Illinois’ new assault weapons ban is only days old, but it’s already on uncertain legal footing.

Republican lawmakers and gun shop owners say so. But so do constitutional law scholars.

Illinois Democrats who crafted the legislation — which took effect Tuesday and was enacted in response to the Highland Park Fourth of July parade mass shooting in which seven people were killed — say they’ve balanced safety concerns with Second Amendment arguments over individuals’ right to bear arms.

But a U.S. Supreme Court decision last year could upend the new law and other gun restrictions elsewhere, legal scholars say.

In that ruling, justices said lower-court judges no longer can decide on the constitutionality of gun laws on the basis of modern concerns about public safety.

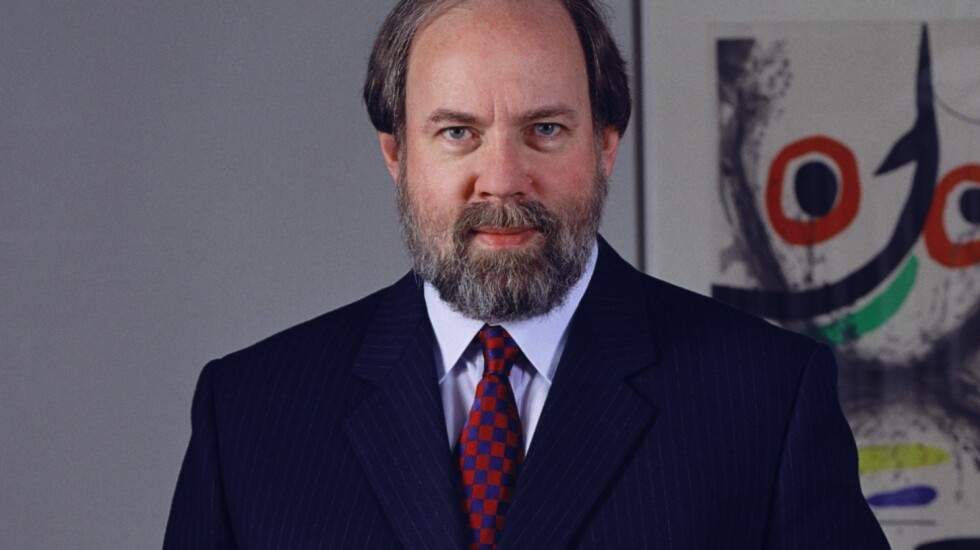

“The Supreme Court has completely transformed the way Second Amendment cases get litigated,” said Eric Ruben, a Southern Methodist University assistant law professor who focuses on gun issues.

Illinois is the ninth state to have passed a law banning assault weapons.

Legal challenges to bans in California and Maryland are pending before federal appeals courts and would be the most likely ones to be heard by the Supreme Court, according to Andrew Willinger, executive director of the Duke Center for Firearms Law.

Willinger said he thinks a Supreme Court vote on the constitutionality of assault weapons bans would be “a close one.”

“It seems highly likely there would be justices inclined to strike down” an assault weapons ban, Ruben said. “Whether there are five” — the number needed for the necessary majority — “is another question.”

In a Jan. 6 story in The Washington Post, Adam Winkler, a professor at the University of California at Los Angeles School of Law, said, “There’s at least a decent chance that the [Illinois] law will be struck down.

The recent Supreme Court decision that changed the landscape on the Second Amendment is known as New York State Rifle & Pistol Association, Inc. v. Bruen. The high court’s 6-3 ruling in that case last June 23 said judges must rely on the Second Amendment’s text and the history of gun regulation to decide the constitutionality of gun laws — and not on the strength of the public safety purpose of those laws.

The decision overturned New York ‘s restrictions on concealed-carry gun permits.

In the majority opinion, conservative Justice Clarence Thomas wrote: “Reliance on history to inform the meaning of constitutional text is more legitimate, and more administrable, than asking judges to ‘make difficult empirical judgments’ about ‘the costs and benefits of firearms restrictions.’”

In support of that stance, Thomas referred to the Supreme Court’s 2008 decision in a case known as District of Columbia v. Heller, which found that the Second Amendment guarantees the right to “possess and carry arms in case of a confrontation.” That ruling struck down a ban on handguns in Washington, D.C.

The Heller decision said guns in “common use at the time” are constitutionally protected, but it preserved the “historical tradition of prohibiting the carrying of ‘dangerous and unusual’ weapons.”

It also said the right to bear arms isn’t unlimited. The government, for instance, can ban felons from possessing firearms and forbid them in government buildings and schools, the ruling said.

Because of the Heller and Bruen decisions, Willinger said a key question in any challenge to an assault weapons ban will now be whether those firearms are “dangerous and unusual” or “in common use.”

“Currently, there is a lot of confusion” about how to litigate gun cases in light of the Bruen ruling, Ruben said.

In 2015 — seven years after the Heller decision and seven years before Bruen — Highland Park’s ban on assault weapons was upheld by the Seventh U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, but that case didn’t make it to the Supreme Court.

Public safety concerns — which no longer can be considered in courts’ gun rulings because of the Bruen decision — were central to the decision by federal appellate Judge Frank Easterbrook to uphold the Highland Park ban.

“A ban on assault weapons won’t eliminate gun violence in Highland Park, but it may reduce the overall dangerousness of crime that does occur,” Easterbrook wrote. “If a ban on semiautomatic guns and large-capacity magazines reduces the perceived risk from a mass shooting and makes the public feel safer as a result, that’s a substantial benefit.”

Easterbrook also wrote: “Highland Park concedes uncertainty whether the banned weapons are commonly owned. If they are (or were before it enacted the ordinance), then they are not unusual. The record shows that perhaps 9% of the nation’s firearms owners have assault weapons, but what line separates ‘common’ from ‘uncommon’ ownership is something the [lower] court did not say.”

In addition to banning assault weapons, the new Illinois law caps the capacity of magazines at 10 rounds for long guns and 15 for handguns.

Ruben said other states also have bans on magazine capacity — and some of those laws are under court scrutiny.

Shortly after the Bruen decision, the Supreme Court vacated lower-court decisions that upheld bans on high-capacity magazines in New Jersey and California. Those cases were sent back to the judges in those cases to reconsider their rulings in light of Bruen.

The legislators who sponsored the Illinois assault weapons ban say they’re confident it will survive.

“The constitutional interpretation of the Second Amendment, of course, loomed large in the drafting of this legislation,” state Rep. Bob Morgan, D-Deerfield, said at Gov. J.B. Pritzker’s bill-signing ceremony Tuesday night.

“Both chambers took that very seriously,” Morgan said. “We have to make sure that we’re passing laws that will withstand scrutiny. So we took those things into account. And, of course, there are a lot of legal threats that came, and we look forward to being able to take our arguments to court.”

State Sen. Terry Bryant, R-Murphysboro, opposed the legislation.

“I believe the courts will be looking at it and saying that’s something that regular citizens can have,” he said.

State Sen. Chapin Rose, R-Mahomet, said, “If you read the applicable U.S. Supreme Court case law, I have every confidence that this will get thrown out very quickly in federal court as well.”

In a written statement, Richard Pearson, executive director of the Illinois State Rifle Association, said his group will work to get the assault weapons ban repealed in the next session of the General Assembly “as well as consider litigation on what many believe is a constitutionally flawed bill.”

In a December appearance before an Illinois House panel considering what was then the proposed assault weapons ban, former National Rifle Association lobbyist Todd Vandermyde said: “You guys pass whatever garbage you want, and we’ll see you in court.”

He said he didn’t think many law enforcement agencies would enforce the ban.

On Wednesday, 14 of the 102 sheriffs in Illinois, including those in Kankakee, Grundy and McHenry counties, posted messages on social media saying they wouldn’t arrest citizens for violating the ban.

“I would assume that someone soon will be filing a suit against the state of Illinois, alleging that this law violates the 2nd amendment of the U.S. Constitution, similar to the passage of the Safe-T Act, and it will be sent to the Supreme Court to decide on the constitutionality of the new law,” Greene County Sheriff Robert McMillen wrote.

“Until that happens, and the constitutionality issue is decided, I am going to follow my morals, beliefs and obligations concerning protecting the rights of Greene County’s citizens,” McMillen said.

Ruben said there has been a similar response elsewhere. When New York banned assault weapons in 2013, sheriffs staged a revolt against that law, he said.

“The constitutionality is one thing,” Ruben said. “Law enforcement, in many ways, is going to be an even bigger issue here.”