Protections against banking fraud in the U.S. have never been able to keep pace with criminals.

The reason why has its roots in the start of the national banking system proposed by Abraham Lincoln and created by Congress in 1863.

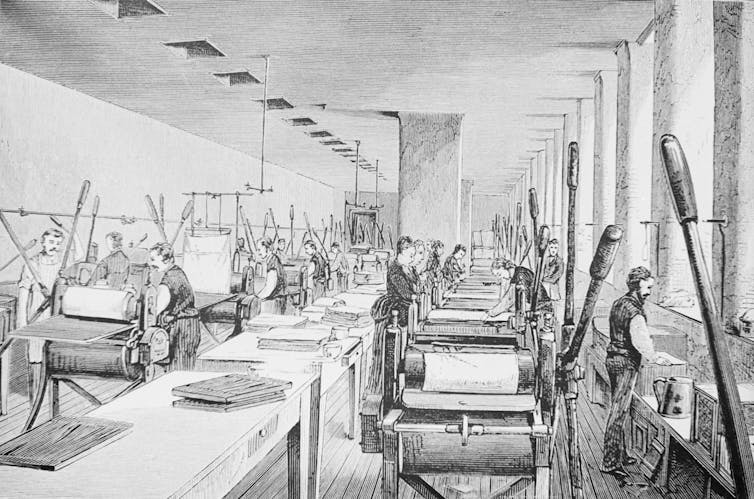

Until the mid-Civil War, the U.S. didn’t have its own federal currency. Banks were free to create their own paper money, subject only to state law, which varied dramatically. One-third of all paper money circulating before the Civil War was likely counterfeit, resulting in currency mayhem.

Lincoln’s goal was to create the nation’s first federal paper currency – national bank notes that only newly approved national banks could issue, subject to regulation by the United States’ first financial regulator, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency.

To secure the new federal currency, these national banks were required to purchase interest-bearing U.S. government bonds from the U.S. Treasury.

This financed the Union Army, but it accidentally created a dual banking system. At the time, the wartime Congress thought state-chartered banks would go away, choosing to become national banks that could issue federal currency.

Congress was wrong.

The ensuing dual banking system, with no single regulator in charge of policing all banks, still exists today.

State banks couldn’t issue the new federal currency. Soon, Congress enacted a federal tax on state bank paper currency in an attempt to drive state banks out of business.

To stay in business, state banks needed to issue new financial products. The first one, which came during the Civil War, was what eventually became known as the check.

Since then, state and federal regulators have competed to find ways to earn different streams of income.

Again and again, as criminals began finding ways to defraud banks, Congress and regulators addressed the complaints, but piecemeal. And in this game of regulatory “whack-a-mole,” banks attempted to stay at least one step ahead.

A ‘race to the bottom’

In 2009, then-Senate Banking Committee Chair Christopher Dodd called banking regulation a “race to the bottom.”

When credit card abuses came to light, Congress amended the Truth in Lending Act, causing the Federal Reserve to change Regulation Z, which protects consumers from unfair lending practices. The adjustment required banks to provide refunds for transactions that credit card holders hadn’t authorized. This led to losses to banks’ bottom lines.

Banks then created debit cards. When consumers began to lose money through debit card fraud, Congress passed amendments to the Electronic Fund Transfer Act, causing the Fed to adjust Regulation E, which protects consumers from unauthorized or incorrect electronic fund transfers. This adjustment added similar consumer protections for fraudulent debit card transactions.

But by then, the industry was moving to a new payment innovation – gift cards, served up without the fraud protections for consumers offered by debit and credit cards, even though many of those gift cards have the word “debit” printed on them.

Today, regulators and Congress are still trying to catch up to the fraudsters.

Read The Conversation’s investigation into gift card fraud here: Gift card scams generate billions for fraudsters and industry as regulators fail to protect consumers − and how one 83-year-old fell into the ‘fear bubble’

Dr. David P. Weber receives funding from the Administration for Community Living (ACL), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to combat elder financial and high tech exploitation on the Eastern Shore of the Chesapeake Bay, Maryland. The award totals $2.6 million of financial assistance, with 80 percent funded by ACL/HHS and 20 percent funded by Maryland state and local government sources. The contents of this investigative story are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by ACL/HHS, or the U.S. Government.

Jake Bernstein does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.