If you look at the paws of a cat, a dog or even a kangaroo, you'll notice they have something in common with our hands. Even if some might be shrunken or differently positioned, all of these mammals have five digits, or fingers. Why do we share this pattern with our furry friends, even though we evolved under different conditions?

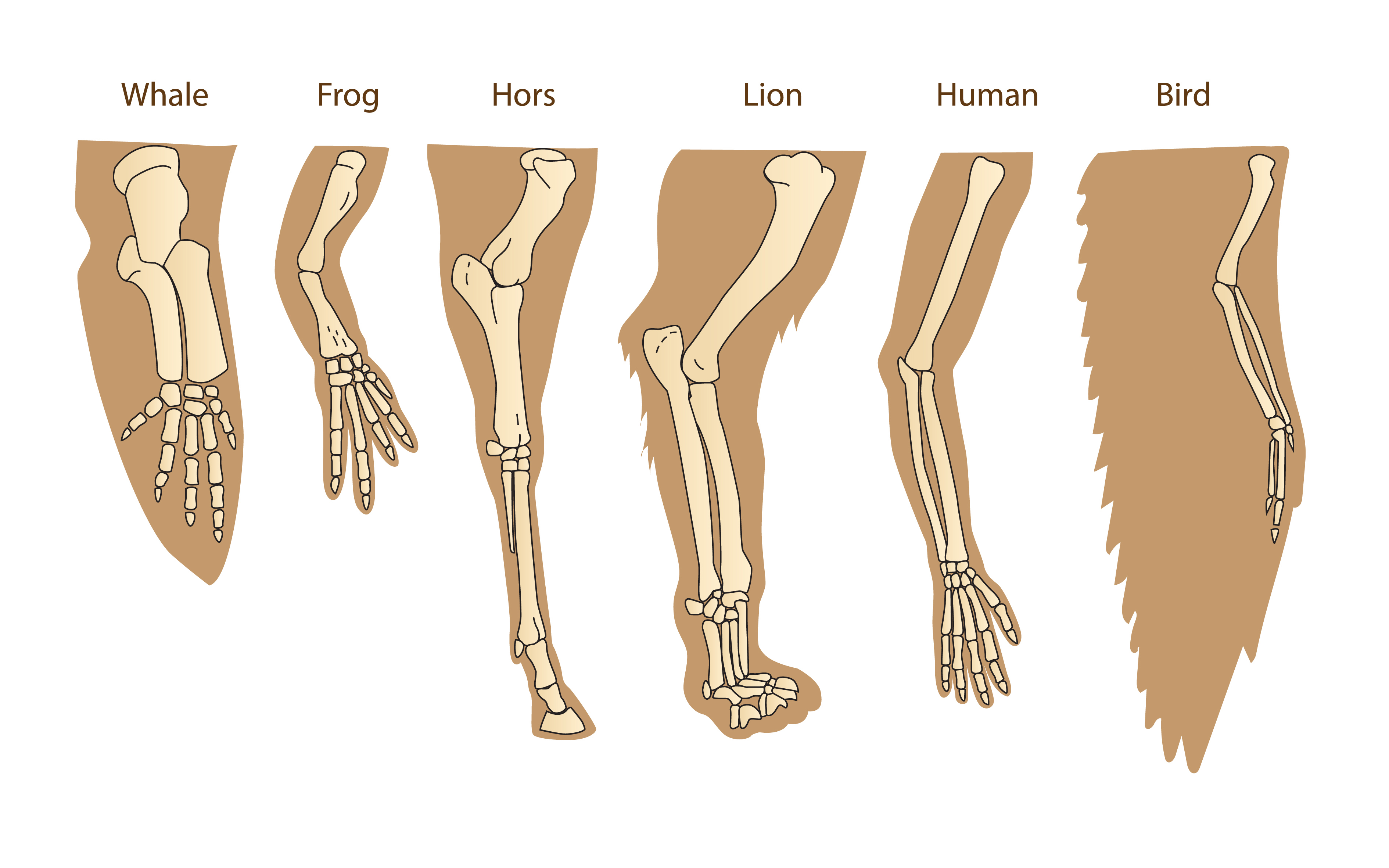

To answer the question of why mammals have five fingers, we must first understand why tetrapod (Greek for "four-footed") vertebrates have five fingers. Mammals belong to the superclass Tetrapoda, which also includes reptiles, amphibians and birds. Even members of this group without traditional limbs have five fingers in their skeleton — whales, seals and sea lions have five fingers in their flippers — even if they have four or fewer toes.

There is some variation: Horses have just one toe, and birds have one fused finger bone at the end of their wing. However, scientists have discovered that these animals start out with as many as five fingers as embryos, but they shrink away before they are born.

This process is dictated largely by Hox genes, Thomas Stewart, an evolutionary biologist at Penn State, told Live Science. Hox genes encode proteins that help regulate the activity of other genes, turning them on or off. They help ensure that body parts end up in their correct location in an animal's body, as it develops from an embryo. As such, they're involved in dictating the skeletal pattern of tetrapods and do so by helping to control proteins created by the sonic hedgehog gene (yes, that's the real name) to activate and block each other while creating tissues.

Through this process, finger buds grow; depending on the type of animal, these buds could either continue growing or reabsorb. Then, the cells around where the fingers should be die, creating separate digits. Exactly how this happens is "admittedly a pretty complicated problem," Stewart said. The details vary depending on which scientist you ask.

Nobody is sure when this five-finger plan first evolved. The first known animals to develop fingers evolved from fish around 360 million years ago and had as many as eight fingers, Stewart said. However, the existence of the five-finger plan in most living tetrapods indicates that the trait is likely a "homology" — a gene or structure that is shared between organisms because they have a common ancestor. The common ancestor of all living tetrapods must have somehow evolved to have five fingers and passed that pattern down to its descendants.

A common ancestor explains how mammals got five fingers, but it doesn't tell us why. One theory is canalization — the idea that over time, a gene or trait becomes more stable and less likely to mutate. Stewart gave the example of cervical, or neck, vertebrae: Mammals almost always have seven of these vertebrae even though that number doesn't seem to offer a particular advantage. If the number has worked for millions of years, there's no reason to change it, according to this theory.

Related: Which animal species has existed the longest?

However, not all researchers agree with the canalization idea. Kimberly Cooper, a evolutionary developmental geneticist at the University of California, San Diego, points out that polydactyly, or having more than five fingers, occurs as a mutation in many mammals, including humans. There are multiple mutations that can cause polydactyly, but a recent study published in the journal Nature found that it can happen through the mutation of just one nucleotide in the sonic hedgehog gene.

"If it's that easy," Cooper asked, "why don't polydactyl species exist?" She argued it must be because polydactyly is an evolutionary disadvantage. Some speculate it might be down to gene linkage: As genes evolve over millions of years, some become linked, meaning changing one gene (the amount of fingers) could lead to other more serious health issues. But as of yet, nobody has offered concrete proof, Stewart told Live Science.

"We can ask a very simple question of why don't we see more than five fingers, and it seems like we should arrive at a simple answer," he said. "But it's a really deep problem. That makes [this field] really exciting."