back a set of respondents who were mainly from North America (73.8 per cent). The majority of survey respondents identified as women at 60.4 per cent, including trans women which represented 4.9 per cent. More than a quarter of my survey respondents identified as men at 25.3 per cent and 9.4 per cent identified as non-binary.

Most of the respondents were white (74.9 per cent), while 20.4 percent identified as BIPOC. More than half of the sample (52.8 per cent) identified as being part of the 2SLGBTQiIA+ community.

The survey respondents shared that gender and racial representation did matter to them, in fact it mattered a lot. Respondents agreed or strongly agreed (80.2 per cent) that board gaming has a problem with a lack of equitable gender representation in games design and 84 per cent agreed or strongly agreed that board gaming has a problem with a lack of equitable racial representation in games design.

Another overwhelming majority (83.6 per cent) agreed or strongly agreed that board gaming has a problem with a lack of equitable gender representation in board game artwork. Similarly, 84 per cent of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that board gaming has a problem with a lack of equitable racial representation in board game artwork.

The current reality? Despite straight white males making up roughly 25 per cent of the U.S. population — the U.S. being one of the world’s largest consumer markets and straight white males being an even smaller portion of the global market — they currently make up about 80 per cent or more of the representation in board games.

Do these realities — the board game industry’s persistent focus on a small demographic and its skewed representation on the products toward this small population — create the necessary conditions for market growth and expansion of the board game industry?

The answer can only be no.

Tanya A Pobuda receives funding from Edward S. Rogers Sr. Graduate Student Fellowships.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.