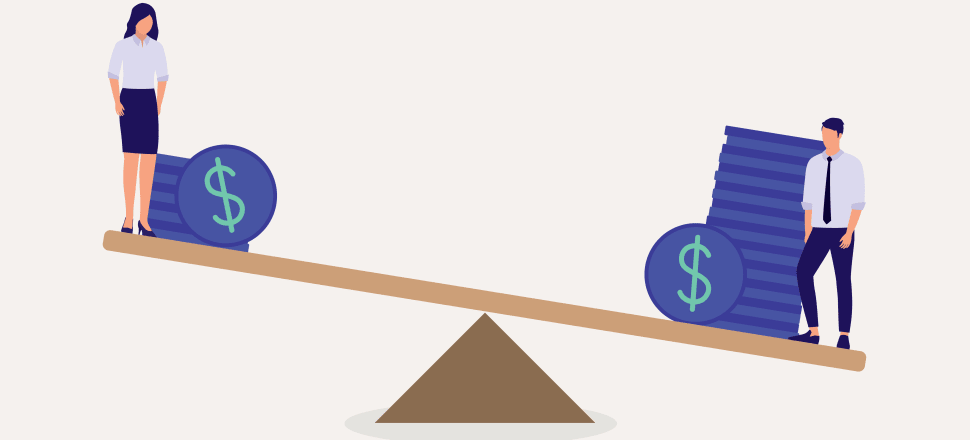

On the 50th anniversary of the Equal Pay Act, we need to not merely prohibit but instead prevent discrimination in pay on the basis of sex, ethnicity or disability

Opinion: Introduced 50 years ago this past week, the Equal Pay Act 1972 was meant to prohibit discrimination in pay on the basis of sex, ethnicity or disability. It is depressing to find little progress has been made and large numbers of people are still paid inequitably.

The gender pay gap in Aotearoa New Zealand – how much less women are paid than men – is 9.2 percent, according to Manatū Wāhine Ministry for Women.

But the intersection of gender and ethnicity generates even more substantial pay gaps, disproportionately affecting Māori, Pacific, Asian and ethnic minority communities. The same greater gaps apply to people with disabilities.

The gap between the average hourly earnings of a European male worker and Pacific female worker is 27 percent. What this means, in real earning terms, is that in effect from 1 October Pacific women began working for free.

Research this year showed men on average still earn 10 percent more than women in New Zealand. Statistics NZ’s data show the average hourly wage earned by Māori employees was 82 percent of the average hourly Pākehā wage, while the average wage earned by Pacific employees was 77 percent of the average Pākehā wage.

Women comprise nearly 72 percent of the part-time workforce and 48 percent of the full-time workforce in New Zealand, but women’s work tends to be low paid, and women are under-represented in higher-level jobs.

Pay gaps have a continuing impact throughout people’s working lives, including on their retirement savings.

Women’s comparatively smaller accumulations of retirement savings, the gender pension gap, is seldom measured or even acknowledged. But women are up to $318,000 worse off in retirement by the time they are at the end of their working life.

This is despite the fact New Zealand women are comparatively fortunate: the tier 1 state pension, New Zealand Superannuation (NZS), is individual, inclusive, and non-contributory, so is gender-blind. At 65, if a person has been resident in New Zealand for 10 years since the age of 20, with five of those years since the age of 50, they qualify for NZS, whether they have ever been employed or paid tax. And NZS is not means-tested, and is taxed as part of total income, so there is no disincentive to continue employment.

However, it is a different story when it comes to KiwiSaver. Women who are able to contribute can of course take advantage of KiwiSaver’s attractive features including the Government’s annual contribution of $521 providing the saver meets a minimum savings contribution of $1,043 level.

But women’s lower earnings make it less likely they can afford to contribute. And lower earnings plus smaller savings pots also make women more risk-averse, so their savings, when they have them, grow more slowly.

On the 50th anniversary of the Equal Pay Act, we need to not merely prohibit but instead prevent discrimination in pay on the basis of sex, ethnicity or disability.

The Government needs to make it compulsory for businesses to report their pay gaps, and make that report available for public scrutiny. That scrutiny will encourage businesses to remove their gender and ethnic biases and to be more equitable.