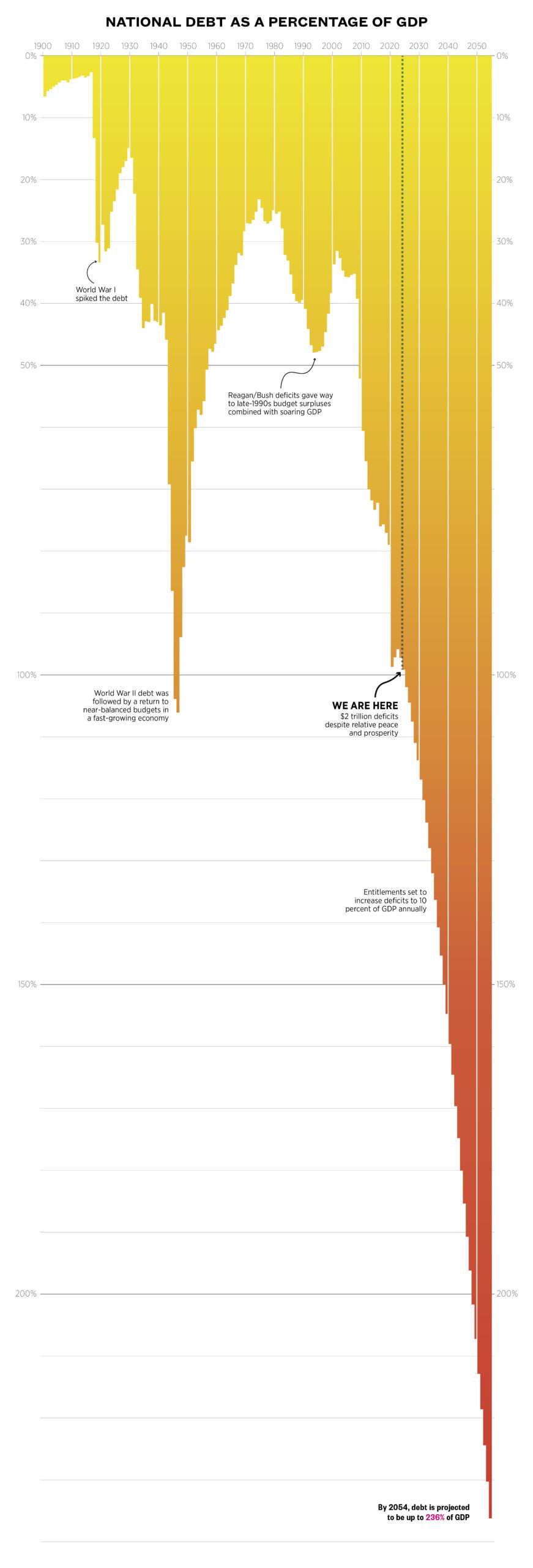

Scroll down to see how big the national debt may get over the next few decades, and then read about how we got here.

When President Joe Biden delivered his 2023 State of the Union address, Washington was drowning in a sea of red ink. The annual budget deficit was in the process of doubling from $1 trillion to $2 trillion in a single year due to some student-debt cancellation shenanigans. That year's budget deficit would become the largest share of gross domestic product (GDP) in American history outside of wars and recessions. Economists at the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and across the political spectrum warned that continuing to ignore the escalating Social Security and Medicare shortfalls while also opposing new broad-based taxes was unsustainable and could bring a painful debt crisis.

How did the nation's highest elected officials respond to this economic challenge? Biden promised that "if anyone tries to cut Social Security [or] Medicare, I'll stop them. I'll veto it." He also accused congressional Republicans of plotting to reform these programs—prompting outraged shouts from Republicans who resented the accusation of caring about the looming insolvency of the Social Security and Medicare trust funds. When the president triumphantly taunted that such boos reveal a new bipartisan consensus to do nothing about Social Security and Medicare shortfalls, both Republicans and Democrats leaped to their feet with thunderous cheers. For good measure, both parties endorsed Biden's prohibition on any new taxes for 95 percent of families. Washington's dangerous borrowing spree would continue with enthusiastic bipartisan support.

Paradoxically, the faster government debt escalates toward an inevitable debt crisis, the less politicians and voters seem to care. In the 1980s and 1990s, more modest deficits dominated economic policy debates and prompted six major deficit reduction deals that balanced the budget from 1998 through 2001. That era is long gone. In the past eight years, President Donald Trump and then Biden enacted $12 trillion in deficit-expanding legislation even as Social Security and Medicare shortfalls drove baseline deficits higher. When even liberal economists warned politicians that the post-pandemic economy faced a modest degree of rising inflation and interest rates—and that a federal spending spree would pour gasoline on that fire—lawmakers responded by enacting the $2 trillion American Rescue Plan. When inflation and mortgage rates resultantly surged to 9.1 percent and 7.8 percent, respectively, lawmakers brazenly continued the inflationary spending spree.

Why are we no longer responding to soaring debt and its economic consequences? While there are many factors, the three most important are these: 1) We've convinced ourselves that deficits do not matter; 2) partisan politics and the collapse of lawmaking have turned deficits into a weapon to be politicized rather than a problem to be solved; and 3) few of us are willing to face the unpopular reality that this issue cannot be resolved without fundamentally reforming Social Security, Medicare, and middle-class taxes.

Debt Drivers

Few voters, or even politicians, have fully grasped how perilous Washington's fiscal outlook has become. While budget deficits have historically averaged 3 percent of GDP—ensuring the debt grows no faster than the overall economy—the deficit reached 7.5 percent of GDP last year and is projected to swell to 14 percent of GDP over three decades if current tax and spending policies are extended. If the federal debt continues to roll over into the 4.5 percent interest rate seen at recent Treasury debt auctions, then the budget deficit may surpass $4 trillion within a decade.

When a debt becomes this enormous, interest rates become a budgetary time bomb. Even if rates stay below 4 percent forever—as the CBO's projections questionably assume—projected interest costs will consume a quarter of all federal taxes within a decade and become the largest annual federal expenditure within two decades. If rates rise, each percentage point will add $35 trillion in interest over three decades—the cost of adding another Defense Department. Again, that's for each percentage point.

To many economists, the most important debt figure is the total federal debt as a share of the economy. This "debt ratio" has already leapt from 40 percent to 100 percent since 2008, and it is projected to exceed 230 percent within three decades under current policies. If interest rates gradually rise to 5 percent or even 6 percent, the debt ratio could surpass 300 percent, with interest costs consuming nearly all annual tax revenues. There would be no tax revenues left to finance any federal programs.

If this sounds unduly alarmist, consider that the economists at the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School could not even project a functioning long-term economy on our current debt path. The economists write that their economic models "effectively crash when trying to project future macroeconomic variables under current fiscal policy. The reason is that current fiscal policy is not sustainable and forward-looking financial markets know it."

The driver of this debt is no mystery. The combination of rising health care costs and 74 million retiring baby boomers is driving annual Social Security and Medicare costs far above their payroll tax and Medicare premium revenues. These annual program shortfalls—which must be funded with general tax revenues and new borrowing—will exceed $650 billion this year on their way to $2.2 trillion annually a decade from now, when including the interest costs of their deficits. Specifically, by 2034 Social Security and Medicare will be collecting $2.6 trillion annually in revenues while costing $4.8 trillion in benefits and associated interest costs.

And that's just the beginning. Over 30 years, CBO data show Social Security and Medicare facing an annual shortfall of $124 trillion while the rest of the budget is roughly balanced. By 2054, these two programs will be contributing 11.3 percent of GDP to annual budget deficits, or the current equivalent of $3.2 trillion in annual program shortfalls (including the interest costs of their deficits). As for the rest of the budget, CBO projects that tax revenues will continue to rise, and other program spending to fall, as a share of the economy. This means the entire long-term deficit growth is driven by Social Security, Medicare, and the interest cost of their shortfalls.

Baby boomer retirements, health care costs, and rising interest rates combine to create what Bill Clinton's former White House chief of staff, Erskine Bowles, in 2012 called "the most predictable economic crisis in history." As far back as the 1990s, experts warned that surging retirements in the 2010s and 2020s would push Social Security and Medicare costs dangerously far above their more-steady payroll tax revenues. Yet attempts in the 1990s and early 2000s to gradually phase in reforms while the boomers were still young enough to adjust to them went nowhere. Consequently, stabilizing the debt will now entail deeper and more drastic Social Security and Medicare reforms—as well as increases in middle-class taxes—that can no longer exempt current and near retirees.

We cannot grandfather out of reform the 74 million boomers whose costs are driving the $124 trillion shortfall. Nor can we tweak our way out of this. If the system is to be kept afloat, Social Security's eligibility age must rise, its benefit growth formulas must be significantly curtailed for above-average earners, and its taxes may need to rise too. Medicare premiums must steeply rise for above-average earners, and its elevated costs addressed either with a new choice- and competition-based premium support system or with ambitious price and payment reforms to scale back costly procedures.

Washington will not even discuss this.

Deficits Do Matter

Younger voters may not grasp how much deficit concerns dominated economic policy debates from 1982 through the end of the century. As deficits widened under President Ronald Reagan, due to tax cuts and military spending, deficit reduction became a top voter priority, driven by concerns of elevated interest rates, sluggish economic growth, and foreign debt ownership. These deficit concerns—colored by a modest recession—helped elect President Bill Clinton in 1992. In The Agenda, Bob Woodward detailed the Clinton White House's monomaniacal focus on budget deficits, interest rates, and the bond market when pushing its 1993 tax hike bill. Even with the debt roughly stable as a share of the economy, both parties demanded aggressive deficit reduction to cut interest rates, spur investment, and encourage economic growth.

After six major deficit reduction deals and a temporary revenue surge finally brought balanced budgets from 1998 through 2001, triumphant lawmakers shifted the debate to how to spend $5 trillion in projected (and, in retrospect, fake) 10-year surpluses. Even as a sluggish economy eliminated those surpluses, Washington's appetite for replacing austerity with tax cuts, war spending, and new entitlements could not be stopped. Vice President Dick Cheney famously declared "deficits don't matter"—and when Great Recession stimulus spending brought the first trillion-dollar deficits without any immediately apparent danger, all of Washington wanted to join the party. Low interest rates made federal borrowing cheap, and the 2016 and 2020 presidential campaigns saw Sen. Bernie Sanders (I–Vt.) propose between $60 trillion and $97 trillion in new spending over a decade. Then Presidents Trump and Biden enacted $12 trillion in deficit-financed legislation in just eight years.

Progressives even invented an absurd justification for enormous deficits. Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) inexplicably claimed that Scandinavian-size spending could be financed by radically expanding the money supply without significant inflation. The 72 leading economists on the left and right responding to an expert survey unanimously rejected the MMT's ahistorical and nonsensical claims. The MMT's real purpose was to concoct an economic justification for progressives' longstanding desire to drastically expand government unconstrained from the limits of plausible taxation.

In hindsight, the economy managed the post-2000 debt surge because the initial 32 percent of GDP debt level provided some fiscal space for additional borrowing. Furthermore, the sluggish economy, an accommodating Federal Reserve, and a global savings glut drove a historic interest rate decline that made debt more affordable for families, businesses, and the federal budget.

That free-lunch era is now over. The federal debt exceeds 100 percent of GDP and is set to double or even triple over a few decades. These debt levels are rendered even more unaffordable by rising interest rates, as the structural factors that long reduced rates begin to reverse. Consensus economic analysis suggests that the debt surge itself will elevate interest rates by as much as three percentage points.

Unfortunately, American politics has not caught up to this new economic reality—which brings us to one of the biggest barriers to reform.

Partisan Politics and the Collapse of Lawmaking

Washington was not always as hyperpartisan and dysfunctional as it is today. In 2019, I analyzed the 14 leading "grand deal" deficit negotiations from 1983 through 2019 to learn why six negotiations successfully enacted legislation and eight failed. The most important cause of the recent failures, I found, has been Congress itself.

Up through the mid-1990s, Republicans and Democrats—despite public bickering—often collaborated well behind the scenes. During the 1983 Social Security negotiations to avert a looming trust-fund insolvency, Reagan and House Speaker Tip O'Neill (D–Mass.) pledged not to attack each other's approaches in public. President George H.W. Bush and congressional Democrats trusted each other in the 1990 budget deal negotiations that brought new spending controls and tax increases. Even the 1997 balanced budget agreement between Clinton and House Speaker Newt Gingrich (R–Ga.), coming two years after a rancorous government shutdown, was a model of healthy, trustworthy, bipartisan negotiations.

This bipartisan era ended abruptly in January 1998, when the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal broke. Clinton and Gingrich canceled a bipartisan fix to Social Security that was set to be announced just days later. Deficit concerns did not return until 2009, and by then Washington was far more polarized.

Rather than stay in D.C. during the legislative session and build bipartisan relationships—which voters once rewarded—lawmakers now fly into Washington on Monday evening, attack the other party in press releases and floor speeches, and then fly out on Thursday afternoon. The media landscape has become fragmented, partisan, paranoid, and obsessed with narratives of betrayal. Gerrymandered House districts leave members more fearful of primary challenges from true-believing partisans than of losing swing voters in the general election. Most congressional policy making has been removed from relatively bipartisan congressional committees and centralized in the Capitol offices of the House and Senate party leaders.

The result is 24/7 partisan warfare, with individual issues seen as little more than interchangeable weapons in the day's communication wars. For the past two years, Republicans and Democrats savaged each other over inflation—the voters' top issue—without either side bothering to offer serious legislation to solve the problem. (The cynically named "Inflation Reduction Act" had little to do with combating inflation.) In this environment, neither party dares to push politically risky entitlement reforms or broad-based taxes. Just ask former House Speaker Paul Ryan (R–Wisc.), whose earlier efforts earned him bipartisan hatred from voters and an attack ad portraying him murdering a senior citizen.

Even if the parties could trust each other to negotiate a good-faith deficit deal, their own purity-test voters would accuse them of surrendering to the other side. So Republicans and Democrats just point fingers at each other. Deficits are not a problem to be solved, but instead another weapon in the partisan communications war.

No More Easy Solutions

In the 1980s and '90s, lawmakers could tweak their way to deficit reduction. Nearly half of federal spending was discretionary, and the Cold War victory brought vast military savings that minimized the need for austerity elsewhere. A late-1990s revenue bubble was enough to bump the deficit into surplus for four years. The political payoff of a balanced budget was worth these modest reforms.

Today's deficits of $2 trillion—headed toward $3 trillion or even $4 trillion—cannot be tweaked away. Balancing the budget is virtually impossible, and even stabilizing the long-term debt at today's 100 percent of GDP requires wildly unpopular changes to Social Security and Medicare (and will likely take broad-based taxes). Other reforms are necessary but far from sufficient.

Yet Washington refuses to confront this budget math, relying instead on publicity stunts. Voters search for "one cool trick" that would quickly and painlessly balance the budget if only the out-of-touch politicians would listen.

Start with Republicans. The GOP canon begins by asserting that deficits are always driven by Democratic spending. This narrative is flatly contradicted by Presidents George W. Bush and Trump, both of whom expanded federal spending by trillions of dollars while enacting trillion-dollar tax cuts. The last time Republicans controlled both the White House and Congress, in 2017 and 2018, they immediately cut taxes by $1.5 trillion, expanded discretionary spending by 13 percent in one year, and rejected all entitlement savings.

"But those tax cuts paid for themselves," Republicans retort, which incorrectly assumes that pre-cut tax rates are always above the Laffer Curve's revenue-maximizing rate. This math also requires that every tax cut dollar adds at least $5 in economic output, taxed at an average 20 percent rate to recover that lost revenue dollar. While tax cutters will point to rising tax revenues as evidence of "free" tax cuts, even a stable tax code will produce rising revenues due to inflation, population growth, rising real wages, and business profits. Despite the many positive attributes of GOP tax cuts, they undeniably resulted in lower tax revenues than otherwise.

On the spending side, Republican voters are quick to claim that a $2 trillion deficit can be mostly eliminated by cutting foreign aid (just 1 percent of federal spending) or the classic "waste, fraud, and abuse," as if such a line-item exists in the federal budget to be zeroed out. Some Republicans like to talk about eviscerating social spending, but that rhetoric tends to fall apart when you calculate how much of that spending you'd need to cut to meet the GOP's balanced-budget targets: You'd need to eliminate all funding for veterans' benefits, child credit payments, the earned income tax credit, school lunches, disability benefits, K-12 schooling, health research, unemployment benefits, food stamps, homeland security, infrastructure, embassy security, federal prisons, border security, and much more. There is not much Republican appetite for that. (And no, immigration does not significantly widen federal budget deficits, although it can raise state and local government costs.)

GOP leaders also rely on gimmicks. Trump absurdly promises to pay off the $27 trillion federal debt with oil and gas revenues. One recent Republican presidential candidate, Vivek Ramaswamy, promised to grow the economy to a balanced budget. That lazy contention not only requires nearly impossible growth rates; it fails to acknowledge that faster economic growth also raises Social Security and Medicare costs and interest rates on the federal debt.

Without a consensus around a serious deficit reduction agenda, many Republicans rely instead on gimmicks and publicity stunts. So-called government shutdowns affect less than a tenth of federal spending, eviscerate many of the most popular programs, and guarantee an intense voter backlash. Similarly, debt limit showdowns offend voters as a crude way of eliminating an undetermined quarter of federal spending, defaulting on federal contract payments, and potentially defaulting on the debt with devastating economic consequences. They never succeed.

Another Republican gimmick is simply to demand a balanced budget amendment, or easy-sounding spending caps such as the "Penny Plan," without specifying how to meet their impossibly tight savings targets. Empty lawmaker pledges to quickly balance the budget while also extending the 2017 tax cuts and protecting key spending priorities—a mathematical and political impossibility—are meant to distract conservative voters from their runaway spending. Talk like Barry Goldwater; spend like LBJ.

So George W. Bush signed legislation collectively adding $6.9 trillion in debt, while Trump signed $7.8 trillion in just four years. The House GOP's balanced budget plan consists nearly entirely of gimmicks. Lawmakers engage in symbolic fights over small slivers of discretionary social spending while entitlement costs skyrocket. Freedom Caucus lawmakers give angry press conferences demanding colossal spending cuts without bothering to lay out any specific savings blueprint to meet their demands—or doing the necessary outreach, negotiating, and coalition building to win over skeptical lawmakers. It's all just a show; performative outrage for gullible voters.

Democrats have also built their own bubble of misinformation and excuses. The most basic progressive narrative claims that deficits do not matter and are merely a green-eyeshade scheme to serve the wealthy over the people. These progressives offer no answer for who will lend Washington at least $120 trillion over 30 years, or how such debt will affect the economy. The MMT enthusiasts call for financing such deficits with new money creation and then pretend hyperinflation would not result. "Zombie Keynesians" assert that trillions of dollars in deficit spending is needed to keep the economy afloat, and that even slowing the growth of spending would bring recession, mass poverty, and social collapse. (Real Keynesians acknowledge that recessionary stimulus also requires offsetting austerity during economic expansions.)

Liberal Democrats suddenly become anti-deficit when hammering Republicans. Flipping the GOP argument, they assert that Republicans drive the debt because deficits expanded during recent Republican presidencies and declined under Democrats. Yet such arguments measure only the first and last years of each presidency, which are often heavily affected by one- to two-year fiscal anomalies outside of presidential control, such as the 2000 revenue bubble, the 2008 housing crash, and the 2020 global pandemic. In fact, the partisan effect on deficits disappears if you measure deficits across entire presidencies, control for factors that are inherited or outside presidential control, and incorporate the partisan makeup of Congress passing the budget bills. Unfortunately, these standard economic and statistical cleanups do not fit in a meme.

Perhaps the most persistent Democratic myth is that tax cuts for the wealthy caused today's deficits and that taxing the rich can eliminate the problem. The math just doesn't back this up. Annual federal budgets since 2000 have fallen from a 2.3 percent of GDP budget surplus to a 7.5 percent of GDP deficit. That 9.8 percent decline results from annual spending jumping 6.3 percent of GDP; the bursting of the 2000 revenue bubble, which reduced revenues by 1.5 percent of GDP; and tax cuts, costing 2 percent of GDP. Approximately 70 percent of the 2001 and 2017 tax cut costs (and subsequent extensions) went to earners in the middle and lower classes. Out of that 9.8 percent of GDP fiscal decline, that leaves just 0.6 percent that can be attributed to "tax cuts for the rich."

So how do critics claim that "tax cuts for the rich" drive deficits? By including all tax cuts even for the nonwealthy. Or simply giving a free pass to the 5.5 percent of GDP entitlement spending hike since 2000 and then blaming tax revenues for not keeping up.

In its more extreme form, this fiscal fallacy insists that simply taxing the rich can not only close between $120 trillion and $150 trillion (depending on current policy extensions) in total budget deficits over three decades, but also finance a full Nordic social democracy. The first problem with this claim is mathematical. Even seizing every dollar of wealth from America's 800 billionaires—every home, yacht, business, and investment—would merely fund the federal government for nine months. And then the money would be gone. So would your 401(k), given that most of this wealth would be seized from the stock market. Not even the Sanders fantasyland tax agenda of a 77 percent estate tax, 8 percent wealth tax, and huge corporate, income, and investment taxes could finance Washington's current spending promises, much less his enormous new spending agenda. There simply are not enough millionaires, billionaires, and undertaxed corporations to close a minimum $120 trillion shortfall or finance a generous social democracy for 330 million Americans.

The second problem is economic. Only so many upper-income taxes can be layered on top of each other before surpassing their revenue-maximizing rates. At most, 1 percent to 2 percent of GDP in new taxes could be raised from high earners and corporations before their tax rates reach revenue-maximizing levels and the economy begins to capsize.

The final problem is political. Even a unified, unconstrained Democratic government in 2021 and 2022 limited its tax-the-rich reach to a modest and exception-stuffed corporate minimum tax and some IRS funding. It turns out that a lot of high earners and corporations are located in California and New York, where they help elect Democratic congressional leaders, who are not eager to bury them in a socialist tax revolution.

Progressive lawmakers exaggerate tax-the-rich savings by recycling the same few tax proposals to pay for countless spending proposals. Liberals lionize the 91 percent income tax rates of the 1950s, without doing the basic research to discover that: 1) Virtually no one in those days actually paid marginal tax rates over 50 percent; 2) those high earners paid lower effective rates than today; and therefore 3) the high tax rates of the 1950s to 1970s collected a smaller share of GDP in revenues than the post-1980 era of significantly lower tax rates. And when tax-the-rich progressives call for matching Europe's higher tax revenues, they ignore the fact that virtually all of Europe's revenue advantage results from broad-based value-added and payroll taxes, not additional upper-income taxes. Taxing the rich should be on the table—as should all savings policies—but cannot close more than a modest fraction of the shortfalls.

Democrats offer other dubious easy solutions to deficits. The popular target of Pentagon spending has already fallen from 6 percent to 3 percent of GDP since the 1980s and is projected to continue declining to 2.5 percent, which is not far above NATO's 2 percent target. Moreover, congressional calls to dramatically slash military spending have not been backed up by specific proposals, because even progressive lawmakers cannot figure out how to meet their savings targets.

Similarly, Medicare for All is more of a talking point than a serious savings proposal. Bills from Sanders and Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D–Wash.) promise nearly impossible efficiency savings yet fail to specify any new provider payment system to achieve them. Instead, the bills lamely assign someone else to figure out how to make it all work. Meanwhile, economists estimate that any modest efficiency savings would be spent on expanded benefits, leaving national health expenditures largely unchanged. Additionally, no one has yet designed a "Medicare for All" tax large enough to replace the $3 trillion in annual private health spending that would be nationalized. Most crucially, none of these proposals would affect Medicare's projected $87 trillion three-decade shortfall, because, obviously, old-age Medicare already pays Medicare for All's lower provider rates.

Some myths are bipartisan, such as claiming that Social Security and Medicare cannot legally run deficits, that most seniors are impoverished, and that retirees collect only as much as they paid into the systems. In reality, those two programs will run a combined deficit of $650 billion this year, senior incomes have soared four times as fast as worker incomes since 1980, and most retirees receive Social Security and especially Medicare benefits substantially exceeding their lifetime contributions.

Another myth is that the Social Security trust fund contains real resources to pay benefits—or would have if politicians had not "raided it" for other spending. Some claim that long-term Social Security and Medicare projections are just guesses, even though their retirees already exist with benefit formulas set in law; or that we can shield everyone over age 50 from reform, even though that window closed 20 years ago.

The media often encourage fake solutions and deficit denial. Bloomberg has hyped the mathematically impossible free-lunch fantasy that billionaire taxes can fix Social Security. Not surprisingly, it proved popular. Leading media organizations criticize runaway deficits but then respond to even modest proposed spending cuts with apocalyptic coverage of families who supposedly will be driven into destitution if their Social Security benefits grow at a slightly reduced rate or their Medicare co-pays rise by a few dollars.

Back to Reality

Our fiscal lies and myths reflect motivated reasoning because we refuse to confront the inevitable tradeoffs for Social Security, Medicare, and middle-class taxes. I have briefed dozens of lawmakers and some top presidential candidates. They are aware that the untenable fiscal situation is heading toward a painful reckoning. But most simply refuse to discuss it publicly—and some even demagogue political opponents who try to address it—because they admit that the brutal politics of deficit reduction leave them no choice.

And for that, the voters are to blame. We oppose real deficit reforms in favor of "one cool trick" gimmicks. We make self-righteous fiscal demands that are incoherent, contradictory, and reckless, such as simultaneously calling for a balanced budget, higher spending, and no more taxes. We vote for Santa Claus candidates of both parties who promise a free lunch and reject candidates who acknowledge fiscal tradeoffs. We blame the other party for deficits and savage any politician who dares to propose real reforms. Ultimately, we are the reason that admittedly craven politicians won't risk addressing our looming fiscal insolvency. And we will eventually pay the price.

It's time for voters and politicians to confront some inconvenient truths. Washington has promised substantially more spending than the economy and tax system will be able to deliver. There is no easy solution that everyone missed or that politicians are hiding from you. Washington cannot continue its current course toward a debt of 200 percent or even 300 percent of the economy. The financial markets will surely not be able to lend us between $120 trillion and $150 trillion over three decades at interest rates of just 2 percent or 3 percent. We do not know precisely when the financial markets will tap out and demand unaffordable interest rates, creating a vicious circle of rising debt and interest rates. But that day will almost certainly arrive unless Congress acts.

Here's the painful reality for Republicans: You cannot stabilize the long-term debt with tax revenues remaining at 18 percent of GDP. Federal spending is headed toward 32 percent of GDP, due to 74 million baby boomers retiring into Social Security and Medicare, rising health care costs, and debt interest expenses. You can't simply cancel those costs. Nor can you more aggressively eviscerate popular programs just to honor a pledge to spare millionaires, billionaires, and corporations from one dollar in new taxes. Everyone must contribute. The most ambitious-yet-plausible conservative reforms would limit long-term spending to 23 percent of GDP, which in turn requires revenues of 20 percent to stabilize the debt. This means ambitious reforms to Social Security, Medicare, and defense, as well as new taxes. Every year of delay leaves the debt larger, interest costs higher, and aging boomers less able to absorb reforms—forcing a more tax-heavy eventual solution. Seek a compromise now, not later.

Here's the painful reality for Democrats: You cannot chase spending heading to 32 percent of GDP with taxes. Even maximizing every tax-the-rich policy is not close to enough. Nor could deep military cuts or Medicare for All make a major dent in deficits heading toward 14 percent of GDP. Furthermore, middle-class families will not accept their taxes doubling merely to ensure that wealthier baby boomer retirees can continue to collect Social Security and Medicare benefits far exceeding their lifetime contributions. Nor is it "progressive" to squeeze every remaining progressive funding priority and soak up all plausible upper-income taxes simply to subsidize often-wealthy seniors.

And the reality for both parties: You need each other. You need to put all spending and taxes on the table to achieve the required savings, and you need each other to provide the necessary political cover. No party is strong enough to muscle through a partisan, one-sided austerity solution and then survive the brutal partisan onslaught that follows. The political model is the 1983 Social Security reforms, where both parties held hands, jumped together, and were overwhelmingly reelected.

The most important reform variable is the voters. Lawmakers will not act as long as they fear that even discussing deficit-reduction proposals will provoke a furious backlash. For decades, we've been warned that a debt crisis is coming after the boomers retire. With budget deficits exceeding $2 trillion and likely surging past $3 trillion within a decade, does anyone care to stop it?

The post Why Did Americans Stop Caring About the National Debt? appeared first on Reason.com.